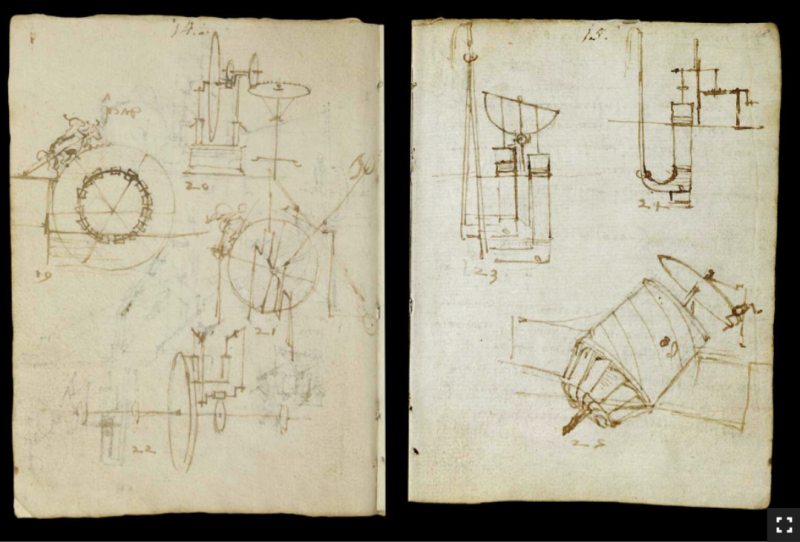

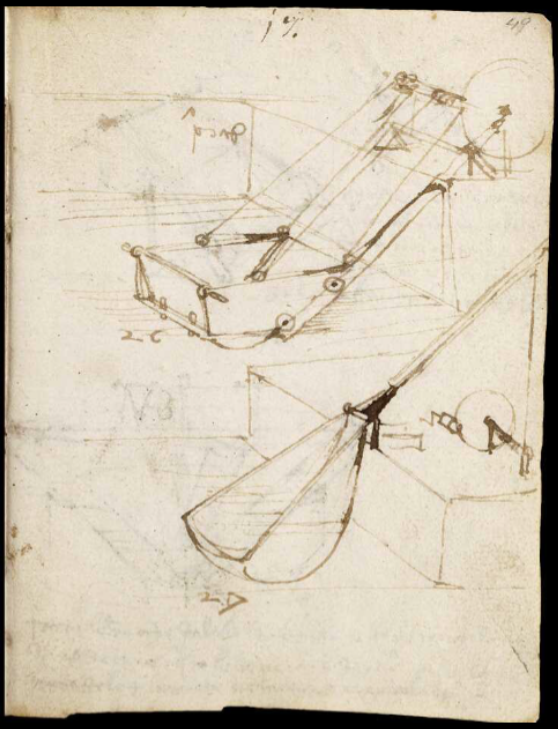

Alejandro Jodorowsky may never have made his film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune, but plenty came out of the attempt — including, one might well argue, Blade Runner. Making that still hugely influential adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Ridley Scott and his collaborators looked to a few key visual sources, one of them a two-part short story in comic form called “The Long Tomorrow.”

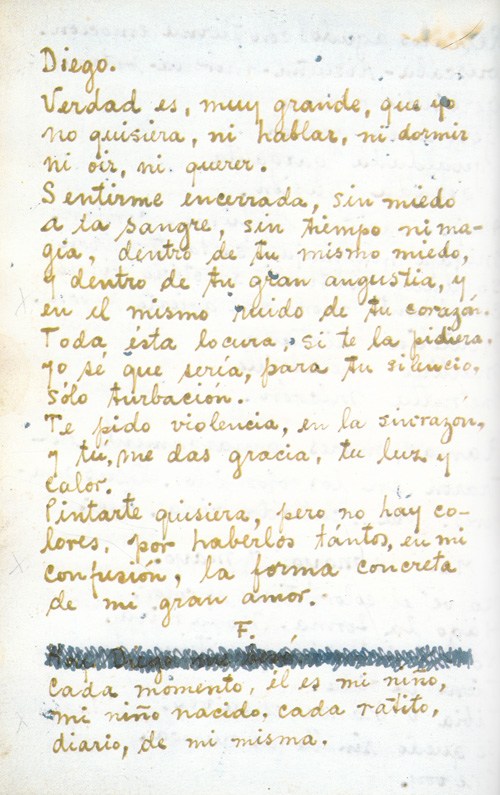

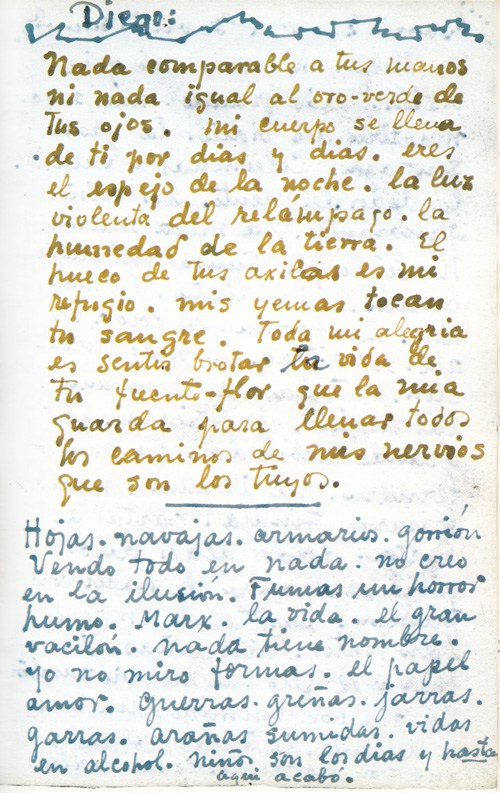

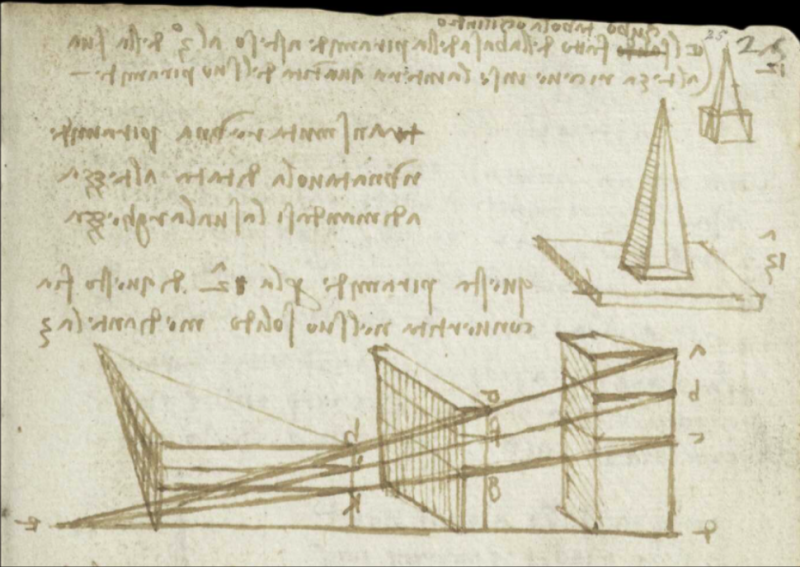

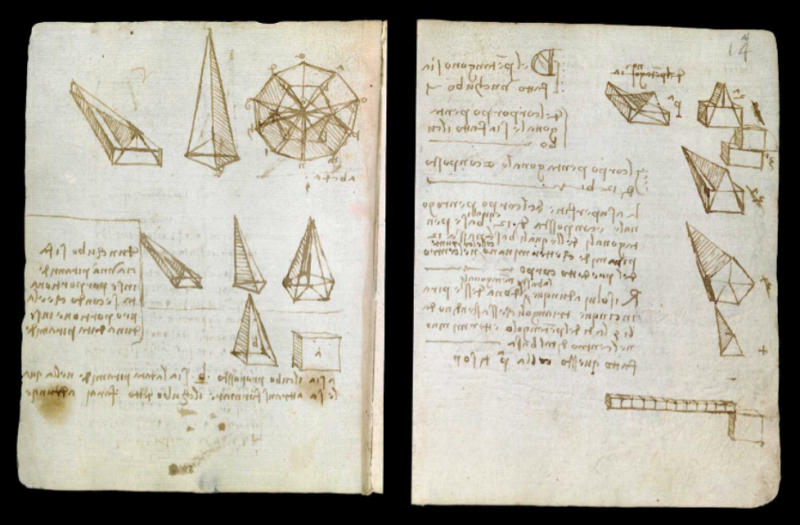

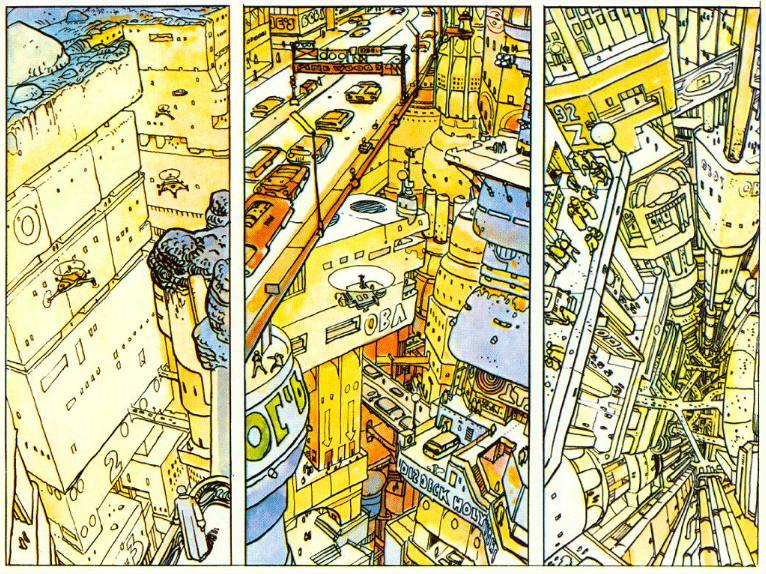

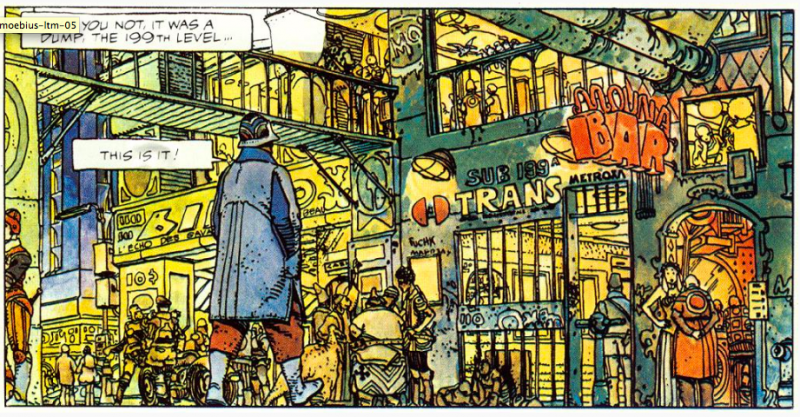

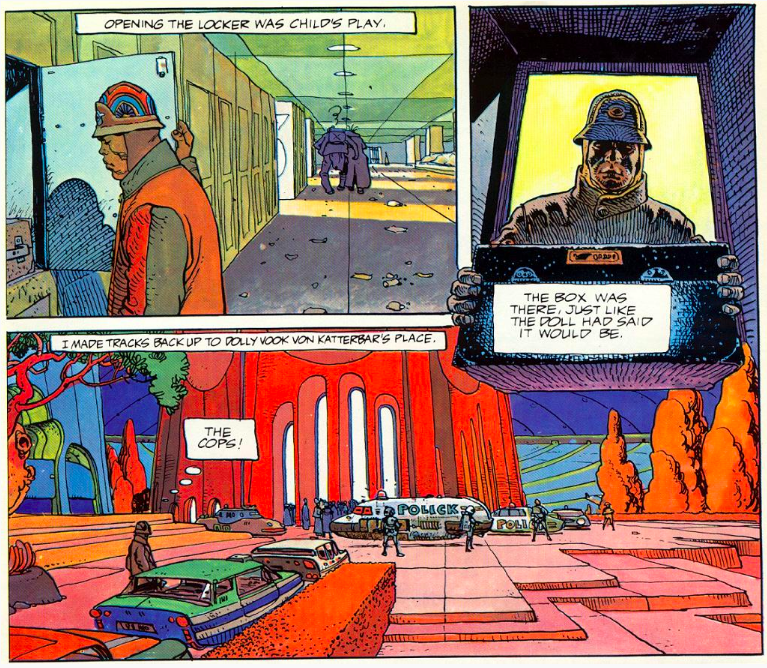

Illustrated by none other than French artist Mœbius, one of the richest visual imaginations of our time, it tells the futuristic hard-boiled story of a private detective in a dense, vertical underground city filled with androids, rowdy bars, assassins, and flying cars. “I’m a confidential nose,” says the protagonist by way of introduction. “My office is on the 97th level. Club’s the name, Pete Club.”

Then comes the fateful piece of narration that begins any detective story worth its salt: “It started out a day like any other day.” But by the end of that day, Club has taken a job from a classic dame in need, fended off both a four-armed thug and a hired assassin, slain an alien monster with whom he finds himself in bed, and recovered the president’s missing brain.

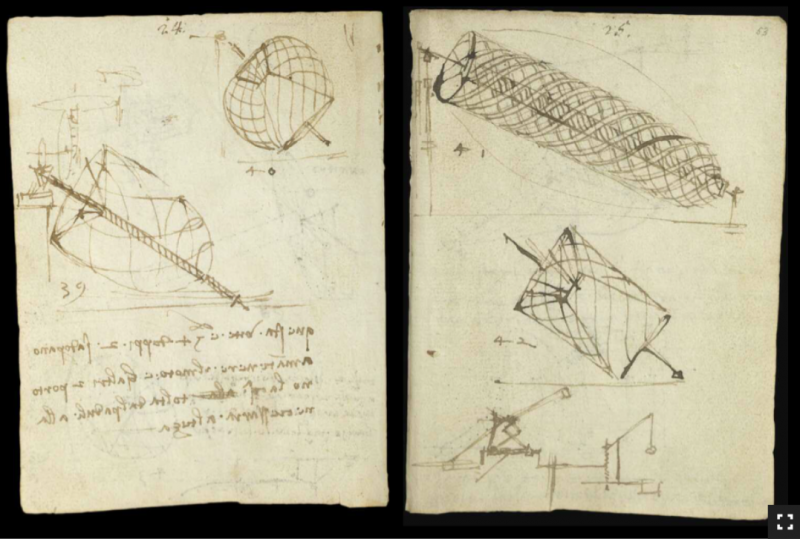

The story was written written by Dan O’Bannon, then known mainly for the film Dark Star, a science-fiction comedy he’d made with his University of Southern California classmate John Carpenter. On the strength of that, Jodorowsky had brought him onto Dune to work on its special effects, just as he’d brought Mœbius on to create its storyboards and concept art. With nothing to do before shooting began — which it never did — O’Bannon first drew “The Long Tomorrow” himself as a way of keeping busy. Mœbius took one look at it and immediately saw its promise.

The French may have coined the term film noir, but this early work of future noir benefited from having an American writer. “When Europeans try this kind of parody, it is never entirely satisfactory,” Mœbius writes in the introduction to the book version of “The Long Tomorrow.” “The French are too French, the Italians are too Italian … so, under my nose was a pastiche that was more original than the originals.” It also, with Mœbius’ art, laid the visual groundwork for generations of sci-fi stories to come.

“The way Neuromancer-the-novel ‘looks’ was influenced in large part by some of the artwork I saw in Heavy Metal,” said William Gibson, referring to the English version of Métal hurlant, the magazine that popularized Mœbius’ work. (O’Bannon also worked on the animated Heavy Metal anthology film, released in 1981.) But perhaps Ridley Scott, who started working with the artist on 1979’s O’Bannon-scripted Alien, described the influence of Mœbius’ art on our visions of the future best: “You see it everywhere, it runs through so much you can’t get away from it.” In a cultural sense, all of us live in Pete Club’s city now.

Related Content:

Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

The Blade Runner Sketchbook Features The Original Art of Syd Mead & Ridley Scott (1982)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.