From the album that launched a million bands to possibly the worst rap song of all time—from perfect, career-reviving collaborations to abysmal career-killing ones—Lou Reed’s rock and roll run has seen its share of highs and rock-bottom lows. Reed warrants comparison with Neil Young for his longevity, hit-and-miss prolific output, and gadfly ability to flit from project to project, sound to sound, while still sounding distinctively himself. And like Young, there are too many phases, too many albums, great and terrible, to really do the life’s work justice in any one retrospective.

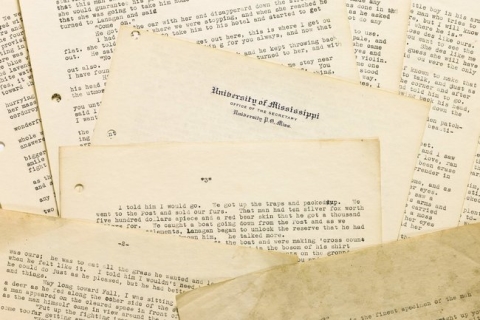

But the 1998 documentary above, from the PBS American Master’s series, makes an admirable attempt. Called Rock and Roll Heart after Reed’s 1976 album and single of the same name, the film lets Reed tell much of his own story: his teenage years as a devotee of 50s rock and doo wop, his college-days association with poet Delmore Schwartz, episodes in his life that very much came to define his art, which marries a finely-tuned literary sensibility to the simplicity and tunefulness of classic rock and roll. Reed’s warped, lyrical takes on streetlife psychodrama and his love for drone notes and feedback, however, took rock songwriting places it had never been before. At the opening of the film, Reed delivers an epigrammatic gem about himself: “I disliked groups, disliked authority. Uh… I was made for rock and roll.”

Reed’s dislike of groups translates throughout his career into a reputation for difficulty that sent collaborators running from him, either because he fired them (as he most famously did to the brilliant John Cale) or because they’d had enough of his egotism. Nonetheless, many of those same people—Cale included—came back to work with Reed again. Cale shows up above, telling stories of the genesis of The Velvet Underground—of him and Reed playing “Waiting for the Man” and “Heroin” on a Harlem streetcorner on viola and acoustic guitar. Other confreres of Reed’s genius also appear in interviews: Velvet’s drummer Maureen Tucker, David Bowie, Patti Smith, Jim Carroll, Philip Glass, and of course the man Reed credits most for his success, Andy Warhol, in archival footage from 1966.

The love/hate pairing of The Velvets and Nico gets an airing, and there’s loads of film of Lou performing, but at 73 minutes, Rock and Roll Heart feels a little thin, and its tone is almost entirely celebratory, eliding the musical low points (like the stab at rap) and ending with Reed’s forays into theater with Time Rocker. But these are forgivable flaws. There’s no way to cover all the ground Reed’s broken (he’s released an album roughly every year since 1972). And at 71 (if he can recover from that Metallica mash-up), he’s still at it—as he says in an interview above, until he dies.

Related Content:

Philip Glass & Lou Reed at Occupy Lincoln Center: An Artful View

Andy Warhol Quits Painting, Manages The Velvet Underground (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness