Popular food culture is dominated by status symbols of restaurant-inspired consumer kitchenware and appliances, thanks in large part to reality televisions shows about cooking competitions which can make the preparation of haute cuisine seem more accessible to the average home chef than it may actually be.

Many would argue, however, that we’ve come a long way since the 70s, when the mass-market products that held sway over best-selling cooking guides went by names like Hamburger Helper, Cool Whip, and Jello. Back then, willful anachronism Salvador Dali stepped into this commercial landscape with his 1973 cookbook Les Diners de Gala, offering aristocratic, extravagant recipes—next to even more extravagant art—with exotic ingredients often impossible to find at the local supermarket both then and now.

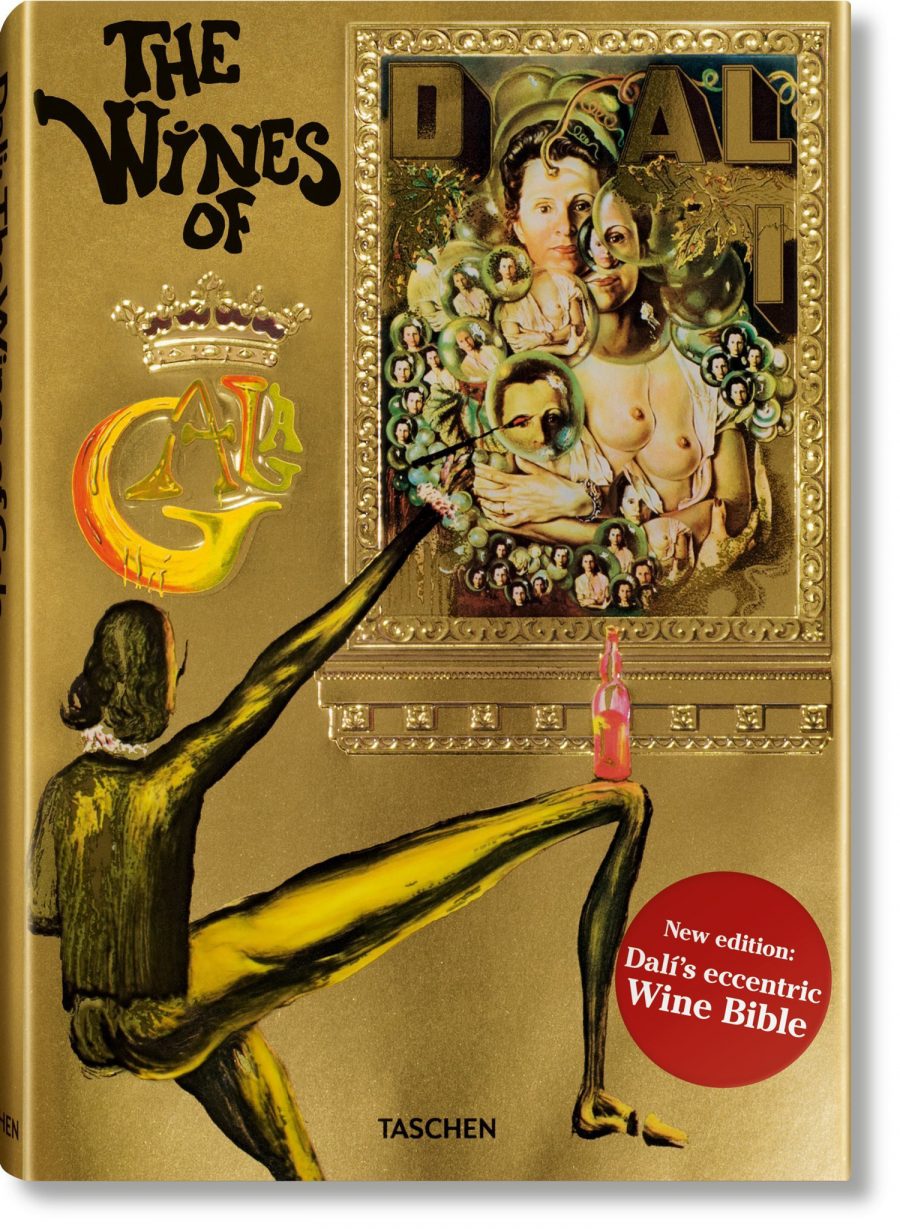

Dali made it plain that his object was to bring back pure pleasure to dining, the adventurous opulence he and his wife, Gala, so appreciated in their own outsized social lives. A few years later, Dali did the same thing with the fine-dining beverage of choice, publishing The Wines of Gala, an “eccentric guide to wine grapes and their origin,” writes This is Colossal. The book’s “groupings are appropriate imaginative classifications.”

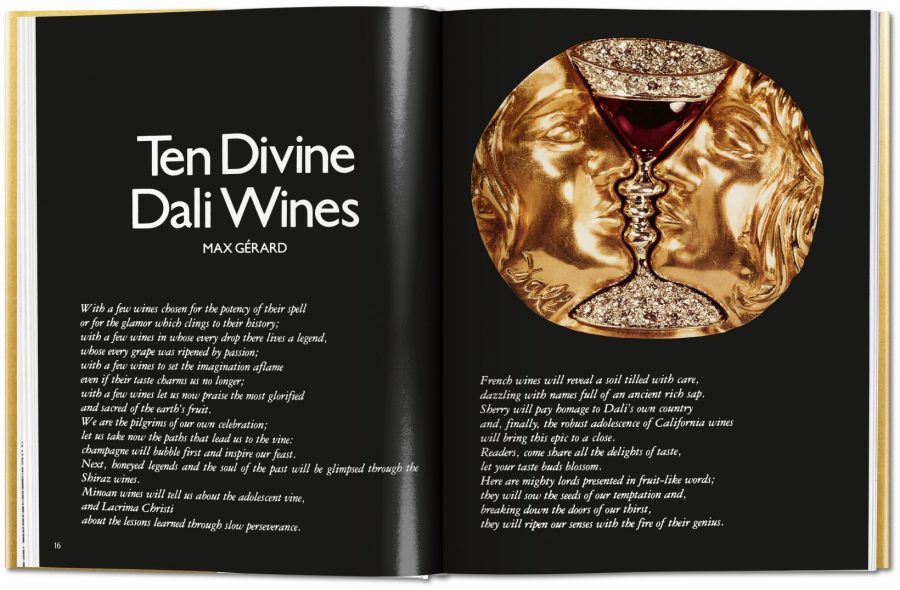

The Wines of Gala splits into two parts: “Ten Divine Dali Wines” and “Ten Gala Wines.” The latter includes categories like “Wines of Frivolity,” “Wines of Joy,” “Wines of Sensuality,” “Wines of Purpose,” and “Wines of Aestheticism.” Among the Divine Dali Wines, we find “The Wine of King Minos,” “Lacrima Christi,” “Chateauneuf-du-Pape,” and “Sherry.” In an appendix, Dali surveys “Vineyards of the World,” generally, and “Vineyards of France,” specifically, and offers “Advice to the Wine-Loving Gourmet.”

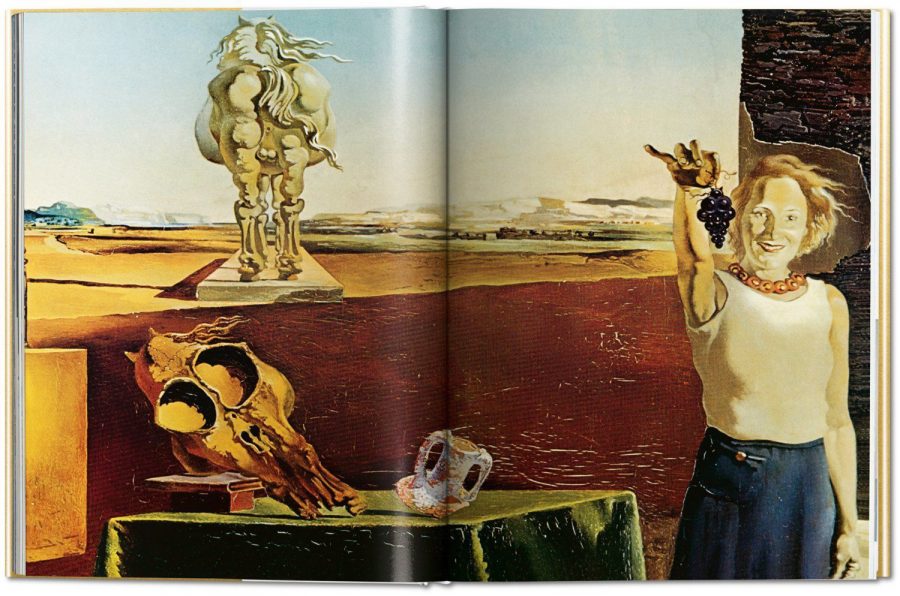

While some of Dali’s wine advice may go over our heads, maybe the real reason we’re drawn to his cookbook and wine guide is the artwork they contain within their pages, likely also the principle reason arts publisher Taschen has reissued both of these publications. The Wines of Gala is due out on November 21, but you can pre-order a hard copy now (or find used copies of the original 1970s edition here). In it you’ll find much bewitching original art to complement the passionate descriptions of wine.

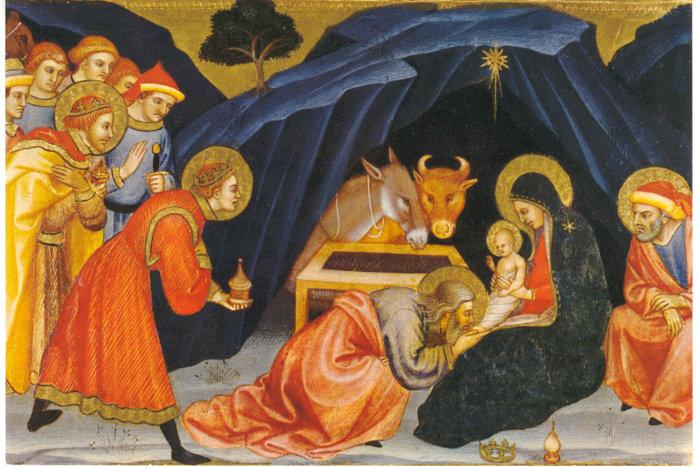

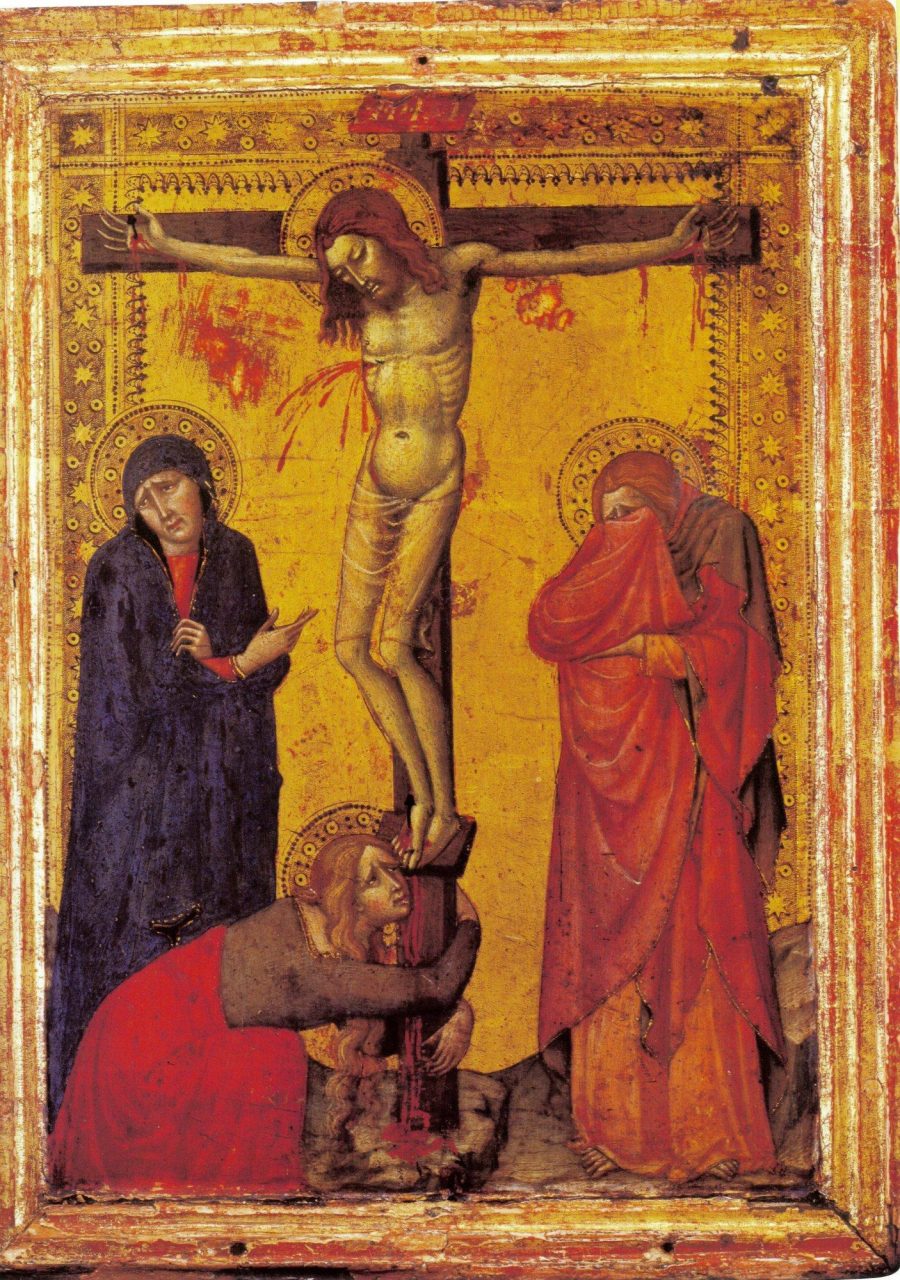

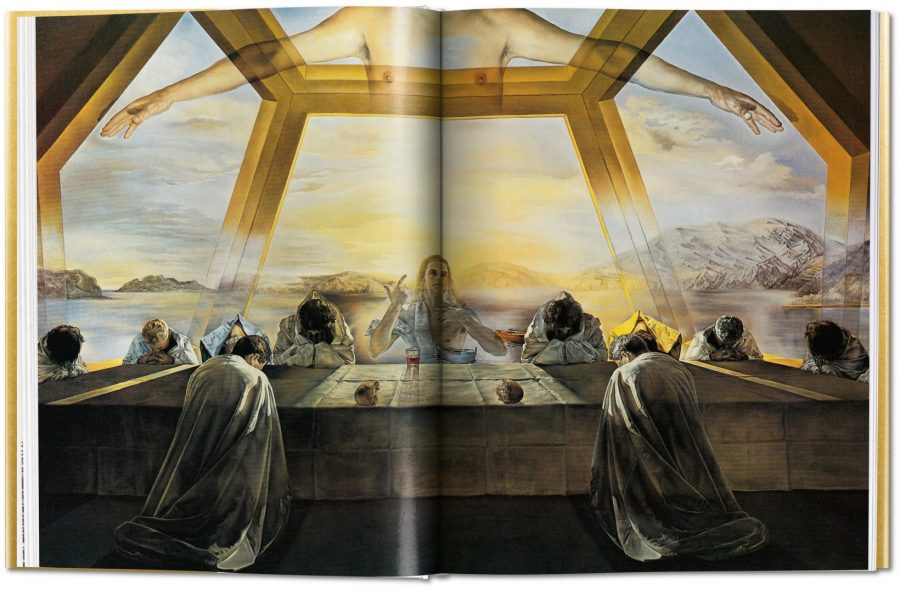

The “rich and extravagant wine bible features 140 illustrations by Dali,” notes Rebecca Fulleylove. “Many of the artworks featured are appropriated pieces, including… a work from Dali’s late Nuclear Mystic phase, The Sacrament of the Last Supper.” Even to this solemn affair, Dali brings “his ability to seek out pleasure and beauty in everything.”

via This is Colossal/It’s Nice That

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

Salvador Dalí Goes Commercial: Three Strange Television Ads

Salvador Dalí’s Melting Clocks Painted on a Latte

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness