After the waning of abstract expressionism, Robert Rauschenberg’s exuberant prints, paintings, sculptures, and three-dimensional collages he called “Combines” rejuvenated the New York art world and helped bring pop art to prominence, anticipating Warhol’s experiments. And now students of twentieth-century American art can connect with all of the artist’s work in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection without setting foot in the Bay area, thanks to SFMOMA’s Rauschenberg Research Project, which allows users to download high res images of the museum’s Rauschenbergs. Research materials—including commentary, interviews, essays, and more—accompany each image. Clicking on the main link for each image will send you to a page with a lengthy description. Scrolling down to the bottom of the page, you’ll find individual links for each of the associated files and an omnibus link for all of them at once.

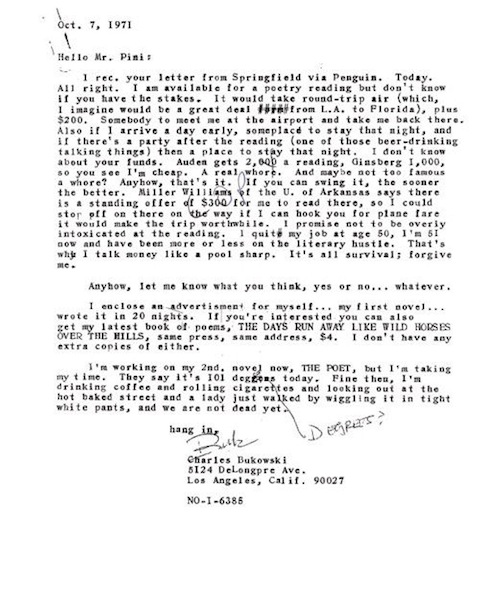

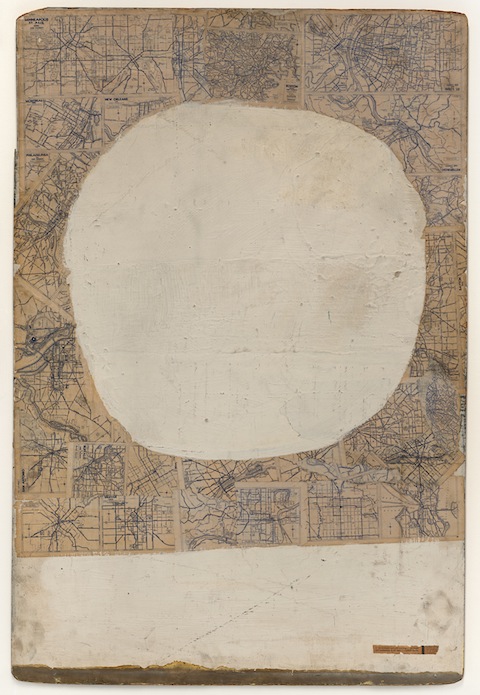

It’s certainly not a substitute for seeing the work up close in all its ontological materiality, but it’s still quite a wonderful resource for researchers, art historians, and even general enthusiasts of Rauschenberg, particularly since many of the works in SFMOMA’s database are not currently on display (and the museum is temporarily closed during an expansion). A painting you can’t see in person is the dense collage Mother of God (at top), one of Rauschenberg’s earliest surviving paintings from a period in the 50s when the artist explored several religious themes. The painting’s brown background is composed of layers of maps of American locales, and the site allows you to zoom in and examine each one in fine detail. In the video above—one of the digital project’s collection of artifacts—see Rauschenberg discuss the painting with curator Walter Hopps and SFMOMA Director David A. Ross in a 1999 interview.

via Metafilter

Related Content:

Rauschenberg Erases De Kooning

The Rijksmuseum Puts 125,000 Dutch Masterpieces Online, and Lets You Remix Its Art

LA County Museum Makes 20,000 Artistic Images Available for Free Download

The National Gallery Makes 25,000 Images of Artwork Freely Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness