Are we truly in the midst of a human-caused sixth mass extinction, an era of “biological annihilation”? Many scientists and popular science writers say yes, using terms like “Holocene” or “Anthropocene” to describe what follows the Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic, and Cretaceous periods. Peter Brannen, the author of extinction history The Ends of the Earth has found at least one scientist who thinks the concept is “junk.” But Brannen quotes some alarming statistics. Chilling, even. “Until very recently,” he writes, “all vertebrate life on the planet was wildlife. But astoundingly, today wildlife accounts for only 3 percent of Earth’s land animals; human beings, our livestock, and our pets take up the remaining 97 percent of the biomass… almost half of the Earth’s land has been converted into farmland.”

This state of affairs does not bode well for the millions of remaining species getting edged out of their environments by agribusiness and climate change. We learn from extinctions past that the planet rebounds after unimaginable catastrophe. Life really does go on, though it may take millions of years to recover. But the current forms of life may disappear before their time. If we want to understand what is at stake besides our own fragile fossil-fuel-based civilizations, we need to connect to life emotionally as well as intellectually. Short of globe-hopping physical immersion in the Earth’s biodiversity, we could hardly do better than immersing ourselves in the tradition of naturalist writing, art, and photography that brings the world to us.

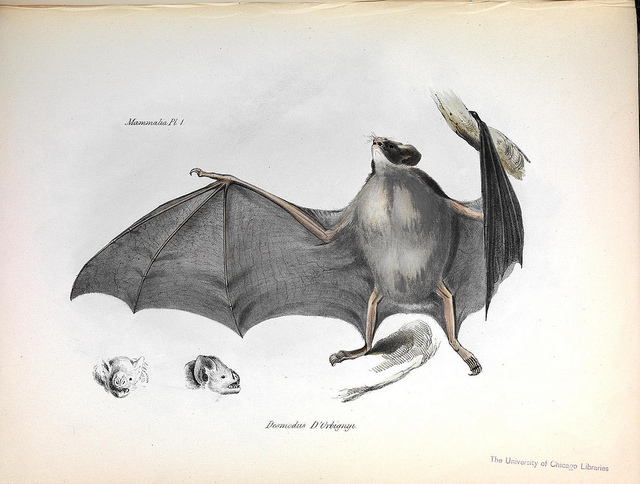

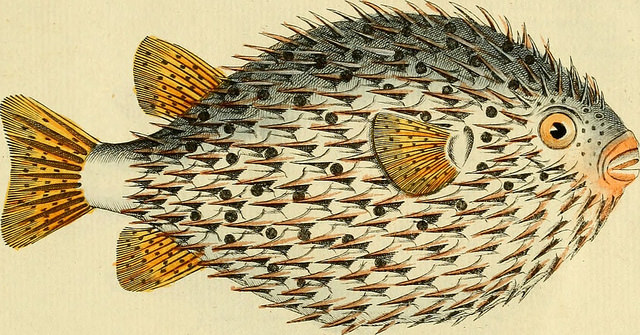

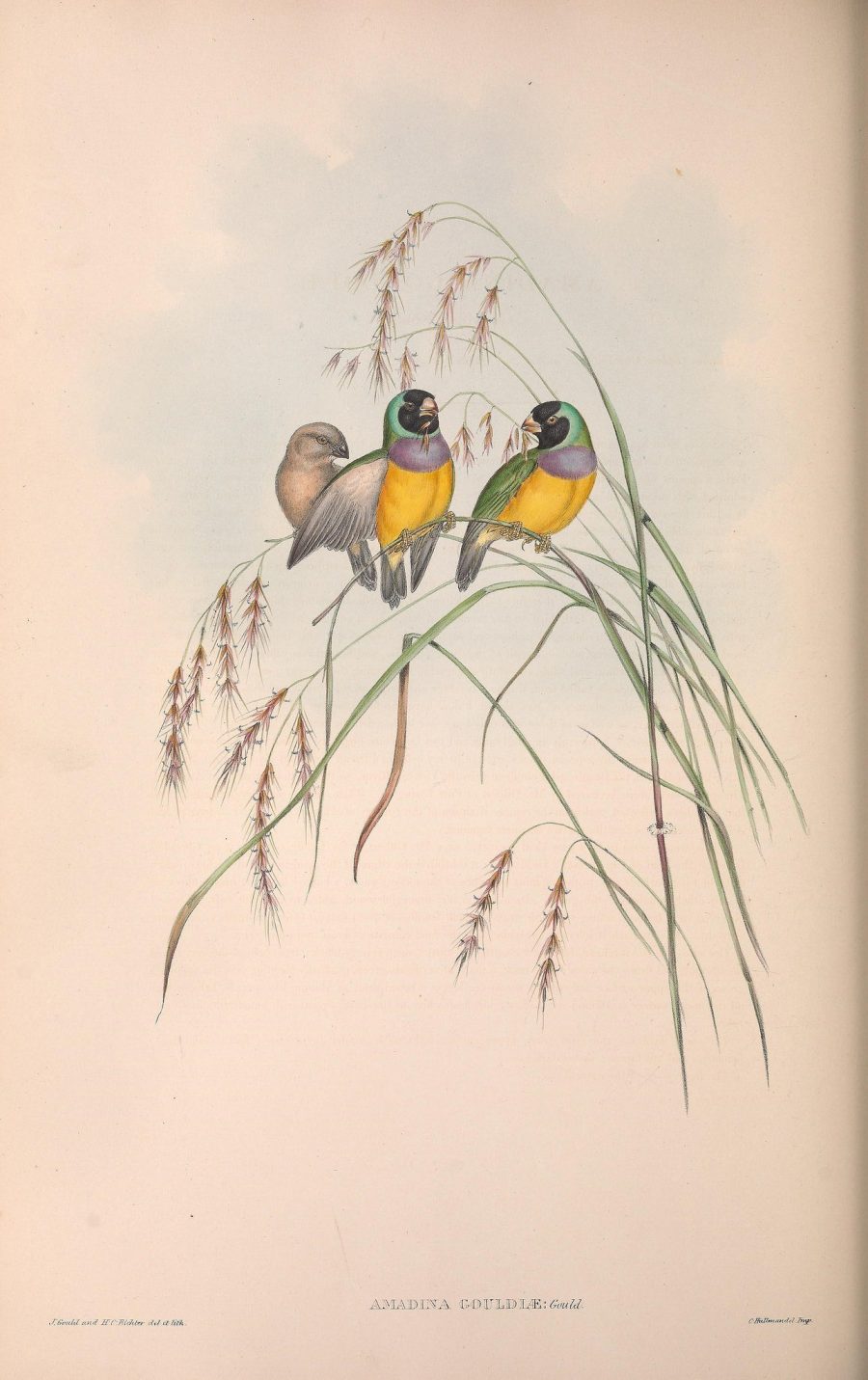

The Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), an “open access digital library for biodiversity literature and archives,” has for many years been making it easy for people to connect to nature through nature writing and illustration. On Flickr, you can find 319,000 carefully curated images. The collection itself is subdivided into different photo albums drawn from historical publications. For example, The Freshwater Fishes of the British Isles (1911), The Bird (1869), and The Insect Book (1901).

This image archive offers expansive views of humanity’s encounter with the natural world, not only through statistics and academic jargon, but through the artistic recording of wonder, scientific curiosity, and deep appreciation. Enter the archive here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

Watch 50 Hours of Nature Soundscapes from the BBC: Scientifically Proven to Ease Stress and

The Meticulous, Elegant Illustrations of the Nature Observed in England’s Countryside

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.