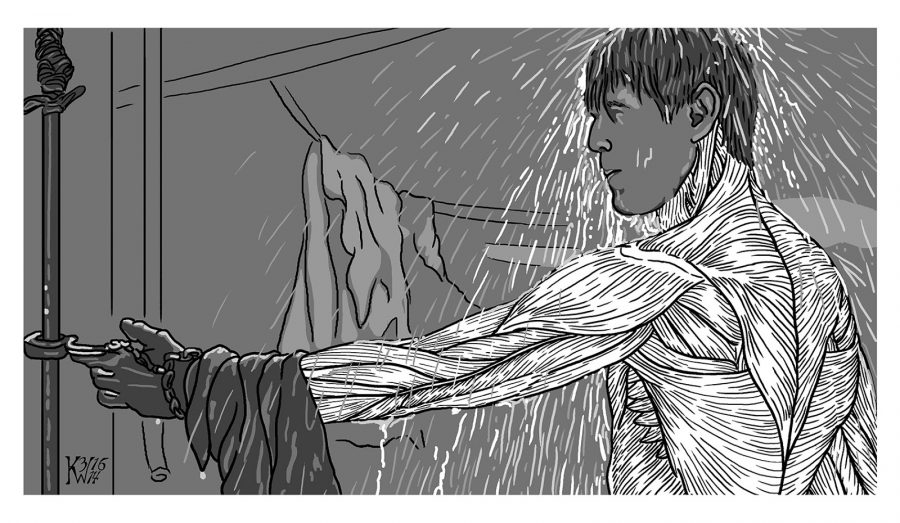

Remember the scene in Tomorrow Never Dies when sexy double agent Wai Lin handcuffs James Bond to the shower and leaves him there?

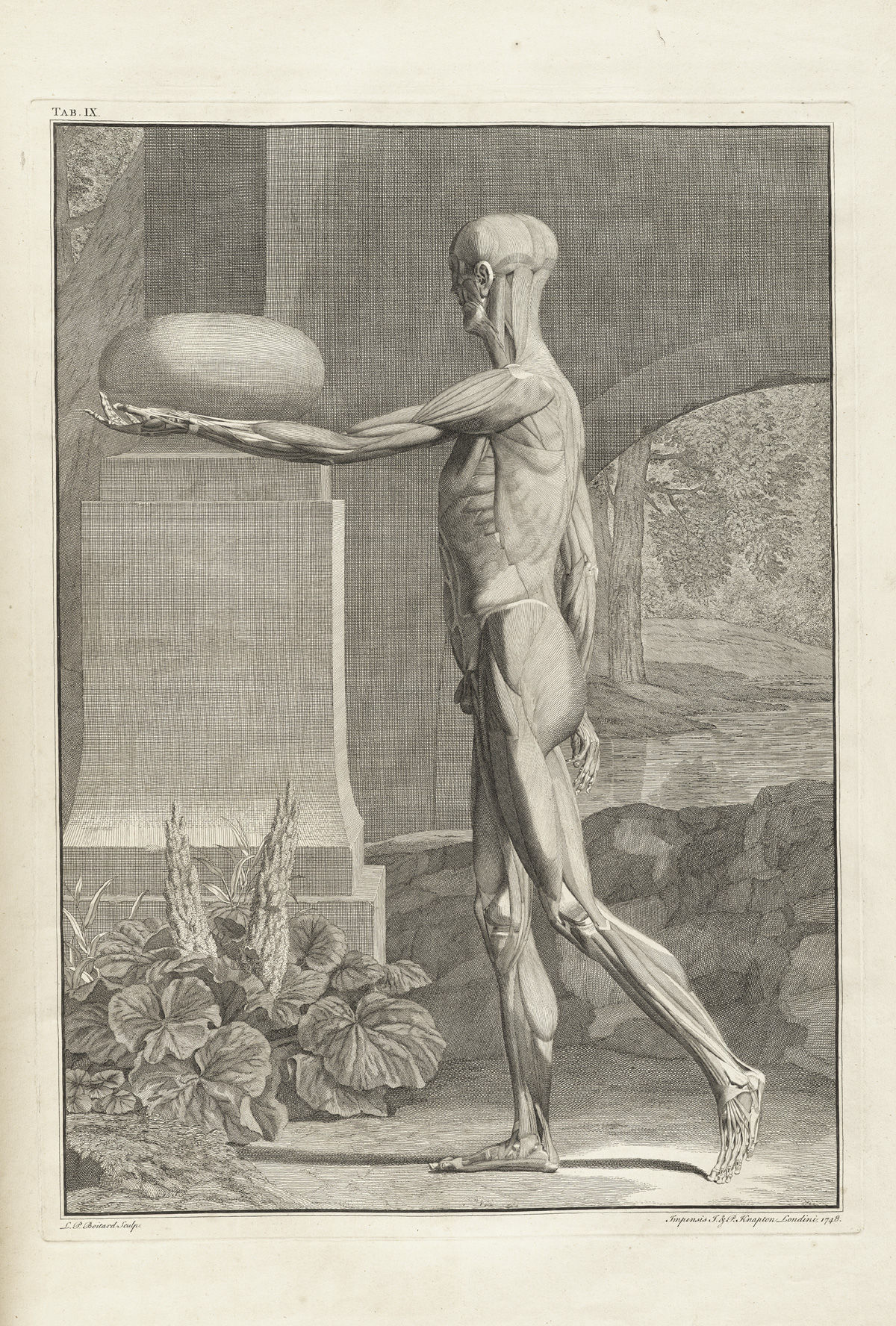

Alternately, remember “Table 9” from anatomist Bernard Siegfried Albinus’ 1749 Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani?

Kriota Willberg, an educator, massage therapist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and author of Draw Stronger: Self-Care For Cartoonists and Other Visual Artists, is sufficiently steeped in both Bond and Albinus to identify striking visual similarities.

That shower scene is just one iconic moment that Willberg included in her mini-comic, Pictorial Anatomy of 007.

Agent Bond’s sartorial sense is a crucial aspect of his appeal, but Willberg, a Bond fan who’s seen every film in the canon at least five times, digs below that celebrated surface, peeling back skin to expose the structures that lie beneath.

Sean Connery’s Bond exhibits a veteran artist’s model’s stillness waiting for the right time to make his move against Dr. No’s “eight-legged assassin.” Even before Willberg got involved, it was an excellent showcase for his pecs, delta, and sternocleitomastoid muscles.

Leaving her flayed Bonds in their cinematic settings are a way of paying tribute to the antique anatomical illustrations Willberg admires for their dynamism:

…sitting in a chair, taking a stroll, holding its skin or organs out of the way so that the reader can get a better look at deeper structures. Some of the cadavers are very flirty. The pictures remind us that we are the organs we see on the page. They do stuff!

The New York Academy of Medicine selected Willberg as its first Artist in Residence, because of the way she explores the intersections between body sciences and artistic practices. (Other projects include an intricate needlepoint X‑Ray of her own root canal and Stitchin’ Time!, a fictional encounter in which Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE), author of De Medicina, and surgeon Aelius Galenus (129 – c. 200 CE) team up to repair a disemboweled gladiator.

Is there a squeamish bone in this artist’s body?

All signs point to no.

Asked to pick a favorite Bond movie, she names Goldfinger for the mythology concerning the infamous scene wherein a beautiful woman is painted gold, but also 2006’s Casino Royale for keeping the torture scene from the book:

I didn’t think they’d have the balls! Sorry! Poor taste but I couldn’t resist. Although Timothy Dalton physically resembled Bond as described in the books, most of the movies make Bond out to be smarter than Fleming wrote him. I think Judy Dench called Daniel Craig, Casino Royale’s Bond, a “blunt instrument” which is pretty much how he’s written. He’s tough and lucky and that’s why he’s survived. Plus the machete fight is great.

Sometimes people get too prissy about the body. I am meat and liver and sausage and so are you. Your body is inescapable while you live. You should get to know it. Think about it in different contexts. It’s fun!

When From Russia With Love’s Rosa Klebb punches master assassin, Red Grant, in the stomach, she is squishing a living liver through living abdominal muscles.

Hard copies of Kriota Willberg’s anatomy-based comics, including Pictorial Anatomy of 007, are available from Birdcage Bottom Books.

Listen to an hour-long interview with Comics Alternative in which Willberg discusses her New York Academy of Medicine residency, anatomical research, and the ways in which humor informs her approach here.

Related Content:

The Spellbinding Art of Human Anatomy: From the Renaissance to Our Modern Times

Free Online Biology Courses

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her latest script, Fawnbook, is available in a digital edition from Indie Theater Now. Follow her @AyunHalliday.