I am not equipped to judge whether the notorious Aleister Crowley—whom the British press once called “the wickedest man in the world”—was an overrated magician (or “Magick-ian”). His banishment from the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, by none other than William Butler Yeats, may not speak well of him. But this is an area of debate best left to experts in the mystic arts.

Nor do I feel qualified to venture an opinion on Crowley’s mountaineering. It’s true, he did not reach the summit of K2, but he gets more than partial credit as part of the first expedition to make the attempt in 1902.

As for Crowley the poet… well, he was a lesser literary talent than his rival Yeats, whom he supposedly envied. One writer remarks of the conflict between them that Crowley “was never able to speak the language of poetic symbol with the confidence of a native speaker in the way Yeats definitely could.”

Still, many of his poems have an undeniably enchanting quality. Their obscure mythic depths show the prominent influence of William Blake. Others, like the obscenely puerile “Leah Sublime” derive from the libertine tradition of John Wilmot.

What of Crowley the painter? I must say, until recently, I knew little of this side of him, though I’ve had many encounters with this weird character’s life and work. While longtime fans and followers surely know his visual art well, the casually curious rarely get a glimpse.

Crowley, writes Robert Buratti at Raw Vision, “has never been as well known for his artistic pursuits as for his more esoteric interests,” and that especially goes for his painting. His art apparently did not pique the prurient interest of the tabloids, the primary source of his popular fame, but maybe it deserves at least as much attention as his spellwork and sex magic.

Buratti, a Crowley disciple of Thelema and member of the Art Guild of Ordo Templi Orientis Australia, curated a 2013 exhibition called Windows to the Sacred that featured several of Crowley’s paintings. He argues that Crowley’s “significance as an artist lies in his reconsideration of art as a central component in his magical theory of the universe and, in particular, its ability to awaken, as he put it, ‘our Secret Self—our Subconscious Ego, whose magical Image is our individuality expressed in mental and bodily form.”

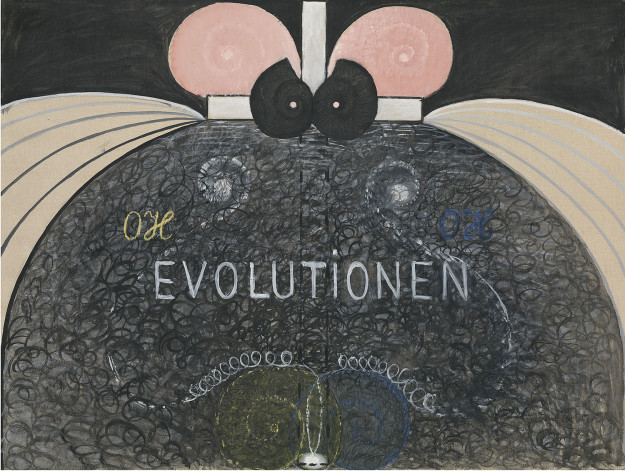

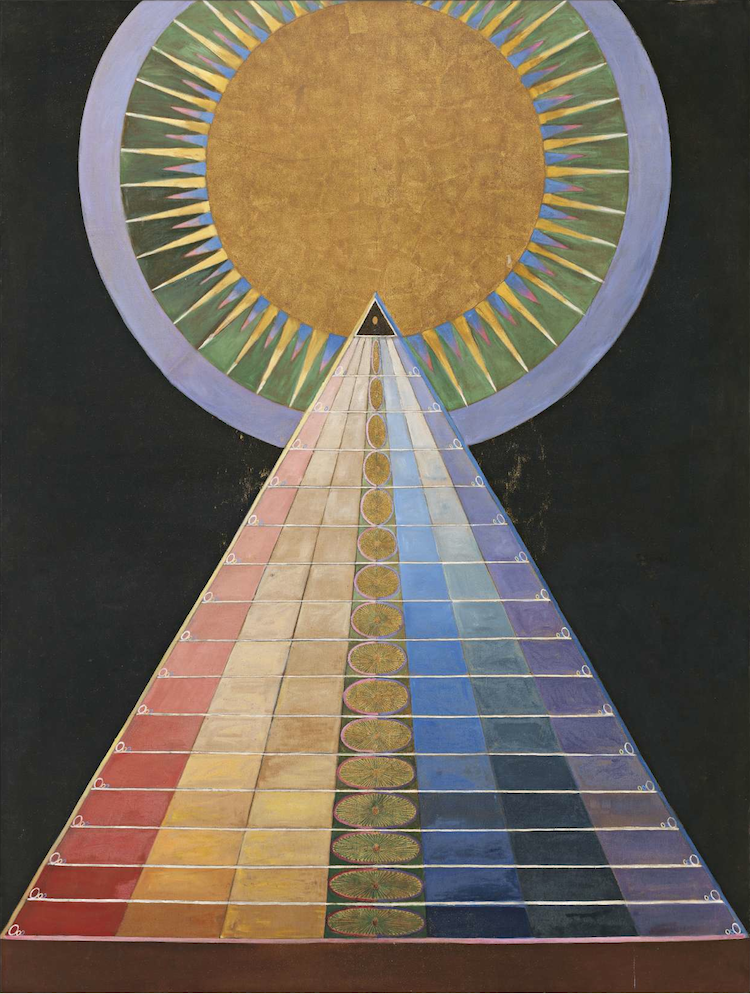

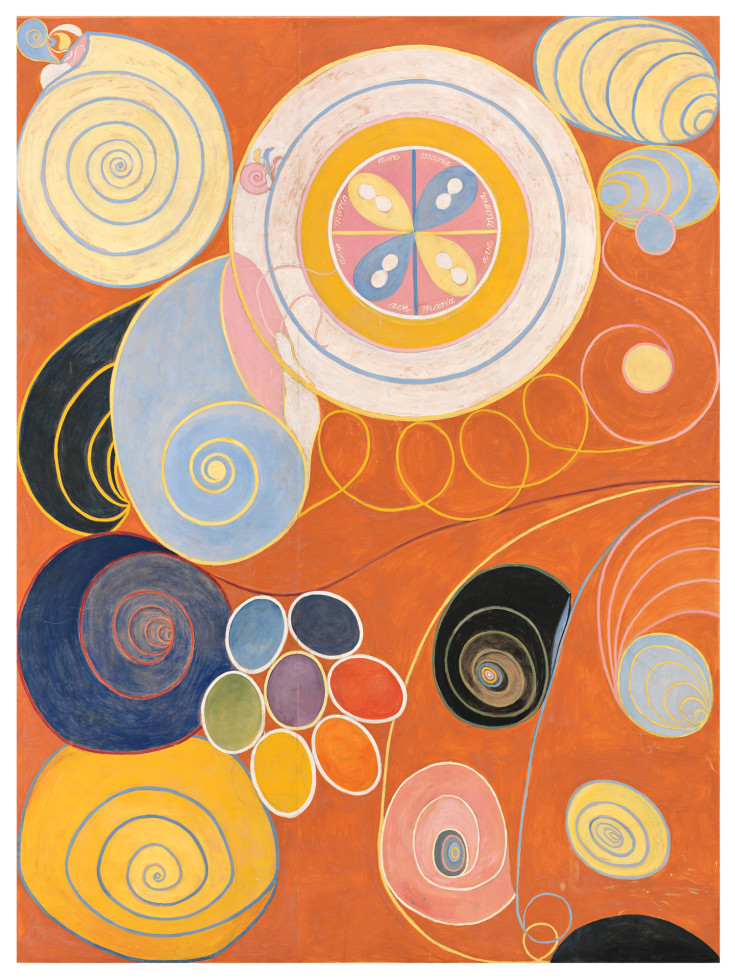

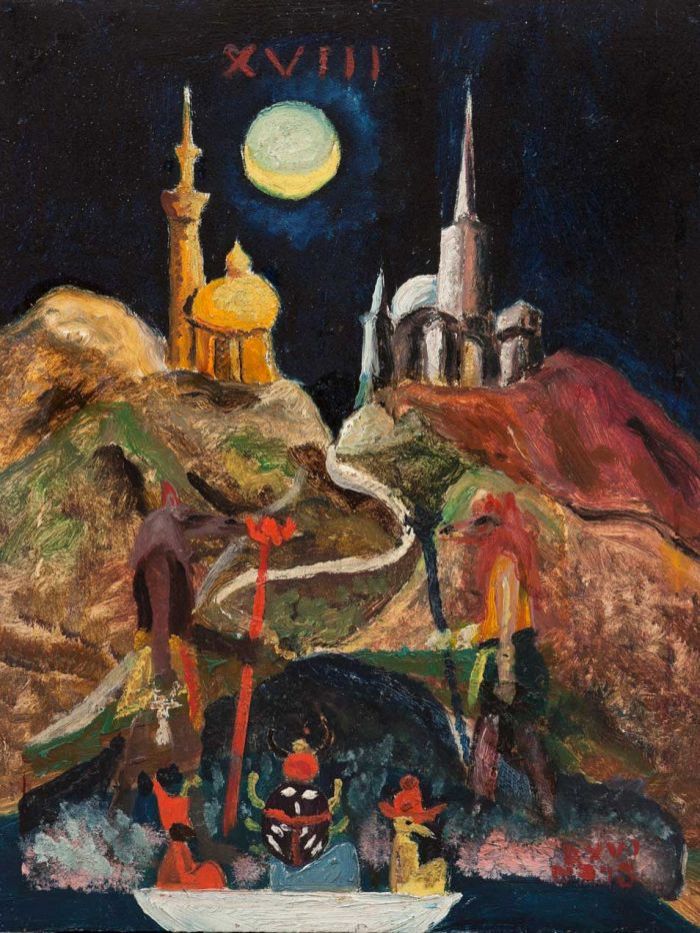

As for the formal properties of the paintings themselves, Buratti references the Surrealists, and notes in an interview that Crowley “was quite inspired by Paul Gauguin.” The paintings’ rough, childlike primitivism also resembles the technique of artists like Georges Rouault and the early, pre-abstraction Wassily Kandinsky.

Who knows whether “The Great Beast 666,” as Crowley liked to call himself, would take these comparisons as a compliment. But I expect it takes a true adept to unravel the mysteries of enigmatic works from 1920–21 like The Sun (Auto Portrait), at the top, The Moon (Study for Tarot), further down, or The Hierophant, below. Avant-garde filmmaker Kenneth Anger is such an adept, a convert to Crowley’s religion, which exerted much influence on his work.

Above, see Anger’s “Brush of Baphoment,” a short film in which his camera zooms and pans over Crowley’s paintings, picking up mystical symbols and intriguingly indecipherable symbolism. And learn more about Crowley’s visual art in this radio interview with Buratti and his edited collection of Crowley’s work, The Nightmare Paintings.

Related Content:

Aleister Crowley Reads Occult Poetry in the Only Known Recordings of His Voice (1920)

The Thoth Tarot Deck Designed by Famed Occultist Aleister Crowley

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness