While the world retreated indoors in March, and the cinemas we knew and loved closed up shop, so many film libraries have turned around and opened up their archives to the world. This is a good thing. Don’t say you have nothing to watch! We have explored all the links below and can verify that they are all indeed free to watch. Some are even free to download. Here’s a brief rundown of some we’ve found:

The National Film Registry of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress annually selects films to preserve that it considers “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” and quite a lot of them are available to screen. May we suggest:

Modesta, Benjamin Doniger’s 1955 short drama about women’s rights in a rapidly modernizing Puerto Rico. It won the prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1956.

St. Louis Blues, basically an extended music video (before such a thing existed) for the Queen of the Blues, Bessie Smith, from 1929.

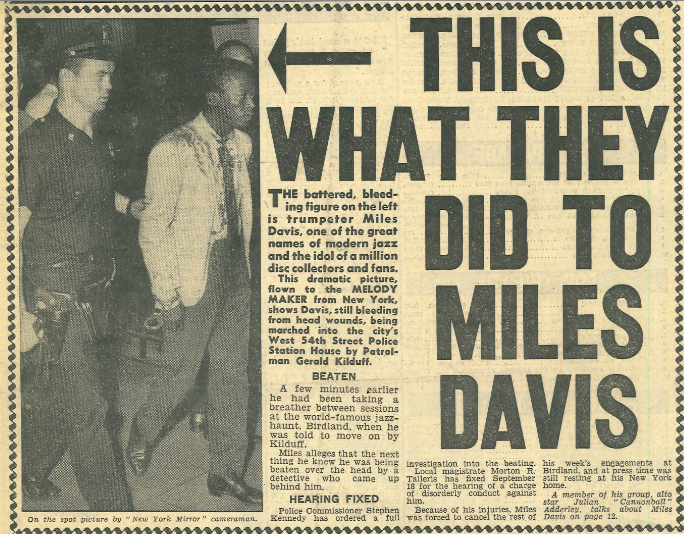

Within Our Gates, the astounding 1919 feature film by Oscar Micheaux. Directed by and starring African-Americans, this rebuttal to Birth of a Nation says something more incisive about American racial politics than most films created in the 20th century.

Cinematheque Francaise

The physical Cinematheque–a cultural institution since 1936, and currently housed in a Frank Gehry-designed building–might be closed, but its streaming platform, dubbed “Henri” is up and showing some rare and restored classics. On one hand, it really helps if you can understand French, because not everything is subtitled. On the other, there are plenty of silent and subbed films:

Protea, Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset’s 1913 response to the Fantomas serials, features Josette Andriot as the slinky, sexy Mata Hari-like super-spy, a few years before Irma Vep and her similar get-up.

The Fall of the House of Usher: Jean Epstein’s surreal adaptation of the Poe classic features brilliant photography and an expressionist style. Fans of The Lighthouse will appreciate its lunacy.

Paris qui dort: Rene Clair’s *other* surreal film made in 1924 (the better known is Entr’acte), this glorious 4K restoration looks like it was shot yesterday as a group of friends wake up to find that all people in Paris have been frozen in place. Play time commences and there is some footage of climbing the Eiffel Tower that might give you the willies. Watch it above.

Japanese Animated Film Classics

With works that go back as far as 1917, this is a deep dive into the world of Japanese animation curated by the Nobuo Ofuji Memorial Museum. There’s traditional cell animation, but also a surprising amount of cut-out animation

The Dull Sword, Junichi Kuichi’s short film from 1917, is a tale of a hapless samurai with an ending told in shadow puppets.

Propagate is a 1935 film from Shigeji Ogino, showing the cycle of plant life through a modernist dance of black and white shapes, close to Oskar Fischinger in style.

Ari-chan the Ant is more what we expect from animation in 1941–a copy of the Disney/Merrie Melodies house style, pleasant enough, but under Mitsuyo Seo’s direction also a critique of imperialism, however subtle. Seo would go on to direct Japan’s first feature-length animated film, Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors.

National Film Preservation Foundation

Bringing us full circle, the NFPF is a non-profit created by Congress in 1997 to save films that otherwise would disappear, and that includes many early animated films, avant-garde works, and films that were once thought lost but have since been discovered in Australia and New Zealand, around 2,500 works.

Too Much Johnson is the long-thought-destroyed film directed by Orson Welles that was to be part of his 1938 multimedia production for his Mercury Theater. The archive presents both the 66 minute work print and a 34 minute reimagined cut.

The Fall of the House of Usher…wait, didn’t we already mention this? In fact, just like the year that brought us Armageddon and Deep Impact, another Poe adaptation hit the screens in 1928. This one is shorter, and even more surreal, and directed by James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber.

At first this silent footage of the Negro Leagues seems a bit too comical–a baseball version of the Harlem Globetrotters–but it’s actually a portrait of an era in flux, two years before segregation was about to end in baseball. Shot at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, the star of this footage is Reece “Goose” Tatum of the Cincinnati Clowns. As the film notes point out, just because they were goofing off for the camera doesn’t mean these players weren’t athletes–Hank Aaron was their shortstop before signing to the Braves, and the Clowns’ rival team, the Kansas City Monarchs, boasted Jackie Robinson also as a shortstop.

You can find more free films in the Relateds below…

Related Content:

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

60 Free Film Noir Movies

Watch 3,000+ Films Free Online from the National Film Board of Canada

Watch More Than 400 Classic Korean Films Free Online Thanks to the Korean Film Archive

Download 6600 Free Films from The Prelinger Archives and Use Them However You Like

1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.