I’ve never quite understood why the phrase “revisionist history” became purely pejorative. Of course, it has its Orwellian dark side, but all knowledge has to be revised periodically, as we acquire new information and, ideally, discard old prejudices and narrow frames of reference. A failure to do so seems fundamentally regressive, not only in political terms, but also in terms of how we value accurate, interesting, and engaged scholarship. Such research has recently brought us fascinating stories about previously marginalized people who made significant contributions to scientific discovery, such as NASA’s “human computers,” portrayed in the book Hidden Figures, then dramatized in the film of the same name.

Likewise, the many women who worked at Bletchley Park during World War II—helping to decipher encryptions like the Nazi Enigma Code (out of nearly 10,000 codebreakers, about 75% were women)—have recently been getting their historical due, thanks to “revisionist” researchers. And, as we noted in a recent post, we might not know much, if anything, about film star Hedy Lamarr’s significant contributions to wireless, GPS, and Bluetooth technology were it not for the work of historians like Richard Rhodes. These few examples, among many, show us a fuller, more accurate, and more interesting view of the history of science and technology, and they inspire women and girls who want to enter the field, yet have grown up with few role models to encourage them.

We can add to the pantheon of great women in science the name Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace, the daughter of Romantic poet Lord Byron. Lovelace has been renowned, as Hank Green tells us in the video at the top of the post, for writing the first computer program, “despite living a century before the invention of the modern computer.” This picture of Lovelace has been a controversial one. “Historians disagree,” writes prodigious mathematician Stephen Wolfram. “To some she is a great hero in the history of computing; to others an overestimated minor figure.”

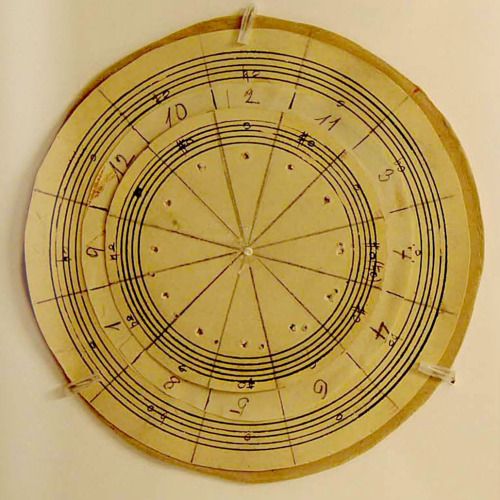

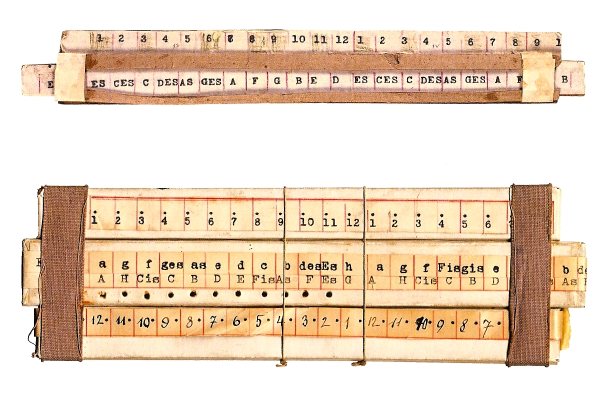

Wolfram spent some time with “many original documents” to untangle the mystery. “I feel like I’ve finally gotten to know Ada Lovelace,” he writes, “and gotten a grasp on her story. In some ways it’s an ennobling and inspiring story; in some ways it’s frustrating and tragic.” Educated in math and music by her mother, Anne Isabelle Milbanke, Lovelace became acquainted with mathematics professor Charles Babbage, the inventor of a calculating machine called the Difference Engine, “a 2‑foot-high hand-cranked contraption with 2000 brass parts.” Babbage encouraged her to pursue her interests in mathematics, and she did so throughout her life.

Widely acknowledged as one of the forefathers of computing, Babbage eventually corresponded with Lovelace on the creation of another machine, the Analytical Engine, which “supported a whole list of possible kinds of operations, that could in effect be done in arbitrarily programmed sequence.” When, in 1842, Italian mathematician Louis Menebrea published a paper in French on the Analytical Engine, “Babbage enlisted Ada as translator,” notes the San Diego Supercomputer Center’s Women in Science project. “During a nine-month period in 1842–43, she worked feverishly on the article and a set of Notes she appended to it. These are the source of her enduring fame.” (You can read her translation and notes here.)

In the course of his research, Wolfram pored over Babbage and Lovelace’s correspondence about the translation, which reads “a lot like emails about a project might today, apart from being in Victorian English.” Although she built on Babbage and Menebrea’s work, “She was clearly in charge” of successfully extrapolating the possibilities of the Analytical Engine, but she felt “she was first and foremost explaining Babbage’s work, so wanted to check things with him.” Her additions to the work were very well-received—Michael Faraday called her “the rising star of Science”—and when her notes were published, Babbage wrote, “you should have written an original paper.”

Unfortunately, as a woman, “she couldn’t get access to the Royal Society’s library in London,” and her ambitions were derailed by a severe health crisis. Lovelace died of cancer at the age of 37, and for some time, her work sank into semi-obscurity. Though some historians have seen her as simply an expositor of Babbage’s work, Wolfram concludes that it was Ada who had the idea of “what the Analytical Engine should be capable of.” Her notes suggested possibilities Babbage had never dreamed. As the Women in Science project puts it, “She rightly saw [the Analytical Engine] as what we would call a general-purpose computer. It was suited for ‘developping [sic] and tabulating any function whatever… the engine [is] the material expression of any indefinite function of any degree of generality and complexity.’ Her Notes anticipate future developments, including computer-generated music.”

In a recent episode of the BBC’s In Our Time, above, you can hear host Melvyn Bragg discuss Lovelace’s importance with historians and scholars Patricia Fara, Doron Swade, and John Fuegi. And be sure to read Wolfram’s biographical and historical account of Lovelace here.

Related Content:

The Contributions of Women Philosophers Recovered by the New Project Vox Website

Real Women Talk About Their Careers in Science

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness