Updated on December 24, 2013: Yesterday the British government brought a sad chapter to a close when it finally issued a posthumous pardon to Alan Turing, who was convicted in 1952 of breaking laws that criminalized homosexuality. The post you see below was originally written in February, 2012, when the question of Turing being pardoned was still up for debate. The film featured above is still very much worth your while.

This week the British government finally pardoned Alan Turing. One of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, Turing laid the foundations for computer science and played a key role in breaking the Nazi Enigma code during World War II. In 1952 he was convicted of homosexuality. He killed himself two years later, after being chemically castrated by the government.

On Monday, Justice Minister Tom McNally told the House of Lords that the government of Prime Minister David Cameron stood by the decision of earlier governments to deny a pardon, noting that the previous prime minister, Gordon Brown, had already issued an “unequivocal posthumous apology” to Turing. McNally was quoted in the Guardian:

A posthumous pardon was not considered appropriate as Alan Turing was properly convicted of what at the time was a criminal offense. He would have known that his offense was against the law and that he would be prosecuted. It is tragic that Alan Turing was convicted of an offense which now seems both cruel and absurd–particularly poignant given his outstanding contribution to the war effort. However, the law at the time required a prosecution and, as such, long-standing policy has been to accept that such convictions took place and, rather than trying to alter the historical context and to put right what cannot be put right, ensure instead that we never again return to those times.

The decision came as a disappointment to thousands of people around the world who had petitioned for a formal pardon during the centenary year of Turing’s birth. The Guardian also quoted an email sent by American mathematician Dennis Hejhal to a British colleague:

i see that the House of Lords rejected the pardon Feb 6 on what are formal grounds.

if law is X on date D, and you knowingly break law X on date D, then you cannot be pardoned (no matter how wrong or flawed law X is).

the real reason is OBVIOUS. they do not want thousands of old men saying pardon us too.

Efforts to obtain a pardon for Turing are continuing. British citizens and UK residents can still sign the petition.

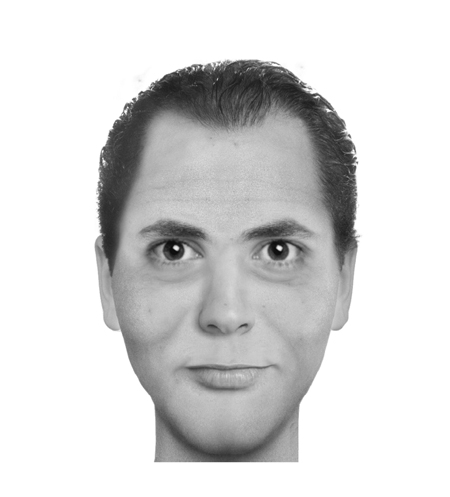

To learn more about Turing’s life, you can watch the 1996 BBC film Breaking the Code (above, in its entirety), featuring Derek Jacobi as Turing and Nobel Prize-winning playwright Harold Pinter as the mysterious “Man from the Ministry.” Directed by Herbert Wise, the film is based on a 1986 play by Hugh Whitemore, which in turn was based on Andrew Hodge’s 1983 book Alan Turing: The Enigma.

Breaking the Code moves back and forth between two time frames and two very different codes: one military, the other social. The film runs 91 minutes, and has been added to our collection of Free Movies Online.