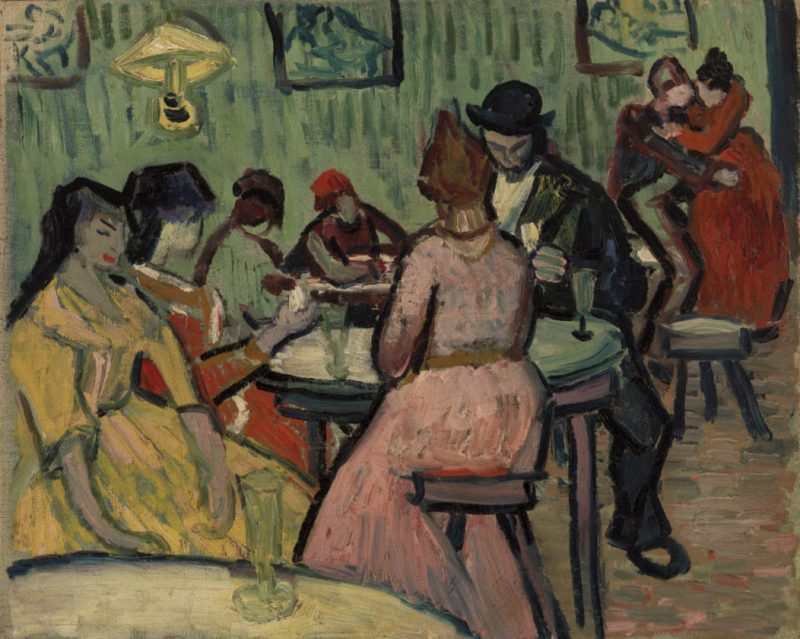

Long ago, we showed you some startling footage of an elderly, arthritic Pierre-Auguste Renoir, painting with horribly deformed hands. Today we offer a more idyllic image of a French Impressionist painter in his golden years: Claude Monet on a sunny day in his beautiful garden at Giverny.

Once again, the footage was produced by Sacha Guitry for his project Ceux de Chez Nous, or “Those of Our Land.” It was shot in the summer of 1915, when Monet was 74 years old. It was not the best time in Monet’s life. His second wife and eldest son had both died in the previous few years, and his eyesight was getting progressively worse due to cataracts. But despite the emotional and physical setbacks, Monet would soon rebound, making the last decade of his life (he died in 1926 at the age of 86) an extremely productive period in which he painted many of his most famous studies of water lilies.

At the beginning of the film clip we see Guitry and Monet talking with each other. Then Monet paints on a large canvas beside a lily pond. It’s a shame the camera doesn’t show the painting Monet is working on, but it’s fascinating to see the great artist all clad in white, a cigarette dangling from his lips, painting in his lovely garden.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

1922 Photo: Claude Monet Stands on the Japanese Footbridge He Painted Through the Years

Impressionist Painter Edgar Degas Takes a Stroll in Paris, 1915

Rare Film of Sculptor Auguste Rodin Working at His Studio in Paris (1915)

Watch Henri Matisse Sketch and Make His Famous Cut-Outs (1946)