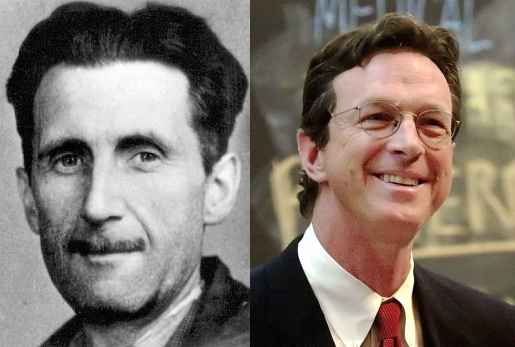

Images via Wikimedia Commons

In his 2002 memoir, Travels, Michael Crichton took his readers back several decades, to the early 1960s when, as a Harvard student, he tried an interesting little experiment in his English class. He recalled:

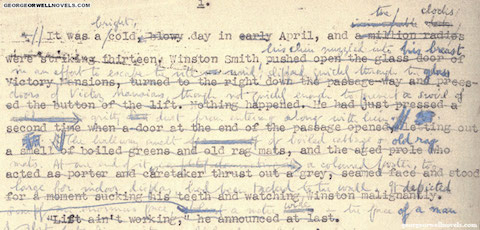

I had gone to college planning to become a writer, but early on a scientific tendency appeared. In the English department at Harvard, my writing style was severely criticized and I was receiving grades of C or C+ on my papers. At eighteen, I was vain about my writing and felt it was Harvard, and not I, that was in error, so I decided to make an experiment. The next assignment was a paper on Gulliver’s Travels, and I remembered an essay by George Orwell that might fit. With some hesitation, I retyped Orwell’s essay and submitted it as my own. I hesitated because if I were caught for plagiarism I would be expelled; but I was pretty sure that my instructor was not only wrong about writing styles, but poorly read as well. In any case, George Orwell got a B- at Harvard, which convinced me that the English department was too difficult for me.

I decided to study anthropology instead. But I doubted my desire to continue as a graduate student in anthropology, so I began taking premed courses, just in case.

Most likely Crichton submitted Orwell’s essay 1946 essay, “Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver’s Travels.” He eventually went to Harvard Medical School but kept writing on the side. Perhaps getting a grade just a shade below Orwell’s B- gave Crichton some bizarre confirmation that he could one day make it as a writer.

Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. And if you want to make sure that our posts definitely appear in your Facebook newsfeed, just follow these simple steps.

Looking for free, professionally-read audio books from Audible.com, including works by Crichton and Orwell? Here’s a great, no-strings-attached deal. If you start a 30 day free trial with Audible.com, you can download two free audio books of your choice. Get more details on the offer here.

via Reddit

Related Content:

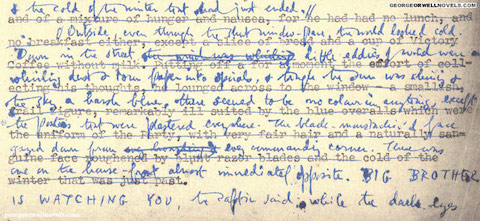

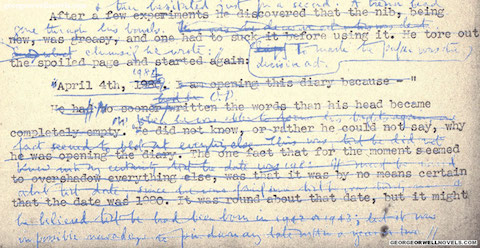

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

George Orwell’s Harrowing Race to Finish 1984 Before His Death