Arches on arches! as it were that Rome,

Collecting the chief trophies of her line,

Would build up all her triumphs in one dome,

Her Coliseum stands; the moonbeams shine

As ’twere its natural torches, for divine

Should be the light which streams here, to illume

This long-explored but still exhaustless mine

Of contemplation; and the azure gloom

Of an Italian night, where the deep skies assume

Hues which have words, and speak to ye of heaven,

Floats o’er this vast and wondrous monument,

And shadows forth its glory.

—Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1818)

A modern visitor to Rome, drawn to the Coliseum on a moonlit night, is unlikely to be so bewitched, sandwiched between his or her fellow tourists and an army of vendors aggressively peddling light-up whirligigs, knock off designer scarves, and acrylic columns etched with the Eternal City’s must-see attractions.

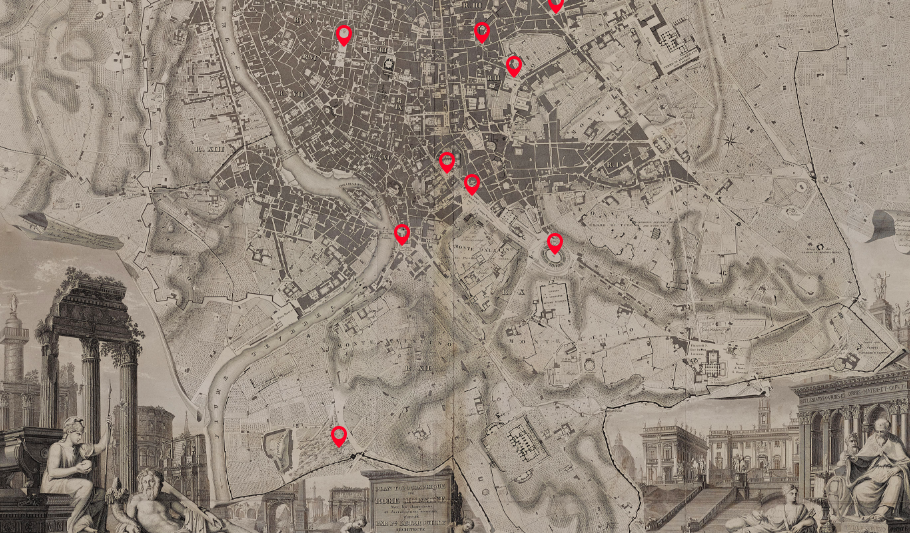

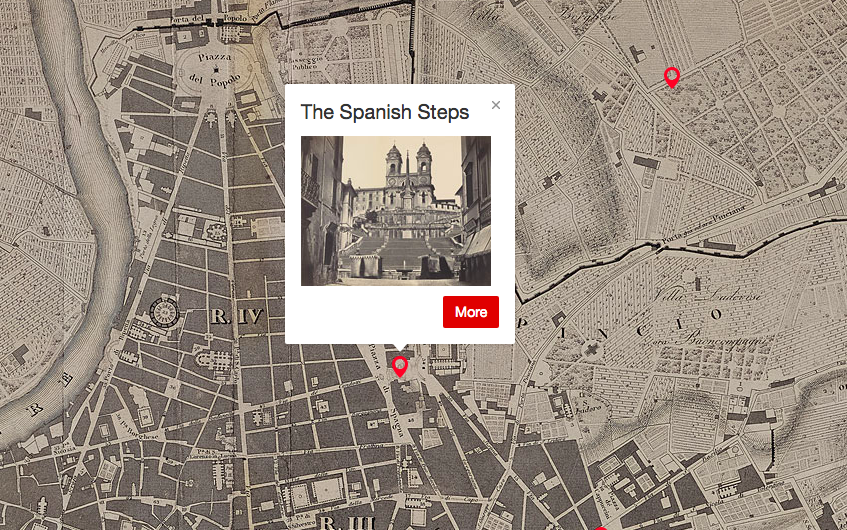

These days, your best bet for touring Rome’s best known landmarks in peace may be an interactive map, compliments of the Morgan Library and Museum. Based on Paul-Marie Letarouilly’s picturesque 1841 city plan, each digital pin can be expanded to reveal descriptions by nineteenth-century authors and side-by-side, then-and-now comparisons of the featured monuments.

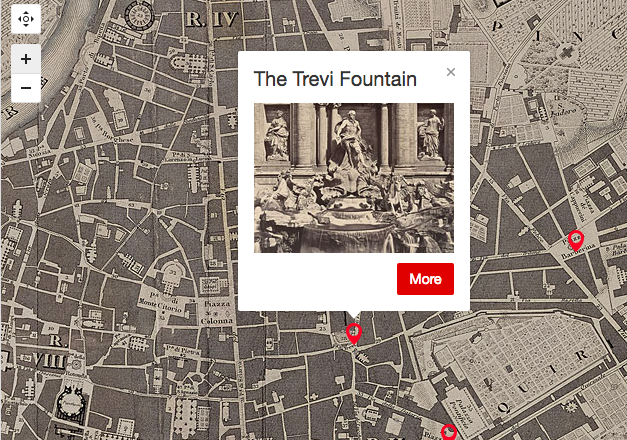

The enduring popularity of the film Three Coins in the Fountain, coupled with the invention of the selfie stick has turned the area around the Trevi Fountain into a pickpocket’s dream and a claustrophobe’s worst nightmare.

Not so in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s day, though unlike Lord Byron, he cultivated a cool remove, at least at first:

They and the rest of the party descended some steps to the water’s brim, and, after a sip or two, stood gazing at the absurd design of the fountain, where some sculptor of Bernini’s school had gone absolutely mad in marble. It was a great palace-front, with niches and many bas-reliefs, out of which looked Agrippa’s legendary virgin, and several of the allegoric sisterhood; while, at the base, appeared Neptune, with his floundering steeds and Tritons blowing their horns about him, and twenty other artificial fantasies, which the calm moonlight soothed into better taste than was native to them. And, after all, it was as magnificent a piece of work as ever human skill contrived. At the foot of the palatial façade was strown, with careful art and ordered irregularity, a broad and broken heap of massive rock, looking as if it might have lain there since the deluge. Over a central precipice fell the water, in a semicircular cascade; and from a hundred crevices, on all sides, snowy jets gushed up, and streams spouted out of the mouths and nostrils of stone monsters, and fell in glistening drops; while other rivulets, that had run wild, came leaping from one rude step to another, over stones that were mossy, slimy, and green with sedge, because in a century of their wild play, Nature had adopted the Fountain of Trevi, with all its elaborate devices, for her own.

The human statues garbed as gladiators and charioteers spend hours in the blazing sun at the foot of the Spanish Steps—the heirs to the artists and models who populated William Wetmore Story’s Roba di Roma:

All day long, these steps are flooded with sunshine in which, stretched at length, or gathered in picturesque groups, models of every age and both sexes bask away the hours when they are free from employment in the studios. … Sometimes a group of artists, passing by, will pause and steadily examine one of these models, turn him about, pose him, point out his defects and excellences, give him a baiocco, and pass on. It is, in fact, a models’ exchange.

The Medici Villa houses the Académie de France, and its gardens remain a pleasant respite, even in 2017. Visitors who aren’t wholly consumed with finding a wifi signal may find themselves fantasizing about a different life, much as Henry James did in his Italian Hours:

Such a dim light as of a fabled, haunted place, such a soft suffusion of tender grey-green tones, such a company of gnarled and twisted little miniature trunks—dwarfs playing with each other at being giants—and such a shower of golden sparkles drifting in from the vivid West! … I should name for my own first wish that one didn’t have to be a Frenchman to come and live and dream and work at the Académie de France. Can there be for a while a happier destiny than that of a young artist conscious of talent and of no errand but to educate, polish and perfect it, transplanted to these sacred shades?…What mornings and afternoons one might spend there, brush in hand, unpreoccupied, untormented, pensioned, satisfied—either persuading one’s self that one would be “doing something” in consequence or not caring if one shouldn’t be.

The interactive map was created to accompany the Morgan’s 2016 exhibition City of the Soul: Rome and the Romantics. Other pitstops include St. Peter’s, the Roman Forum, and The Equestrian Monument of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitol. Begin your explorations here.

Related Content:

Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E.

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.