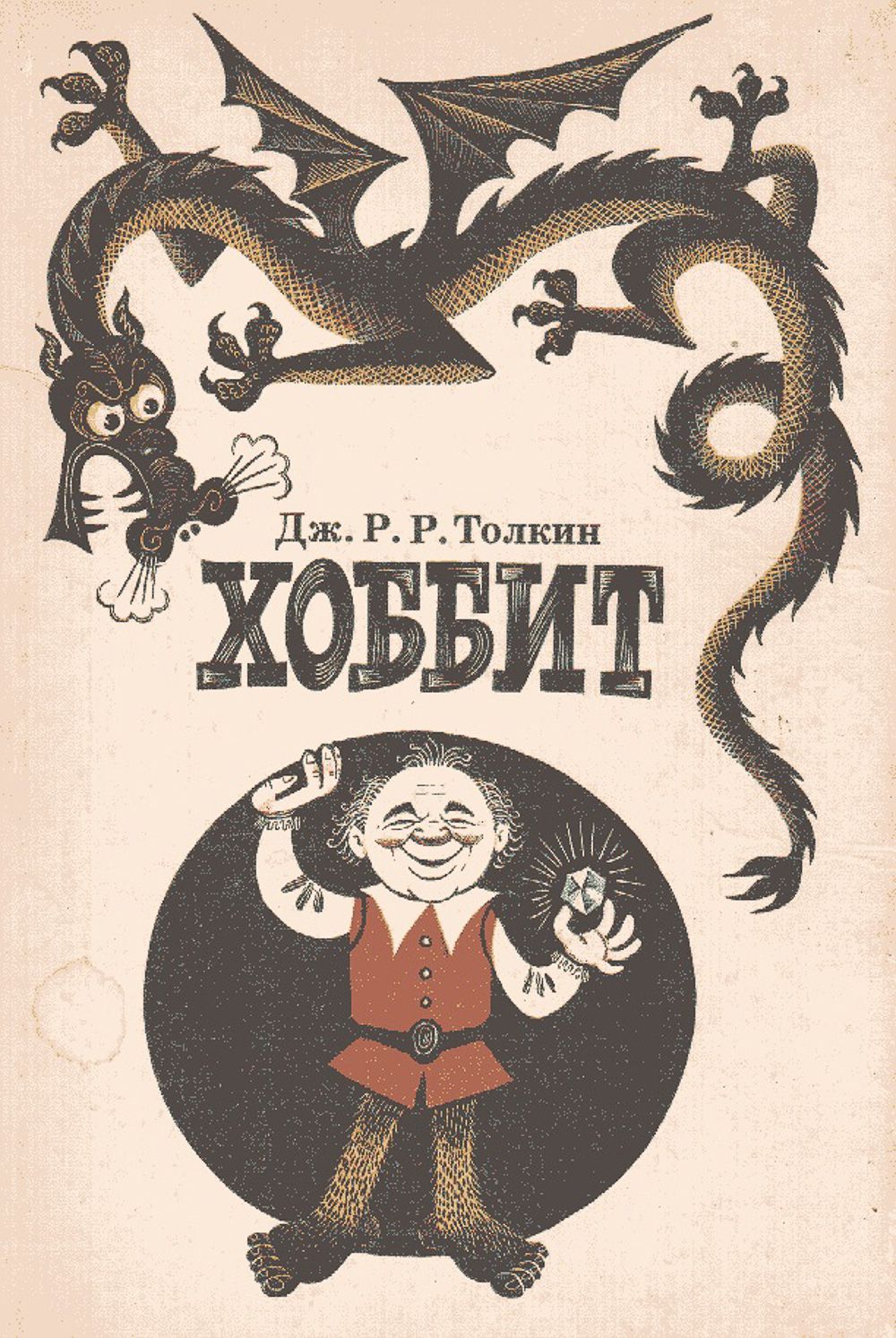

Until I read J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings, my favorite book growing up was, by far, The Hobbit. Growing up in Russia, however, meant that instead of Tolkien’s English version, my parents read me a Russian translation. To me, the translation easily matched the pace and wonder of Tolkien’s original. Looking back, The Hobbit probably made such an indelible impression on me because Tolkien’s tale was altogether different than the Russian fairy tales and children’s stories that I had previously been exposed to. There were no childish hijinks, no young protagonists, no parents to rescue you when you got into trouble. I considered it an epic in the truest literary sense.

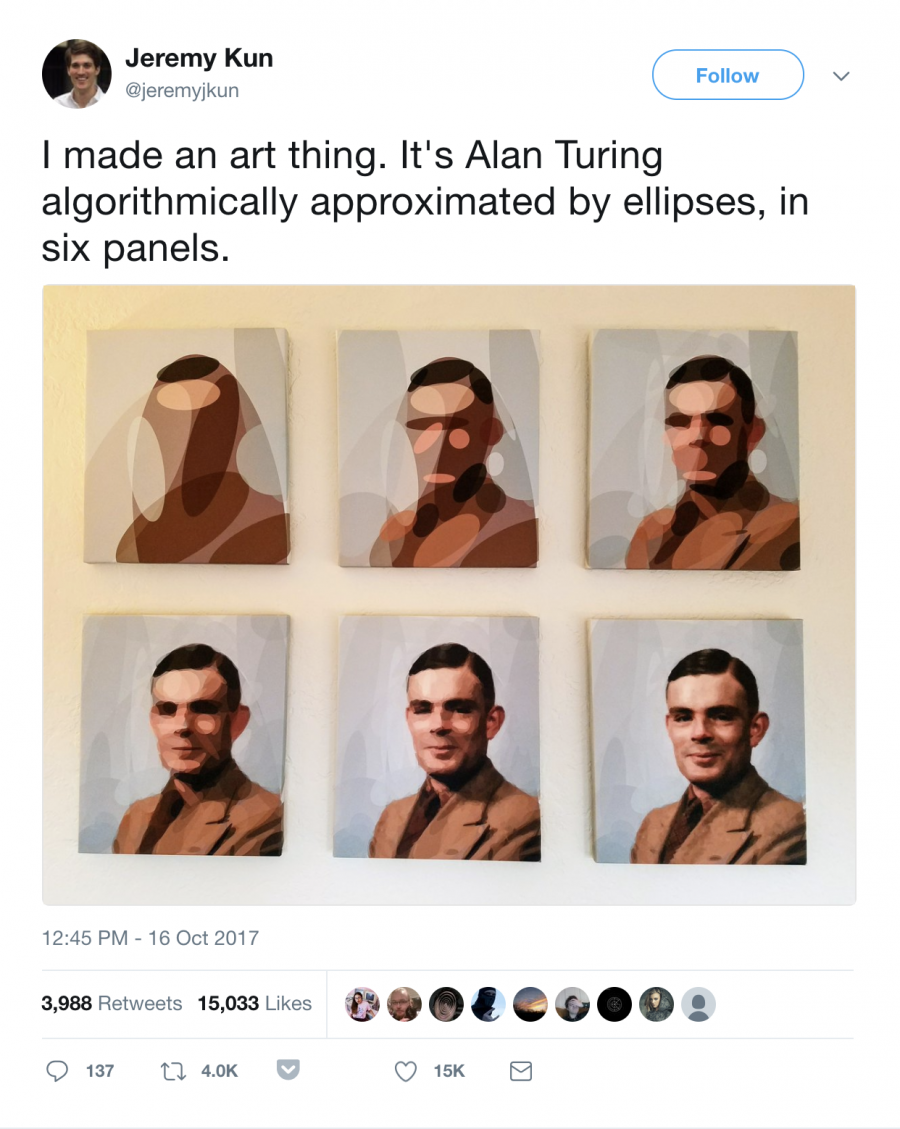

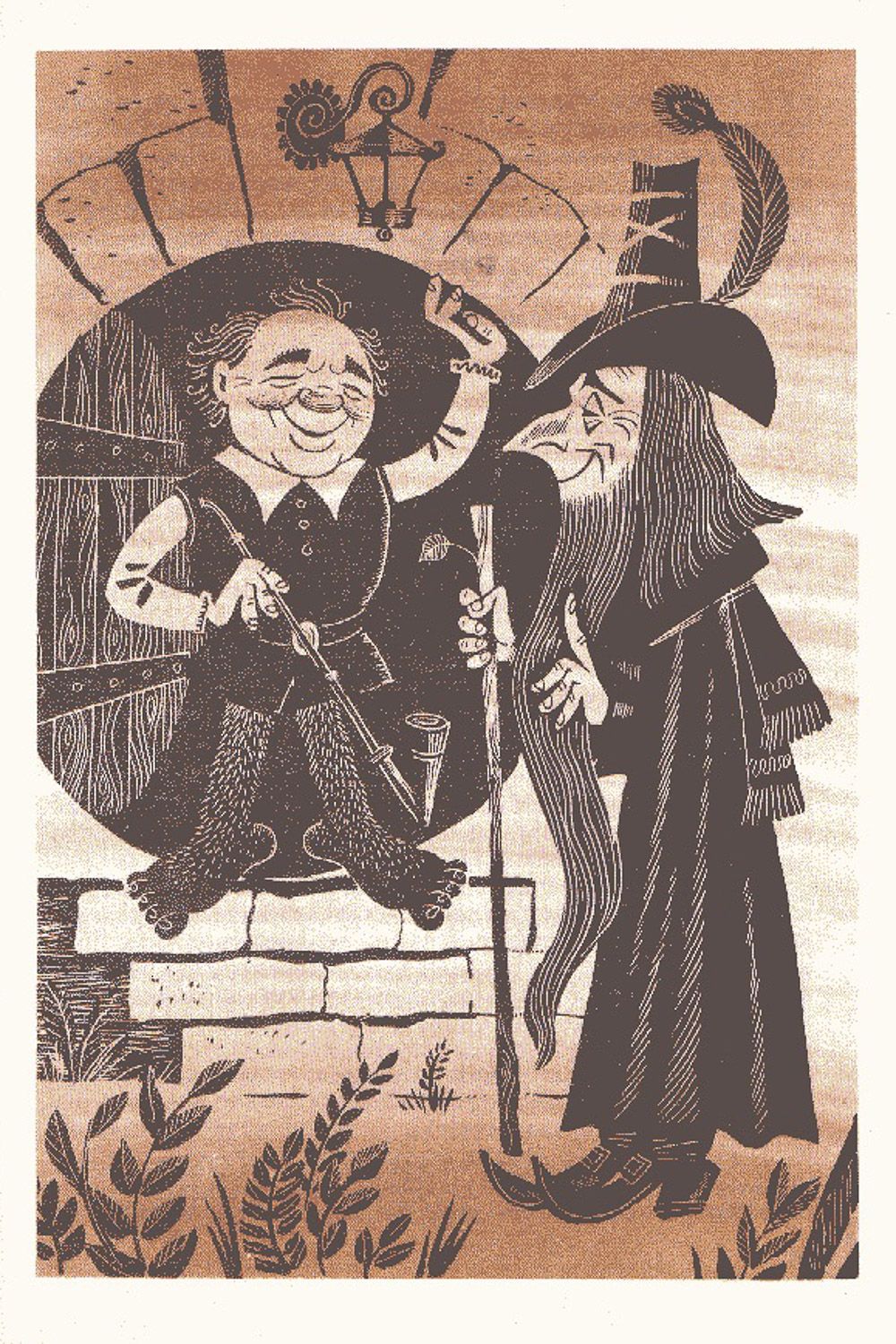

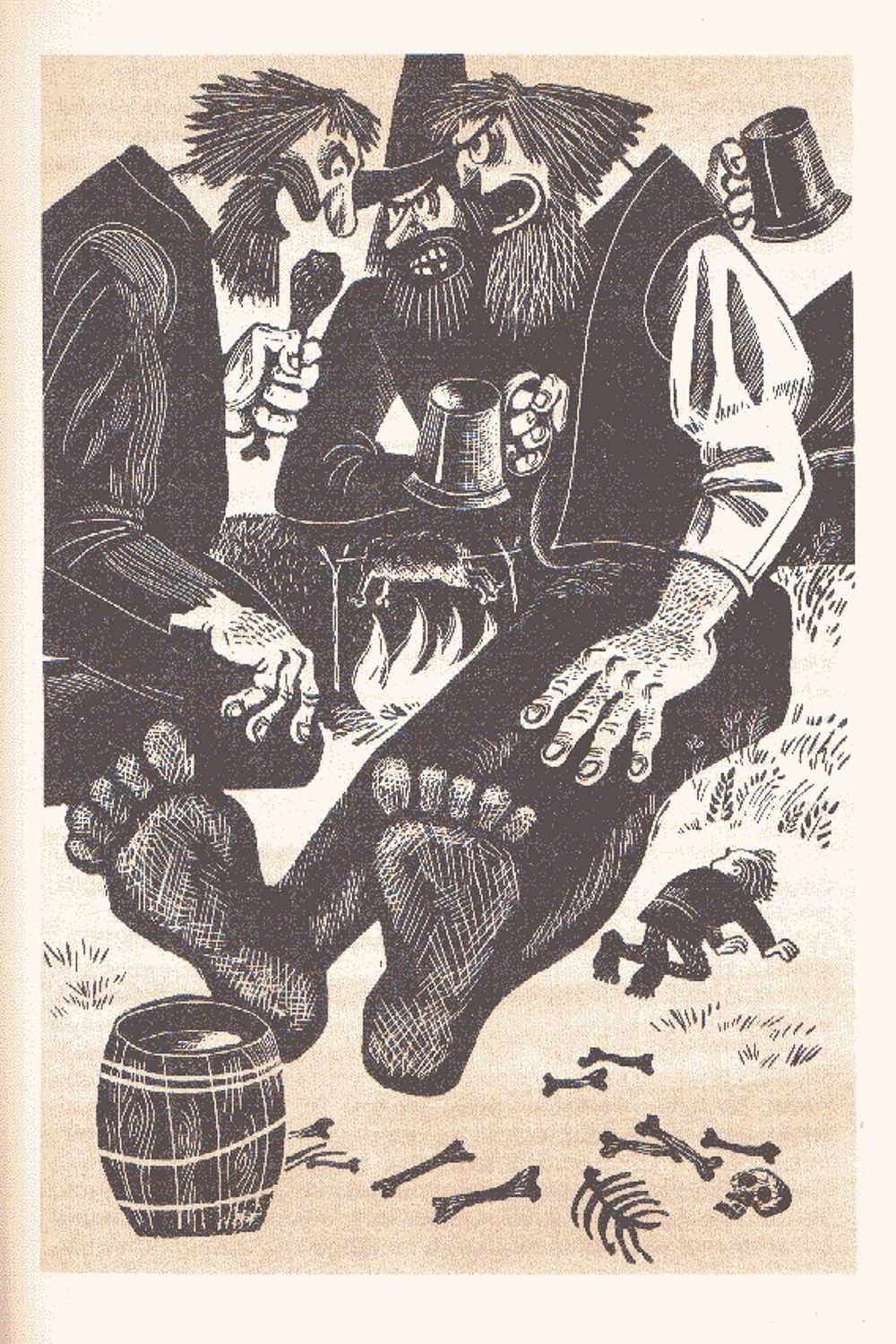

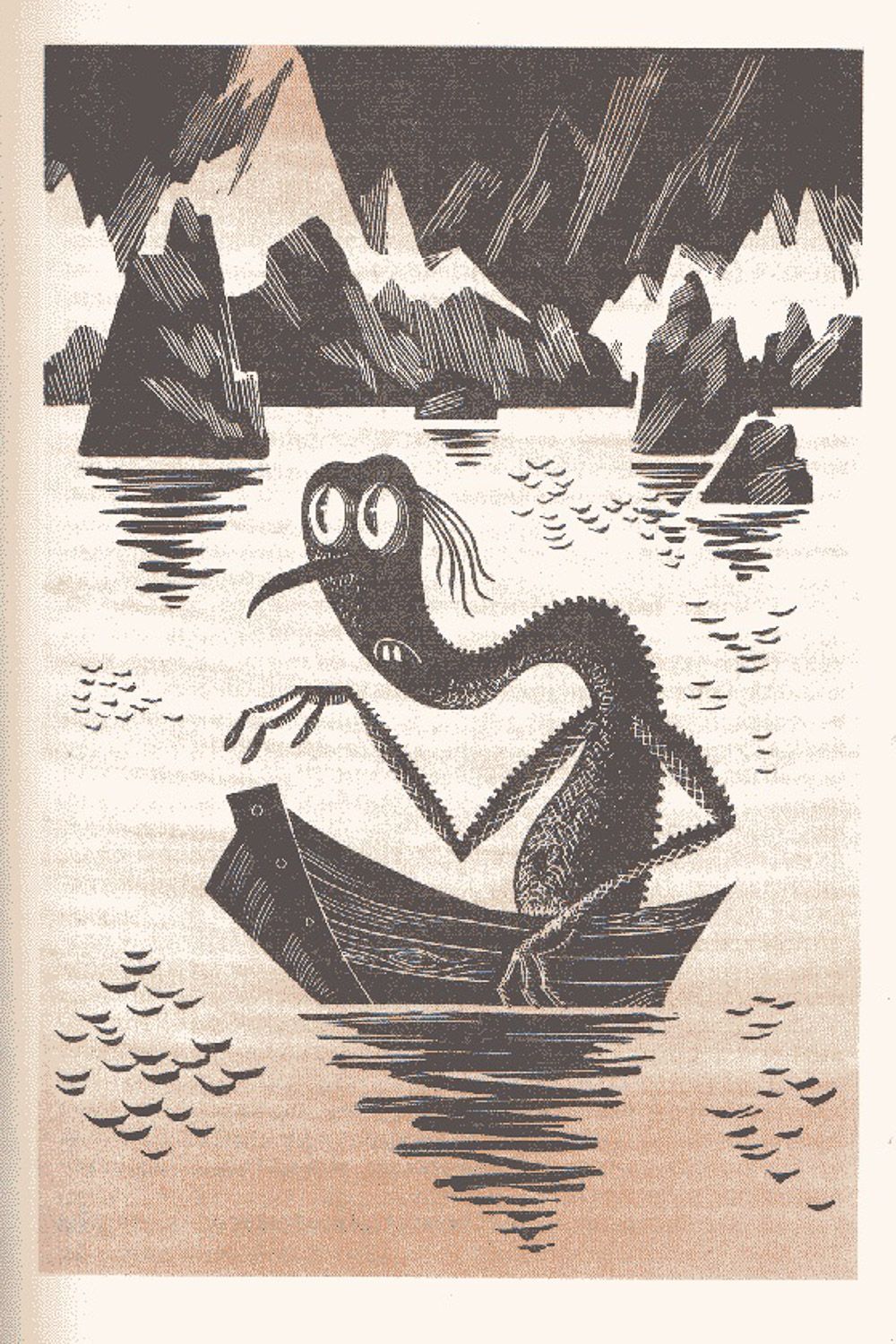

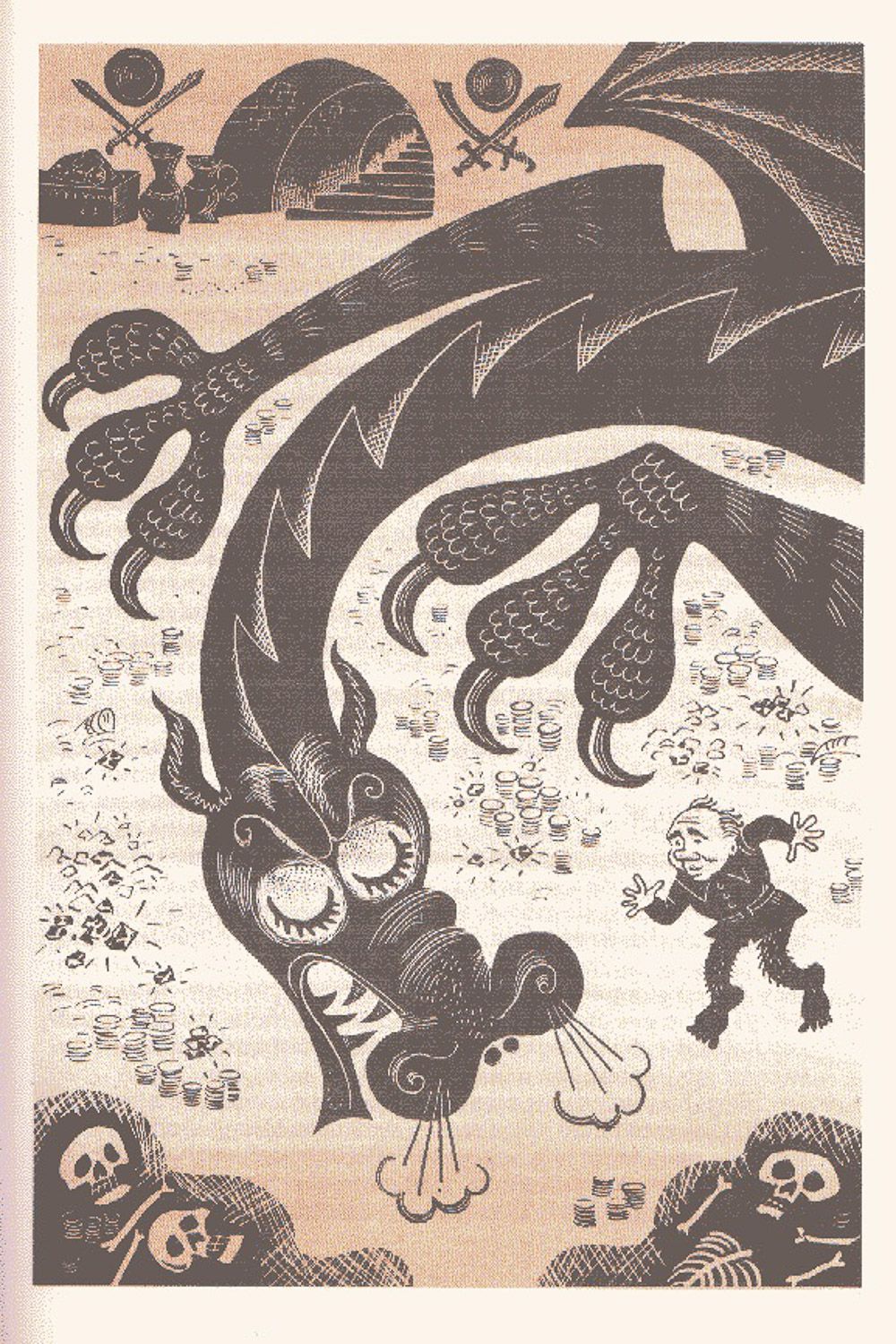

As with many Russian translations during the Cold War, the book came with a completely different set of illustrations. Mine, I remember regretting slightly, lacked pictures altogether. A friend’s edition, however, was illustrated in the typical Russian style: much more traditionally stylized than Tolkien’s own drawings, they were more angular, friendlier, almost cartoonish.

In this post, we include a number of these images from the 1976 printing. The cover, above, depicts a grinning Bilbo Baggins holding a gem. Below, Gandalf, an ostensibly harmless soul, pays Bilbo a visit.

Next, we have the three trolls, arguing about their various eating arrangements, with Bilbo hiding to the side.

Here, Gollum, née Smeagol, paddles his raft in the depths of the mountains.

Finally, here’s Bilbo, fulfilling his role as a burglar in Smaug’s lair.

For more of the Soviet illustrations of The Hobbit, head on over to Mashable.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in March, 2015

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related Content:

Download a Free Course on The Hobbit by “The Tolkien Professor,” Corey Olsen

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

The Only Drawing from Maurice Sendak’s Short-Lived Attempt to Illustrate The Hobbit