Got a knack for drawing, painting, sculpting, creating handmade objects of any kind? You’re maybe more likely to monetize your skill—with an Etsy or Pinterest account, for example—than move to New York and try to make a go of it. Were such convenient means of setting up shop available in the late 40’s, when Andy Warhol studied art education and commercial art at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, respectively, one wonders whether the often bedridden, introverted artist might have found it more appealing to work from home in Pittsburgh, and stay there.

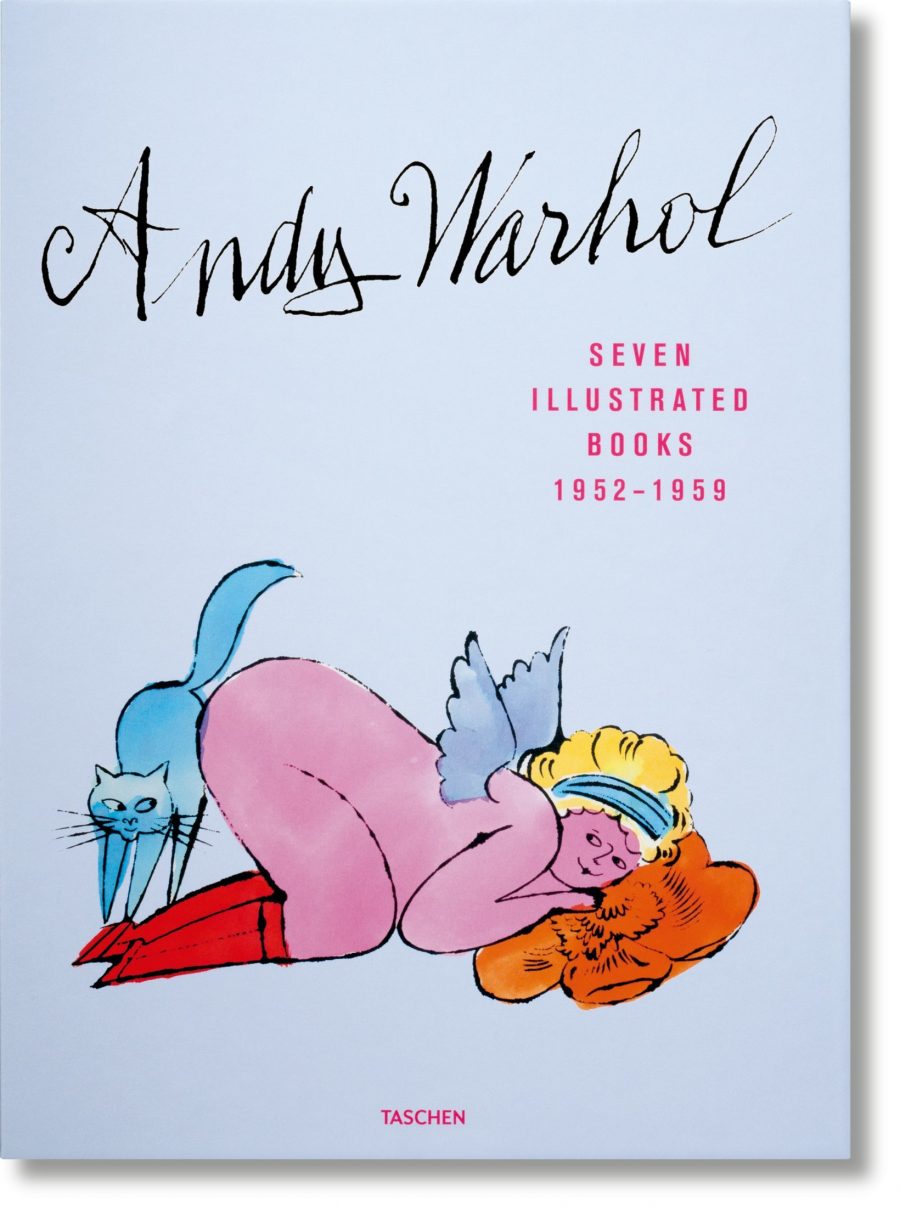

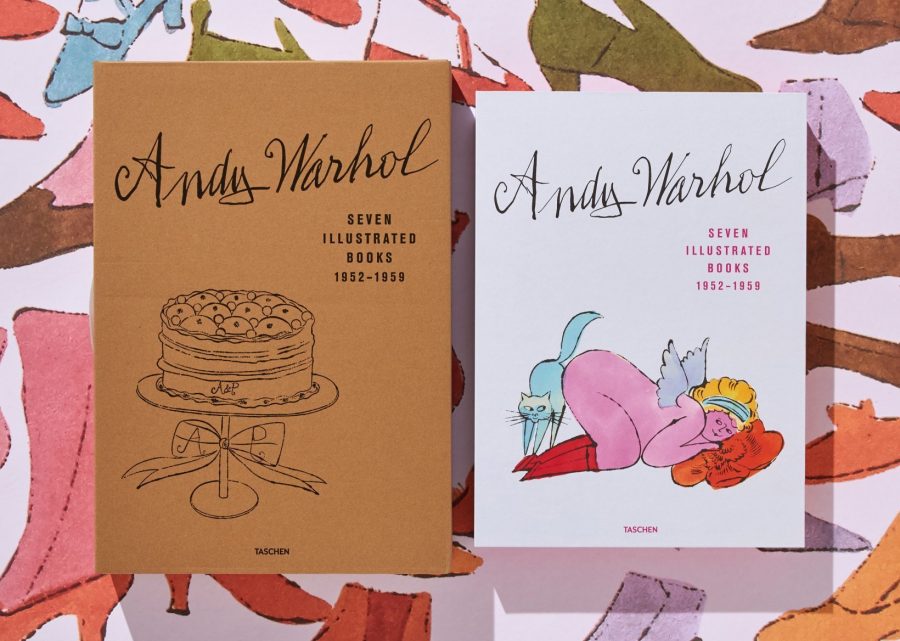

Instead, he moved to New York and became a successful commercial artist by using his illustration skills to market himself. Before he was a “bellwether of post-war and contemporary art” with those famous silkscreen paintings in the 60s; before he made those famous films, discovered (and invented the concept of) art stars, and managed the Velvet Underground, Warhol created seven handmade books “as part of his strategy to woo clients and forge friendships.” So writes Taschen books, who have collected and reprinted Warhol’s art books in a single edition. (Five of the seven have never before been republished.)

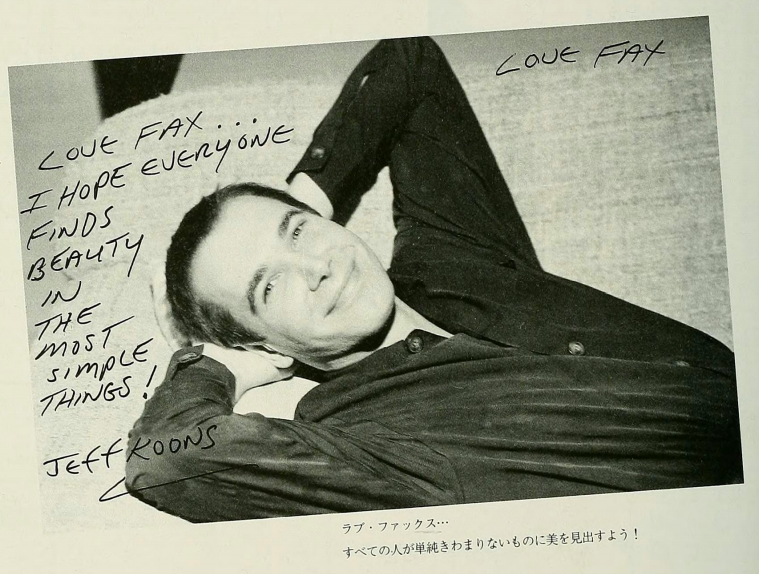

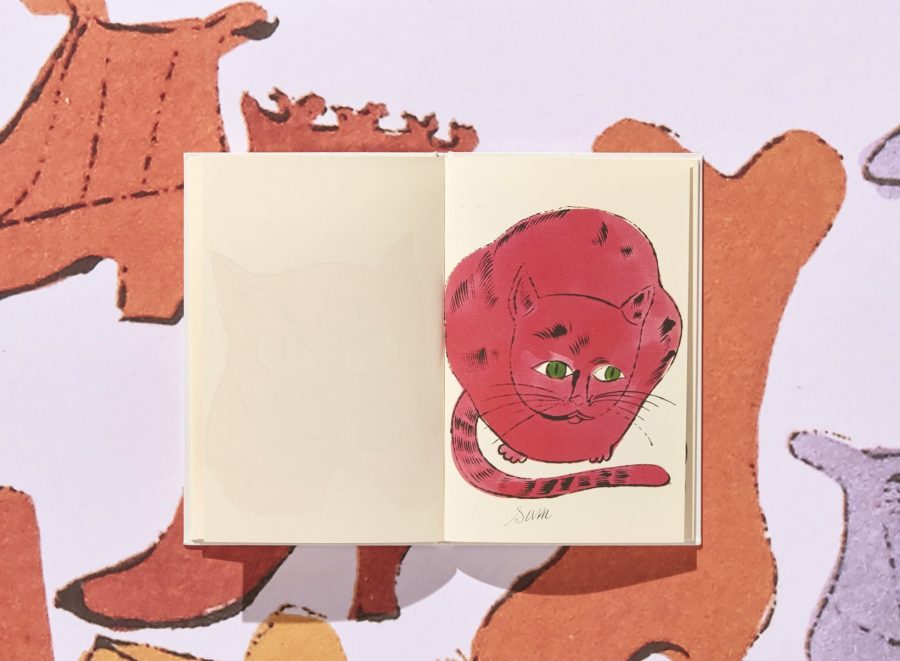

Warhol reserved the signature books for “his most valued contacts. These featured personal, unique drawings and quirky texts revealing his fondness for—among other subjects—cats, food, myths, shoes, beautiful boys, and gorgeous girls.”

They are intimate and charming, showing a side of the artist we don’t often see—but one we do see of so many contemporary illustrators. His hand-drawn illustrations have a very 21st century feel to them in their obsession with cats, cakes, fashion, and happy, nude zaftig beauties. Created between 1952 and 59, they could have come from any number of illustration or design sites. It’s easy to imagine a current-day Warhol making a living selling work like this online.

Had he been able to do so, might he have become a different kind of artist entirely? It’s impossible to say. I can imagine a number of people for whom I might buy copies of Love Is a Pink Cake, 25 Cats Named Sam, or À la Recherche du Shoe Perdu, as a holiday gift. But Warhol didn’t make copies of these books. He saved the mass production for his later gallery work. Instead the handmade calling cards remain “little-known, much-coveted jewels in the Warhol crown,” early examples of “the artists’ off-the-wall character as well as his accomplished draftsmanship, boundless creativity, and innuendo-laced humor.”

You might not know it from canvases like Eight Elvises, the Marilyn Monroe series, or Campbell’s Soup Cans, but Warhol had a particular talent for light, whimsical hand-drawn illustration. It’s a side of himself he showed few people once he became the Andy Warhol most of us know. Thanks to Taschen’s new book, a recent gallery showing of Warhol’s drawings, a 2012 Chronicle collection of his quirky illustrations from the 50s, and, well, Pinterest, it’s a side of him that can now belong to everyone.

You can now get your own copy of Andy Warhol: Seven Illustrated Books 1952–1959.

Related Content:

The Big Ideas Behind Andy Warhol’s Art, and How They Can Help Us Build a Better World

Short Film Takes You Inside the Recovery of Andy Warhol’s Lost Computer Art

Miyazaki Meets Warhol in Campbell’s Soup Cans Reimagined by Designer Hyo Taek Kim

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness