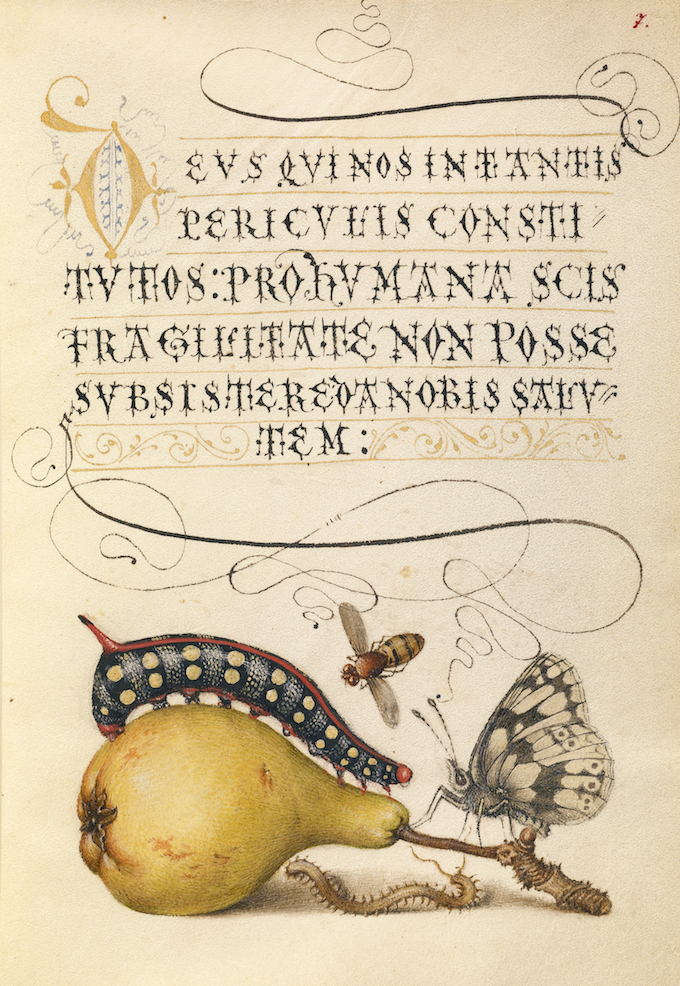

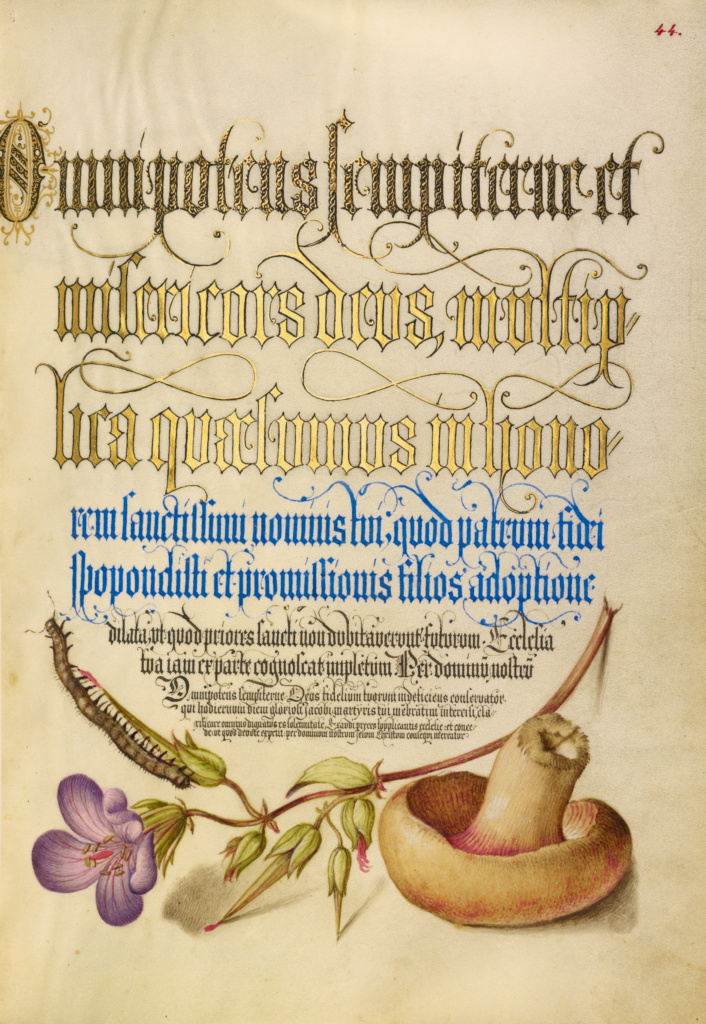

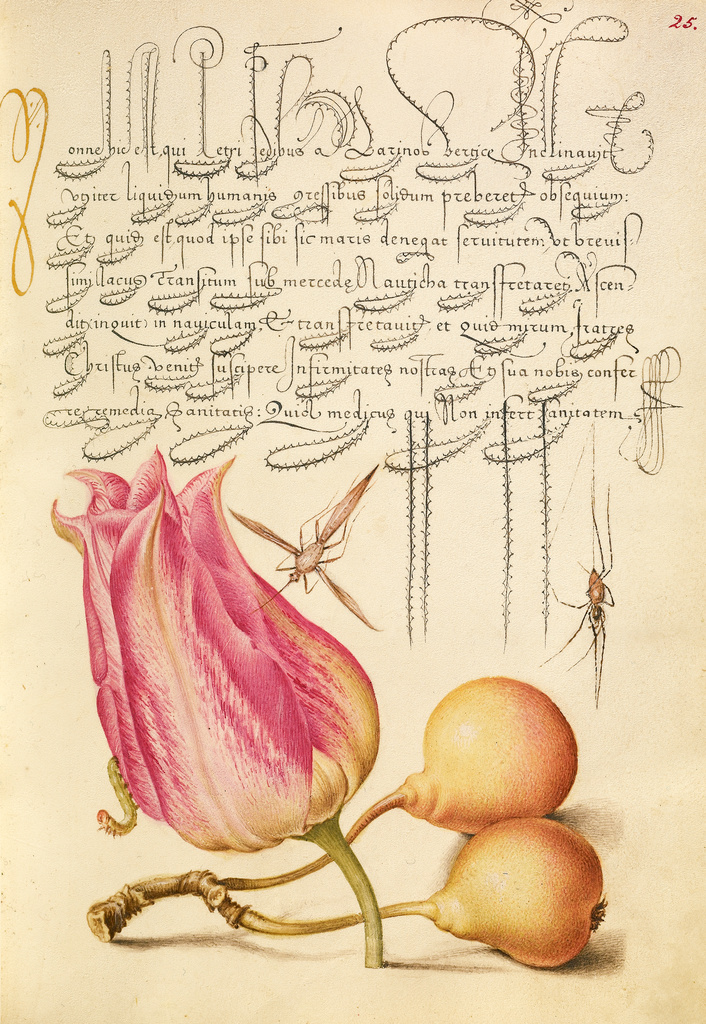

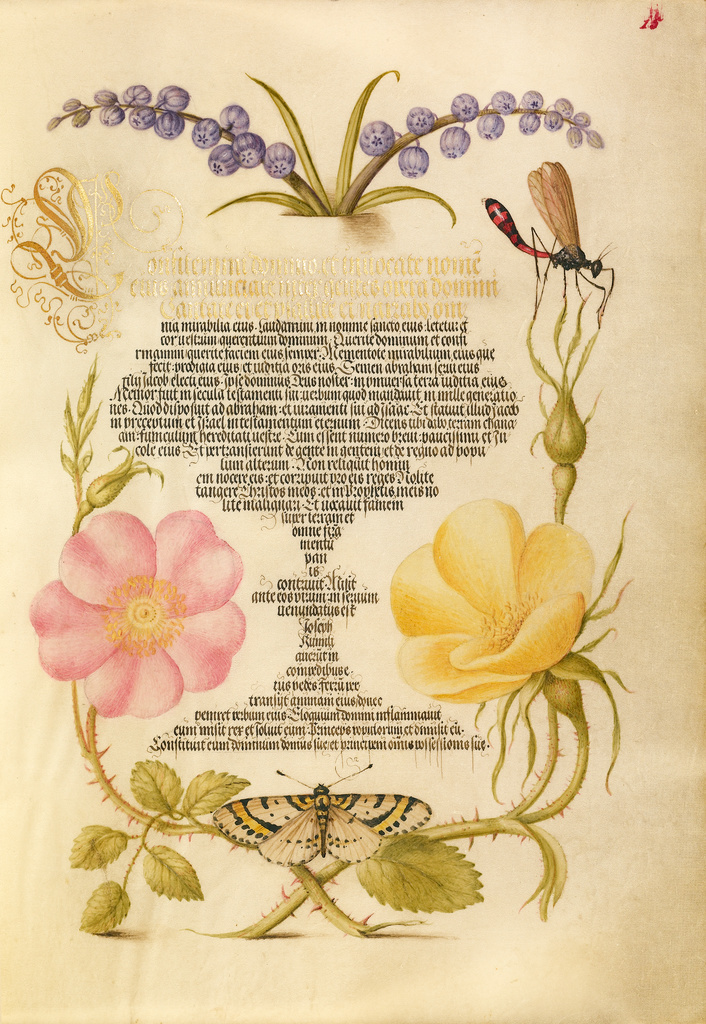

Whenever a technology develops just enough to become interesting, someone inevitably pushes it to extremes. In the case of that reliable and long-lived technology known as the book, writers and artists were looking for ways to maximize its potential as a device for conveying the written word and the drawn image as far back as the 16th century. One particularly glorious example, The Model Book of Calligraphy, has come available online, to view or download, thanks to the Getty. This decades-spanning collaboration shows off not just the artistic writing implied by the title but illustrations whose vividness and detail remain striking even today.

“In the 1500s, as printing became the most common method of producing books, intellectuals increasingly valued the inventiveness of scribes and the aesthetic qualities of writing,” says the Getty’s site.

“From 1561 to 1562, Georg Bocskay, the Croatian-born court secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, created this Model Book of Calligraphy in Vienna to demonstrate his technical mastery of the immense range of writing styles known to him.”

Three decades later, “Emperor Rudolph II, Ferdinand’s grandson, commissioned Joris Hoefnagel” — a Flemish artist well known at the time for his specialization in subjects to do with natural history — “to illuminate Bocskay’s model book. Hoefnagel added fruit, flowers, and insects to nearly every page, composing them so as to enhance the unity and balance of the page’s design. It was one of the most unusual collaborations between scribe and painter in the history of manuscript illumination.”

What we see when we flip through (or zoom in to great levels of digital detail on) The Model Book of Calligraphy’s 184 pages may look like a unified work executed all at once (see them all at the bottom of this page), but it actually combines the sensibilities of not just two creators separated by not just the art forms in which they specialized but more than thirty years of time. Hoefnagel, however, didn’t stay entirely out of the realm of the textual: though most of what he brought to the manuscript takes the form of illuminations, he also added an entirely new section on writing the alphabet. He understood the importance of not just well-crafted pictures and text but their appealing integration, a concept familiar to any designer working in today’s forms of cutting-edge media — as books were four centuries ago. You can purchase print editions that reproduce portions or the entirety of The Model Book of Calligraphy.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.