Some may find her insufferable, but most readers adore her: the insouciant little pig Olivia—New Yorker, art lover, and Caldecott Medal winner—has forever embedded herself in children’s literary culture as an archetype of childhood curiosity and self-confidence, especially in scenes like that of the first book of the series, in which the fearless piglet produces her own drip painting on the wall of the family’s Upper East Side apartment after puzzling over Jackson Pollock’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Olivia also admires Degas, aspires to the ballet, and dreams of being Maria Callas.)

Olivia’s headstrong challenge to Pollock is infectious, and enacts a notion common among amateur viewers of Abstract Expressionism—“I could do that.” Her “Jackson Piglet Wall Painting” features in a book that gives children their own set of instructions for making a pseudo-Pollock (on paper, of course). As you will see, however, in the video above—a guide for grown-ups who may wish to do the same—Pollock’s process is not so easily duplicated, and cannot be done on the wall. As the Ed Harris-starring biopic dramatized, Pollock made his huge canvasses on the floor—drawing the lines and gestural figures in the air rather than on the canvas.

In these videos from the Museum of Modern Art’s upcoming free online course on Postwar painting, educator and independent conservator Corey D’Augustine demonstrates that, we can, with some degree of stamina and athleticism, approximate Pollock’s technique. We cannot, however, recreate his temperament and emotional state. And, as viewers of the film based on his life will know, we would not want to. Pollock was a violently abusive, depressive alcoholic, and while there may be no necessary relation to creativity and suffering, New York Abstract Expressionists seemed to wrest the intensity of their work from wells of personal pain.

It is no wonder that the longest video in D’Augustine’s series covers the methods of Agnes Martin. The enigmatic Martin used her work as a discipline that took her beyond despair and defeat. Like Gertrude Stein or Samuel Beckett, she insisted that art, though a form of self-expression, must emerge impersonally, such that the artist “can take no credit for its sudden appearance.” On the other side of failure—she told her audience in a poignant and powerful 1973 speech called “On the Perfection Underlying Life”—“we still go on without hope or desire or dreams or anything. Just going on with almost no memory of having done anything.”

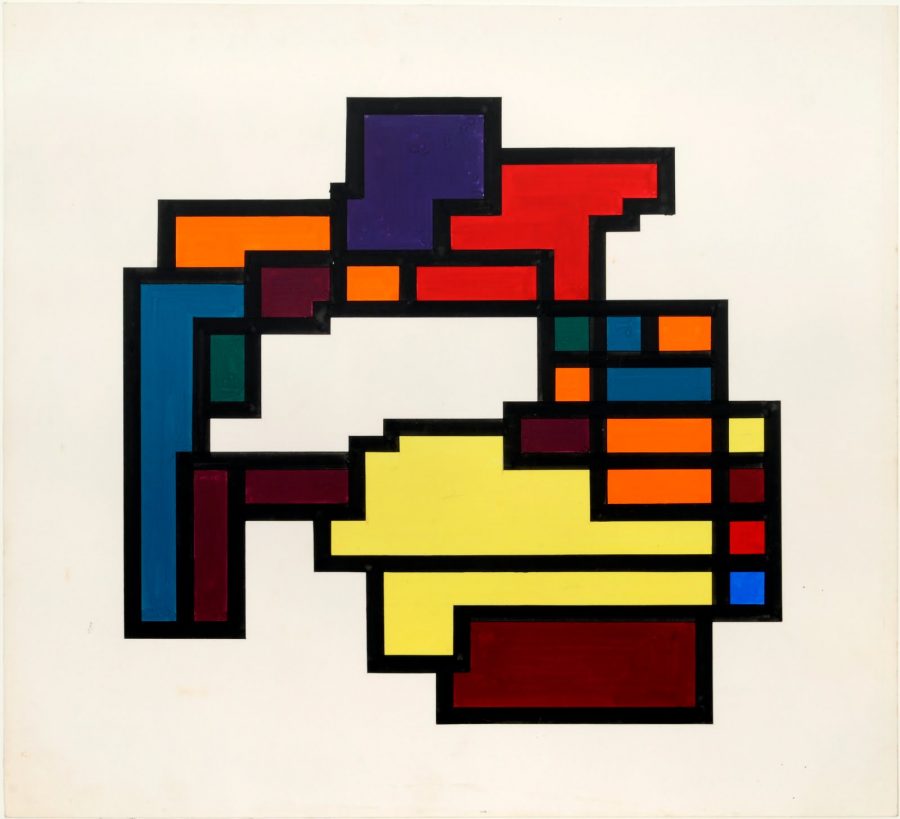

The attitude, Martin said, is a discipline, the discipline of art—one that saw her through a lifelong struggle with schizophrenia. Inspired by Taoism and Zen Buddhism, Martin’s “luminous, silent” paintings are studies in patience and deliberation. We see a very different technique in the gestural painting of Willem de Kooning—another Abstract Expressionist with a serious drinking problem. Do these biographical issues matter? While it may do Martin’s work a disservice to reduce it to “the products of a person compelled by mental illness,” as Zoe Pilger writes at The Independent, de Kooning’s eventual sobriety led to a “dramatic shift,” Susan Cheever notes, “in the way he saw and painted the world in his last decade or so.”

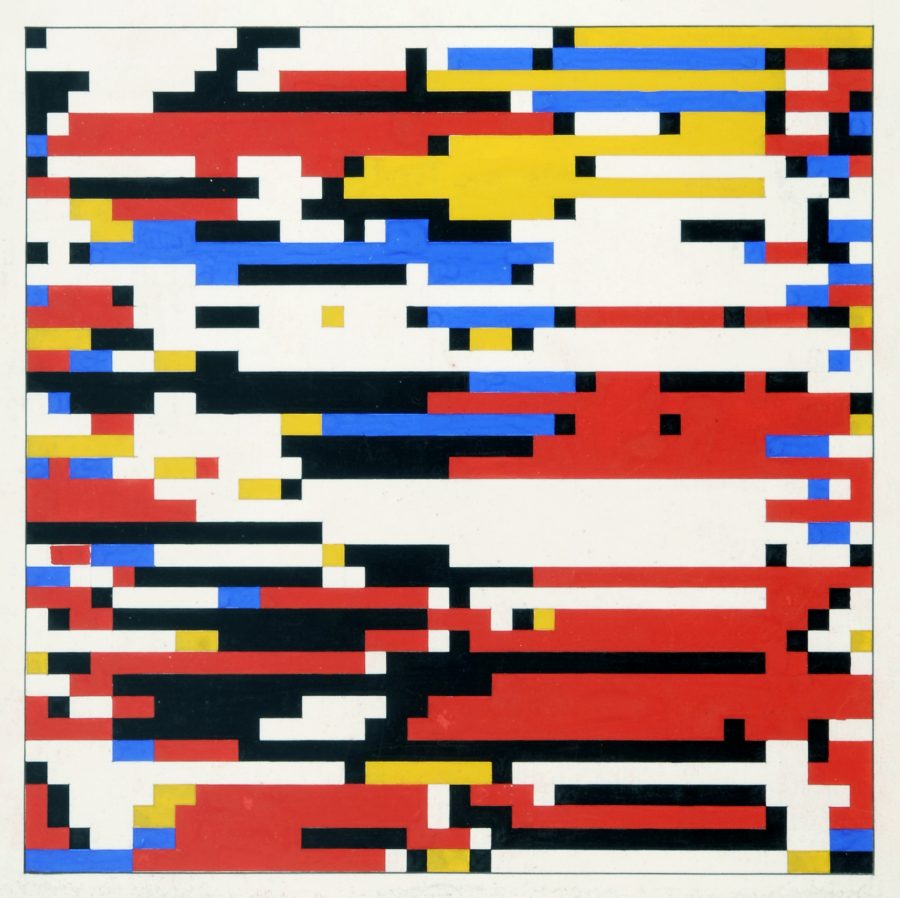

We need not psychologize the work of any of these artists, including that of the bipolar Mark Rothko, above, to learn from their techniques. And yet it remains the case that—even were we to duplicate Pollock, Martin, de Kooning, or Rothko on canvas, we would never be able to imbue it with their peculiar personalities, pains, and movements, with the depth and intensity each artist brought to their work. Great art does not require suffering, but many artists have poured their suffering into art that only they could make.

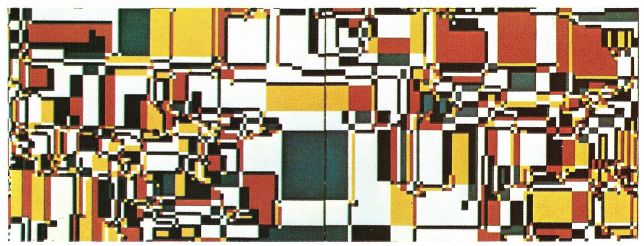

But mimicry is not the goal of MoMA’s class. Instead “In the Studio: Postwar Abstract Painting” intends to give students “a deeper understanding of what a studio practice means and how ideas develop from close looking. They’ll also “gain a sensitivity to the physical qualities of paint,” a key feature of this material and texture-obsessed group, and the course will examine the “broader cultural, intellectual, and historical context about the decades after World War II, when these artists were active.”

The eight-week course covers seven artists, including those above and Ad Reinhardt, Yayoi Kusama, and Barnett Newman. Students are free to do quizzes and written assignments only, or to participate in the optional studio exercises, provided they have the space and the materials. (For those studio practitioners, D’Augustine offers brief tutorials on tools like the palette knife and materials like stains.) Watch the trailer for D’Augustine’s course above. Like the irrepressible Olivia, students will be encouraged “to experiment quite wildly” with what they might learn.

“In the Studio: Postwar Abstract Painting” has been added to our list, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

Jackson Pollock 51: Short Film Captures the Painter Creating Abstract Expressionist Art

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

MoMA Puts Pollock, Rothko & de Kooning on Your iPad

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness