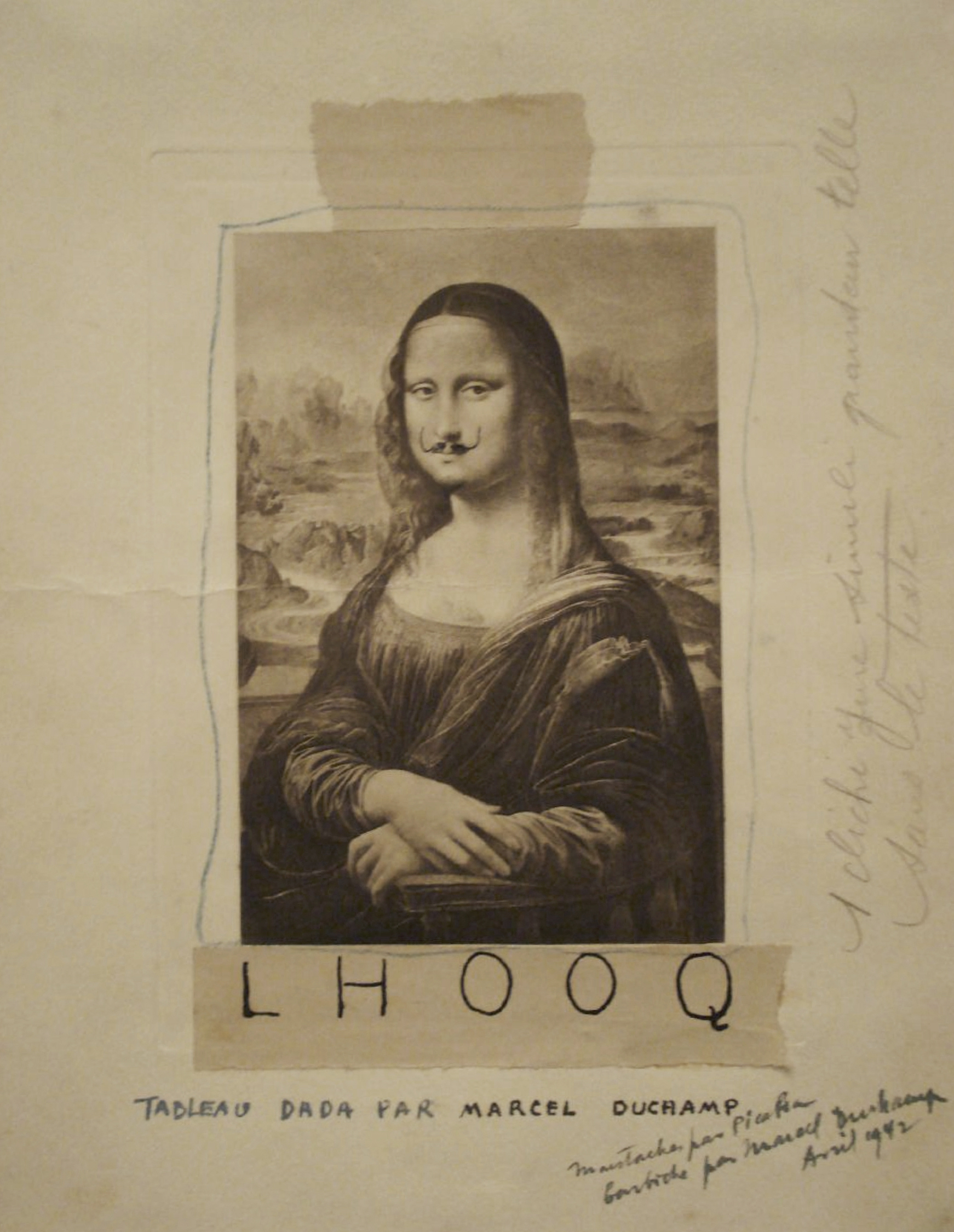

Practically anyone could take one glance at Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and identify it as a Picasso, even if they’ve never seen it before and couldn’t say anything else about it. That alone goes some way to explaining why the painting would end up ranked as the most important artwork of the twentieth century, at least according to a study by University of Chicago economist David W. Galenson. For that title it beat out the likes of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, Richard Hamilton’s Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain and Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, and Picasso’s own Guernica.

With Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Galenson writes, “the greatest artist of the century initiated the century’s most important artistic movement. Art scholars debate whether the Demoiselles should be considered a Cubist painting, but there is no question that it differed profoundly from all of the art that preceded it, and that it began the development of Cubism.”

Painted in ambitious response to Henri Matisse’s Le Bonheur de vivre, its rejection of traditional formality and beauty shocked even Picasso’s forward-thinking colleagues: “Not only did Matisse denounce the painting as an attempt to discredit modern art, but even Georges Braque, who would later join forces with Picasso in developing Cubism, was initially so shocked by the painting that he compared Picasso to the fairground fire-eaters who drank kerosene to spit flames.”

Of course, there was also the matter of the painting’s subject, five nude prostitutes in a Barcelona brothel. But as explained by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker in the Smarthistory video above, the Demoiselles wasn’t always about the demoiselles alone. “In the original sketches, the women were focusing on a male that was included, a sailor,” says Zucker. “There was also a medical student.” At some stages, Harris emphasizes, the latter carried a human skull, a piece of professional equipment but also “a reminder of death, a memento mori. And so there seems to be some tension here between the sensuality that the sailor is indulging in and a moralizing reminder that the pleasures of life are short”: an unusual perspective to be expressed by a 26-year-old, but then, Picasso wasn’t the usual artist.

Related Content:

Pablo Picasso’s Childhood Paintings: Precocious Works Painted Between the Ages of 8 and 15

Thousands of Pablo Picasso’s Works Now Available in a New Digital Archive

How to Understand a Picasso Painting: A Video Primer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.