It’s fair to say that every period which has celebrated the literature of antiquity has held epic Roman poet Virgil in extremely high regard, and that was never more the case than during the early Christian and medieval eras. Born in 70 B.C.—writes Clyde Pharr in the introduction to his scholarly Latin text—“Vergil was ardently admired even in his own day, and his fame continued to increase with the passing centuries. Under the later Roman Empire the reverence for his works reached the point where the Sortes Virgilianae came into vogue; that is, the Aeneid was opened at random, and the first line on which the eyes fell was taken as an omen of good or evil.”

This cult of Virgil only grew until “a great circle of legends and stories of miracles gathered around his name, and the Vergil of history was transformed into the Vergil of magic.” The spelling of his name also transformed from Vergil to Virgil, “thus associating the great poet with the magic or prophetic wand, virgo.” Pharr quotes from J.S. Tunison’s Master Virgil, a study of the poet “as he seemed in the Middle Ages”:

The medieval world looked upon him as a poet of prophetic insight, who contained within himself all the potentialities of wisdom. He was called the Poet, as if no other existed; the Roman, as if the ideal of the commonwealth were embodied in him; the Perfect in Style, with whom no other writer could be compared; the Philosopher, who grasped the ideas of all things…

Virgil, after all, acted as the wise guide through the Inferno for late medieval poet Dante, who was accorded a similar degree of reverence in the early modern period.

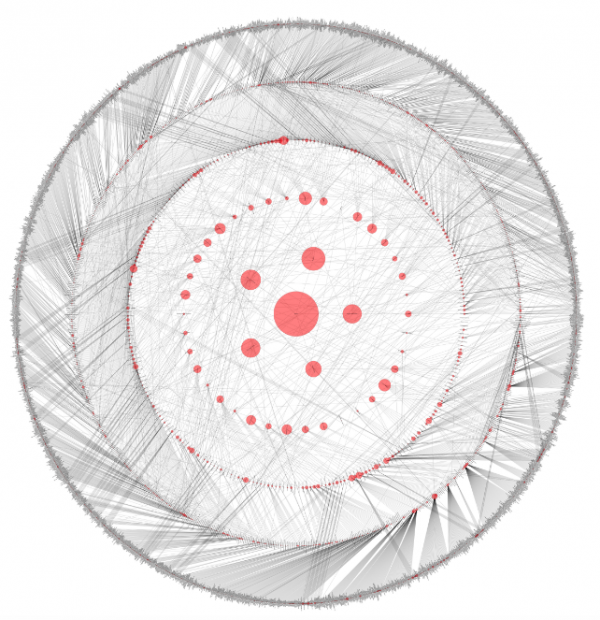

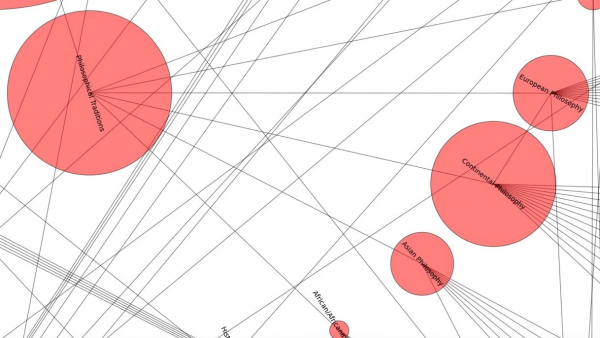

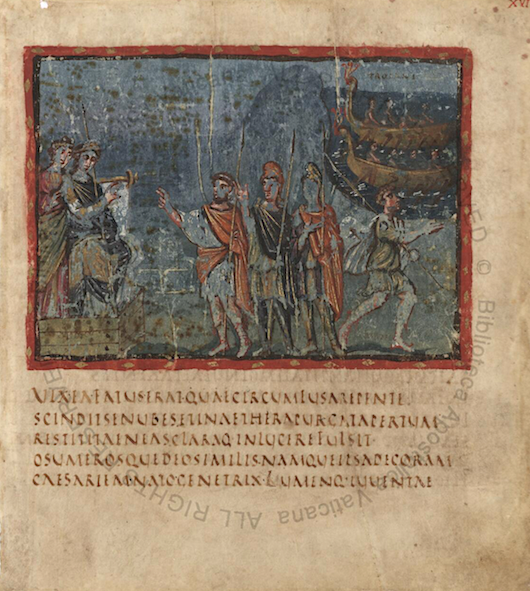

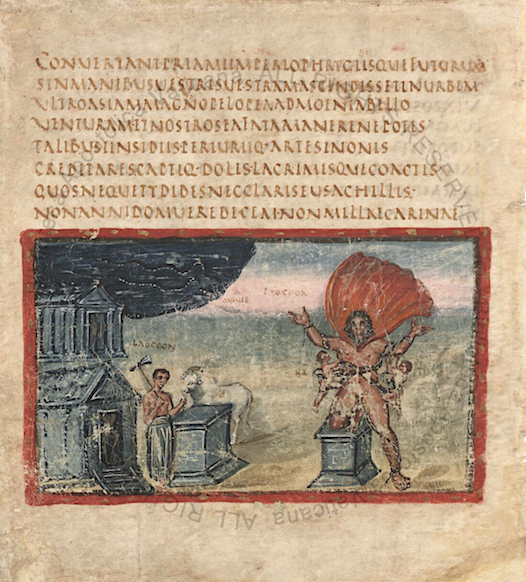

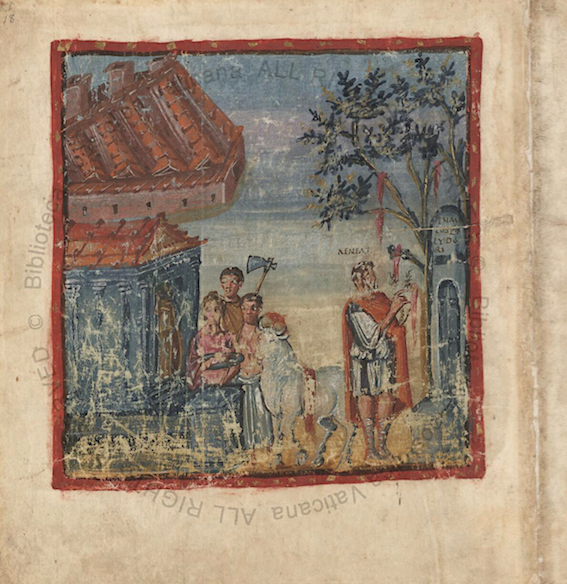

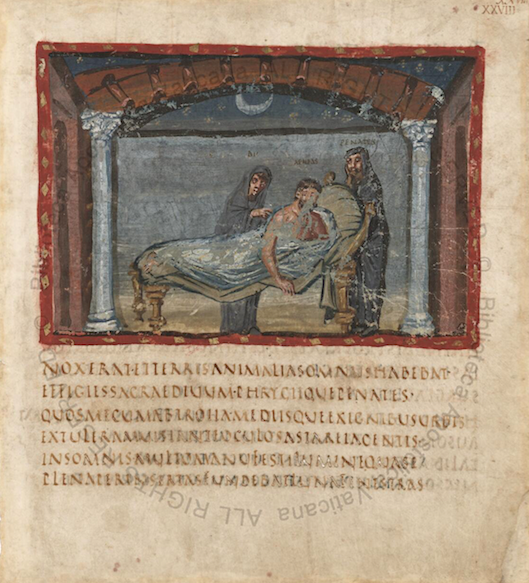

We should keep the cult of Virgil, and of his epic poem The Aeneid, in mind as we survey the text you see represented here—an illuminated manuscript from Rome created sometime around the year 400 (view the full, digitized manuscript here). Beginning at the end of another great epic—The Iliad—Virgil’s long poem connects the world of Homer to his own through Aeneas and his companions, Trojan refugees and mythical founders of Rome. It is somewhat ironic that the Christian world came to venerate the poem for centuries—claiming that Virgil predicted the birth of Christ—since the Roman poet’s purpose, writes Pharr, was “to see effected… a revival of faith in the old-time religion”—the old-time pagan religion, that is.

But the careful preservation of this ancient manuscript, some 1,600 years old, testifies to the Catholic church’s profound respect for Virgil. “Known as the Vergilius Vaticanus,” writes Hyperallergic, it’s one of the world’s oldest versions of the Latin epic poem, and you can browse it for free online” at Digita Vatica, a nonprofit affiliated with the Vatican Library.

Written by a single master scribe in rustic capitals, an ancient Roman calligraphic script, and illustrated by three different painters, Vergilius Vaticanus is one of only three illuminated manuscripts of classic literature. Granulated gold, applied with a brush, highlights meticulously colored images of famous scenes from the poem: Creusa as she tries to keep her husband Aeneas from going into battle; the islands of the Cyclades and the city of Pergamea destroyed by pestilence and drought; Dido on her funeral pyre, speaking her final soliloquy.

Hyperallergic describes the painstaking care a Tokyo-based firm took in digitizing the fragile text. Digita Vaticana is currently in the midst of scanning its entire collection of 80,000 delicate, ancient manuscripts, a process expected to take 15 years and cost 50 million euros.

Should you wish to contribute to the effort, you can make a donation to the project. The first 200 donors willing and able to fork over at least 500 euros (currently about $533), will receive a printed reproduction of the Vergilius Vaticanus, sure to impress the classics lovers in your life. Should you wish to read the Aeneid in its original language, a true undertaking of love, you can’t go wrong with Pharr’s excellent scholarly text of the first six books (or see an online Latin text here). If you’d rather skip the genuinely difficult and laborious translation, you can always read John Dryden’s translation free online.

You can visit the illuminated manuscript online here.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Manuscript of Beowulf Digitized and Now Online

Hear Homer’s Iliad Read in the Original Ancient Greek

Learn Latin, Old English, Sanskrit, Classical Greek & Other Ancient Languages in 10 Lessons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness