On the strength of its hit single Enter Sandman, Metallica’s eponymous 1991 album eventually went platinum, and the band became one of the biggest heavy metal acts around. Since then, the influence of “Enter Sandman” has rippled out into the larger culture. Since 1999, Mariano Rivera, surely the greatest relief pitcher in the history of baseball, has ritually made his entrance to the game with “Enter Sandman” providing the soundtrack. (Perhaps a strange pick for a mild-mannered, deeply religious man. But somehow it works.) And the song has been covered umpteen times — by other metal bands (most notably Motörhead) but also by Weird Al Yankovic, Pat Boone, and the bluegrass band called Iron Horse.

Formed over a decade ago in the recording capital of Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Iron Horse features Tony Robertson on mandolin, Vance Henry on guitar, Ricky Rogers on bass, and Anthony Richardson on banjo. And, together, they’ve taken some risks along the way.

In 2003, they released Fade to Bluegrass: Tribute to Metallica, a collection of ten Metallica songs done in bluegrass fashion — “or at least as bluegrass as it’s possible for Metallica songs to be.” Speaking about the album on their website, they write:

Metallica’s thundering drums, heart-pounding guitars and anguished vocals tell the story of people lost in the hustle of modern society. Bluegrass music sings the tale of people stuck between heaven and hell, the farm and the city and love and hate. In many ways Metallica and bluegrass are brothers, one raised in the urban jungle and the other in the country. So what happens when these two estranged siblings get together? Fade to Bluegrass: Tribute to Metallica has the answer. Banjo and mandolin replace electric guitars and high lonesome harmonies soar in place of growling vocals to create a surprising and moving tribute. Performed with passion and skill by Alabama bluegrass band Iron Horse, and featuring classics such as “Unforgiven,” “Enter Sandman” and “Fade to Black,” Fade to Bluegrass: Tribute to Metallica is a family reunion between brothers heavy metal and bluegrass.

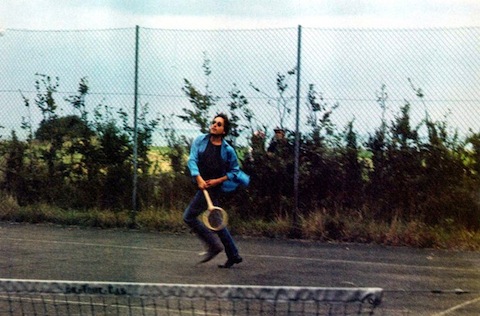

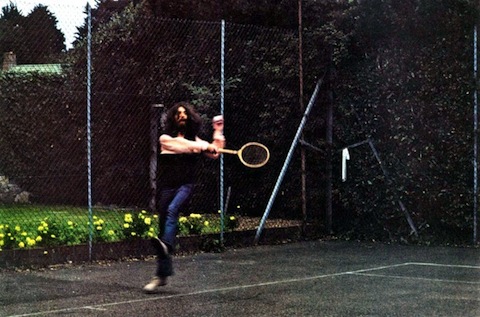

You can watch Iron Horse perform “Enter Sandman” above. And below you can see that Metallica’s lead guitarist Kirk Hammett approves:

via Devour

Related Content:

Steve Martin on the Legendary Bluegrass Musician Earl Scruggs

Pickin’ & Trimmin’ in a Down-Home North Carolina Barbershop: Award-Winning Short Film

Steve Martin Writes Song for Hymn-Deprived Atheists