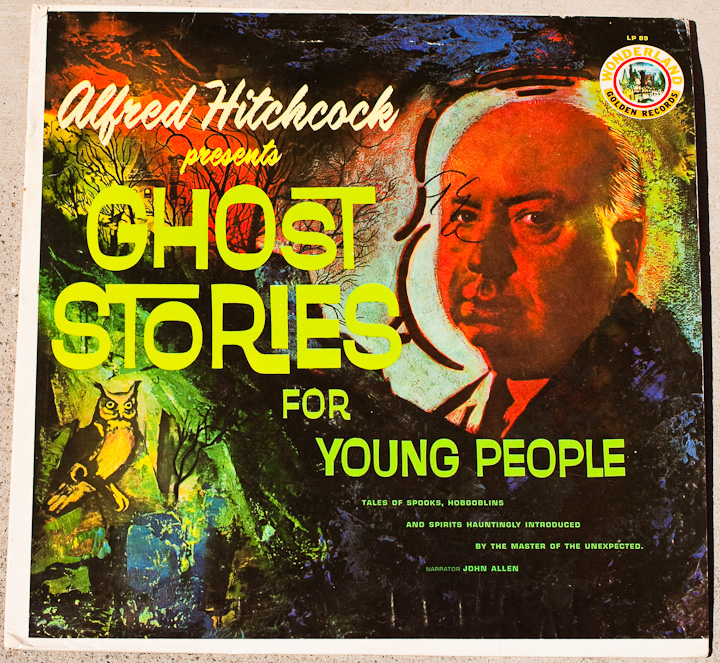

“Now of course, the best way to listen to ghost stories is with the lights out,” says the inimitable Alfred Hitchcock, as he introduces his 1962 vinyl release Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Ghost Stories for Young People. “There is nothing like a dark room to attract ghosts and you may like to have some of our mutual friends come and listen with you.”

Just in time for Halloween, we are shining a flickering light on this album, released once before on CD and now on Spotify. (You can also find it on YouTube.) It will either take listeners back to when they were kids, or frighten a new generation of young ones for the first time.

Though Hitchcock’s films toyed with spirits-—Rebecca and Vertigo among them-—he never really made straight up monster movies or ghost stories. (Psycho and The Birds are the closest he ever got.) But once he became a television host and personality in the 1950s, his mischievous character and his macabre voice made him a natural to present all sorts of ghoulish anthologies, resulting in numerous paperbacks and hardbacks, most of which he had little to do with but simply bore his name as a stamp of frightening authority.

And even before that, Hitchcock was putting his name to short suspense story collections, and a mystery magazine that was started in 1956 and continues to this day. We talk about him as one of the best film directors of all time, but he was also a one-man suspense and terror industry in his day, a canny creator who knew the worth of licensing his name.

Of the six stories here, the two given writer’s credit are “Jimmy Takes Vanishing Lessons” by Walter R. Brooks (a children’s author who created the talking horse character Mr. Ed) and “The Open Window” by Edwardian writer Saki.

Judging from the YouTube comments for the crackly recording posted there, these stories have haunted these listeners since their childhood. Kids these days might prefer a dish of creepypasta, but there’s no denying the power of a voice, creepy music, and sudden sound effects, all delivered by way of headphones…with the lights off.

Related Content:

Stephen King’s Top 10 All-Time Favorite Books

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rules for Watching Psycho (1960)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.