Jean Cocteau was a great many things to a great many people—writer, filmmaker, painter, friend, and lover. In the latter two categories he could count among his acquaintances such modernist giants as Pablo Picasso, Kenneth Anger, Erik Satie, Marlene Dietrich, Edith Piaf, Jean Marais, Marcel Proust, André Gide, and a number of other famous names. But Cocteau himself had little use for fame and its blandishments. As you’ll see in the short film above, “Cocteau Addresses the Year 2000,” the great 20th century artist considered the many awards bestowed upon him naught but “transcendent punishment.” What Cocteau cared for most was poetry; for him it was the “basis of all art, a ‘religion without hope.’ ”

Cocteau began his career as a poet, publishing his first collection, Aladdin’s Lamp, at the age of 19. By 1963, at the age of 73, he had lived one of the richest artistic lives imaginable, transforming every genre he touched.

Deciding to leave one last artifact to posterity, Cocteau sat down and recorded the film above, a message to the year 2000, intending it as a time capsule only to be opened in that year (though it was discovered, and viewed a few years earlier). Biographer James S. Williams describes the documentary testament as “Cocteau’s final gift to his fellow human beings.”

He reiterates some of his long-standing artistic themes and principles: death is a form of life; poetry is beyond time and a kind of superior mathematics; we are all a procession of others who inhabit us; errors are the true expression of an individual, and so on. The tone is at once speculative and uncompromising…

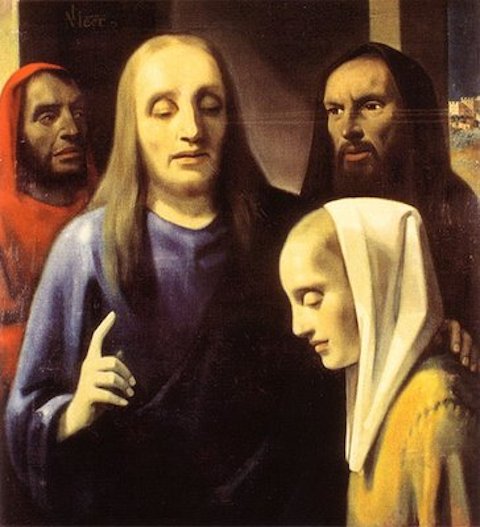

Portraying himself as “a living anachronism” in a “phantom-like state,” Cocteau, seated before his own artwork, quotes St. Augustine, makes parables of events in his life, and addresses, primarily, the youth of the future. The uses and misuses of technology comprise a central theme of his discourse: “I certainly hope that you have not become robots,” Cocteau says, “but on the contrary that you have become very humanized: that’s my hope.” The people of his time, he claims, “remain apprentice robots.”

Among Cocteau’s concerns is the dominance of an “architectural Esperanto, which remains our time’s great mistake.” By this phrase he means that “the same house is being built everywhere and no attention is paid to climate, atmospherical conditions or landscape.” Whether we take this as a literal statement or a metaphor for social engineering, or both, Cocteau sees the condition as one in which these monotonous repeating houses are “prisons which lock you up or barracks which fence you in.” The modern condition, as he frames it, is one “straddling contradictions” between humanity and machinery. Nonetheless, he is impressed with scientific advancement, a realm of “men who do extraordinary things.”

And yet, “the real man of genius,” for Cocteau, is the poet, and he hopes for us that the genius of poetry “hasn’t become something like a shameful and contagious sickness against which you wish to be immunized.” He has very much more of interest to communicate, about his own time, and his hopes for ours. Cocteau recorded this transmission from the past in August of 1963. On October 11 of that same year, he died of a heart attack, supposedly shocked to death by news of his friend Edith Piaf’s death that same day in the same manner.

His final film, and final communication to a public yet to be born, accords with one of the great themes of his life’s work—“the tug of war between the old and the new and the paradoxical disparities that surface because of that tension.” Should we attend to his messages to our time, we may find that he anticipated many of our 21st century dilemmas between technology and humanity, and between history and myth. It’s interesting to imagine how we might describe our own age to a later generation, and, like Cocteau, what we might hope for them.

via Network Awesome

Related Content:

Jean Cocteau’s Avante-Garde Film From 1930, The Blood of a Poet

The Postcards That Picasso Illustrated and Sent to Jean Cocteau, Apollinaire & Gertrude Stein

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness