My introduction to the work of James Newell Osterberg, Jr, better known as Iggy Pop, came in the form of “Risky,” a song from Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Neo Geo album that featured not just singing but spoken word from the Stooges’ lead vocalist and punk icon. On that track, Pop speaks grimly and evocatively in the persona of a protagonist “born in a corporate dungeon where people are cheated of life,” repeatedly invoking the human compulsion to “climb to this point, move on, climb to this point, move on.” Ultimately, he poses the question: “Career, career, acquire, acquire — but what is life without a heart?”

Today, we give you Iggy Pop the storyteller asking what life is with a heart — or rather, one heart too many, unceasingly reminding you of your guilt. He tells the story, of course, of “The Tell-Tale Heart,” originally written by the American master of psychological horror Edgar Allan Poe in 1843.

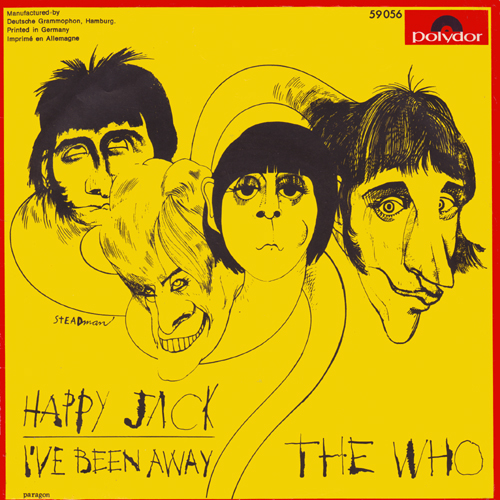

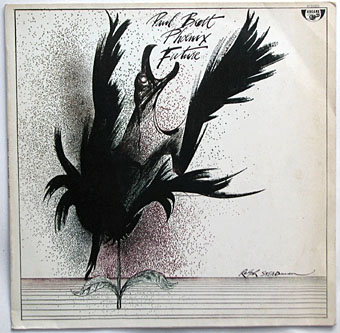

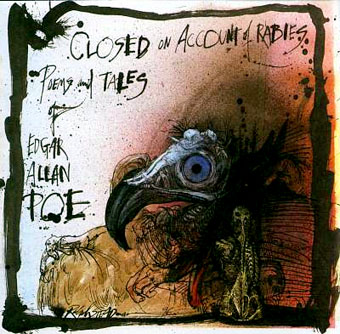

This telling appears on the album Closed on Account of Rabies, which features Poe’s stories as interpreted by the likes of Pop, Christopher Walken, Debbie Harry, Marianne Faithfull and Jeff Buckley. We featured it here on Open Culture a few years back, and more recently included it in our retrospective of album covers by Ralph Steadman.

Here, Pop takes on the role of another narrator consigned to a grim fate, though this one of his own making. As almost all of us know, if only through cultural osmosis, the titular “Tell-Tale Heart,” its beat seemingly emanating from under the floorboards, unceasingly reminds this anxious character of the fact that he has murdered an old man — not out of hatred, not out of greed, but out of simple need stoked, he insists, by the defenseless senior’s “vulture-eye.” For over 150 years, readers have judged the sanity of the narrator of “The Tell-Tale Heart” in any number of ways, but don’t render your own verdict until you’ve heard Iggy Pop deliver the testimony; nobody walks the line between sanity and insanity quite like he does.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Lou Reed Rewrites Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” See Readings by Reed and Willem Dafoe

Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” Read by Christopher Walken, Vincent Price, and Christopher Lee

Watch the 1953 Animation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Narrated by James Mason

Hear a Great Radio Documentary on William S. Burroughs Narrated by Iggy Pop

Edgar Allan Poe Animated: Watch Four Animations of Classic Poe Stories

Download The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe on His Birthday

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for FreeColin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.