Hearing someone discuss the nature of art can easily grow tiresome — indeed, it has, as a subject, become something of a shorthand for the tiresome. But Marcel Duchamp, the French painter, sculptor, conceptual artist, and chess enthusiast, could do it right. He did it by getting straight to the point, a succinctness most famously demonstrated in Fountain, the simple, everyday porcelain urinal he signed and submitted as a work of art for display. The fact that the art world soon put Fountain (and its similar, mass-produced descendants) quite literally on a pedestal makes an observation about art more cleanly than thousands of words on the role of the artist in modern society ever could.

But where–whether you paint on a canvas, chisel into a block of stone, or make a purchase at the plumbing store down the street–does this impulse to make art come from? Do artists consciously create their work, acting out creative decisions made within, or do they merely give form to artistic impulses received from… elsewhere? And what do we talk about when we talk about the work of art the artist ultimately produces?

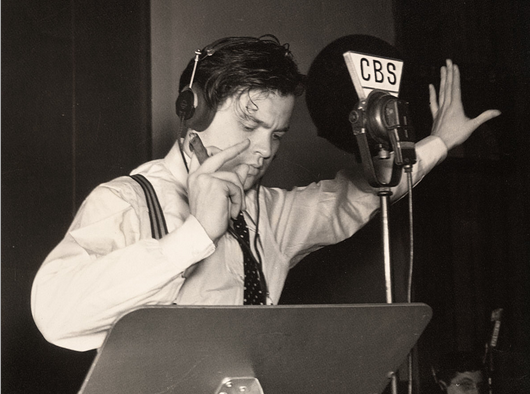

Duchamp, concise as ever, addressed the issue in 1957 when he gave the eight-minute lecture “The Creative Act” which you can hear above (or on the full Surrealism Reviewed album available on Spotify below). He identifies one important part of the process as what he calls the “art coefficient.”

“In the creative act,” Duchamp says, “the artist goes from intention to realization through a chain of totally subjective reactions. His struggle toward the realization is a series of efforts, pains, satisfaction, refusals, decisions, which also cannot and must not be fully self-conscious, at least on the aesthetic plane. The result of this struggle is a difference between the intention and its realization, a difference which the artist is not aware of.” This gap between what the artist “intended to realize and did realize,” Duchamp calls the art coefficient, “an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed.”

But none of it matters, in Duchamp’s thinking, unless someone else actually thinks about the work of art. “No work of art — no balloon dog, no poem mentioning cold-water flats, no four-minute-and-thirty-three-second performance by silent musicians — is a great work until posterity says so,” writes the Paris Review’s Rebecca Bates in a post on the lecture (and a “sort-of Dadaist Mad Libs” recently made out of it). She quotes Duchamp in a 1964 interview with Calvin Tomkins: “The artist produces nothing until the onlooker has said, ‘You have produced something marvelous.’ The onlooker has the last word in it.” According to Duchamp’s perceptions, we, as posterity, as the onlookers, have the last word on all work, even Duchamp’s own. So go ahead and yammer a bit about the nature of art; doing so not only keeps the art alive, but made it art in the first place.

Related Content:

Anémic Cinéma: Marcel Duchamp’s Whirling Avant-Garde Film (1926)

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.