“Eastern medicine” and “Western medicine”—the distinction is a crude one, often used to misinform, mislead, or grind cultural axes rather than make substantive claims about different theories of the human organism. Thankfully, the medical establishment has largely given up demonizing or ignoring yogic and meditative mind-body practices, incorporating many of them into contemporary pain relief, mental health care, and preventative and rehabilitative treatments.

Hindu and Buddhist critics may find much not to like in the secular appropriation of practices like mindfulness and yoga, and they may find it odd that such a fundamental insight as the relationship between mind and body should ever have been in doubt. But we know from even a slight familiarity with European philosophy (“I think, therefore I am”) that it was from the Enlightenment into the 20th century.

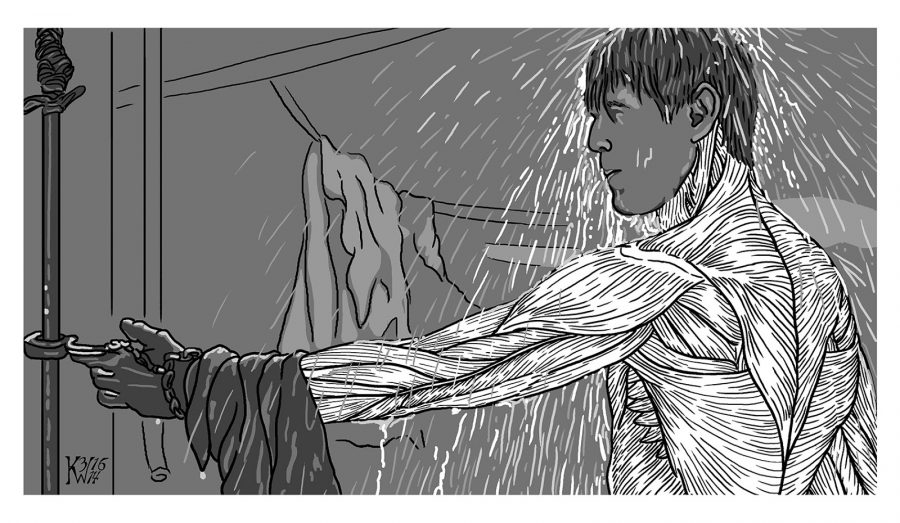

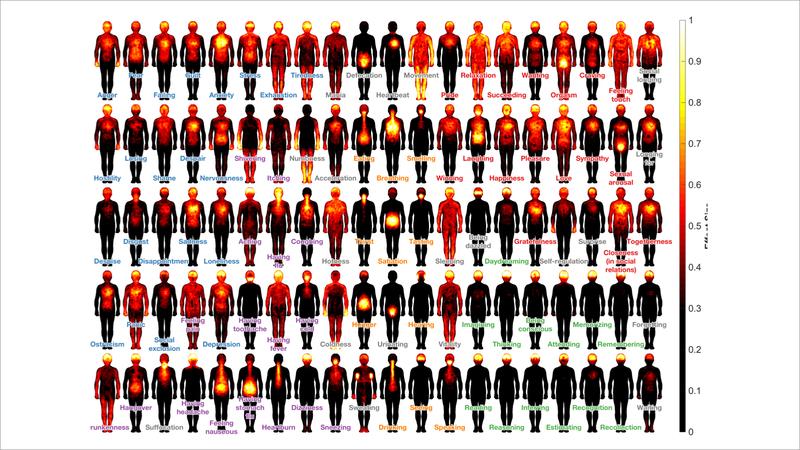

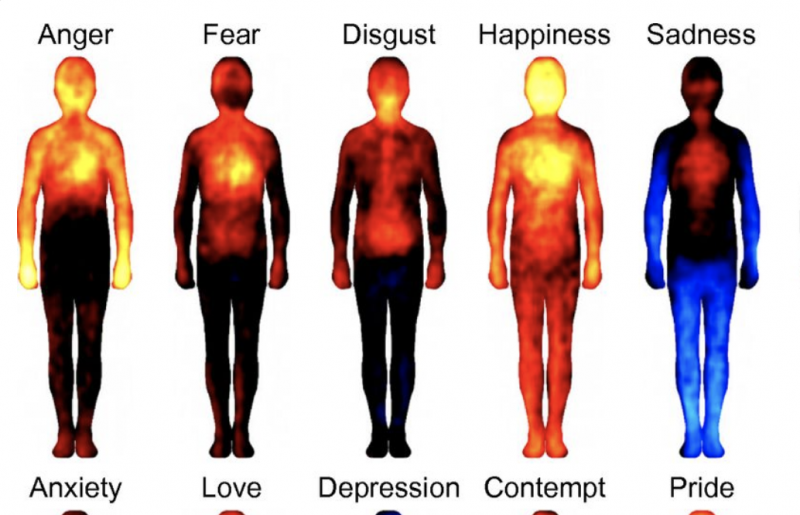

Now, says Riitta Hari, co-author of a 2014 Finish study on the bodily locations of emotion, “We have obtained solid evidence that shows the body is involved in all types of cognitive and emotional functions. In other words, the human mind is strongly embodied.” We are not brains in vats. All those colorful old expressions—“cold feet,” “butterflies in the stomach,” “chill up my spine”—named qualitative data, just a handful of the embodied emotions mapped by neuroscientist Lauri Nummenmaa and co-authors Riitta Hari, Enrico Glerean, and Jari K. Hietanen.

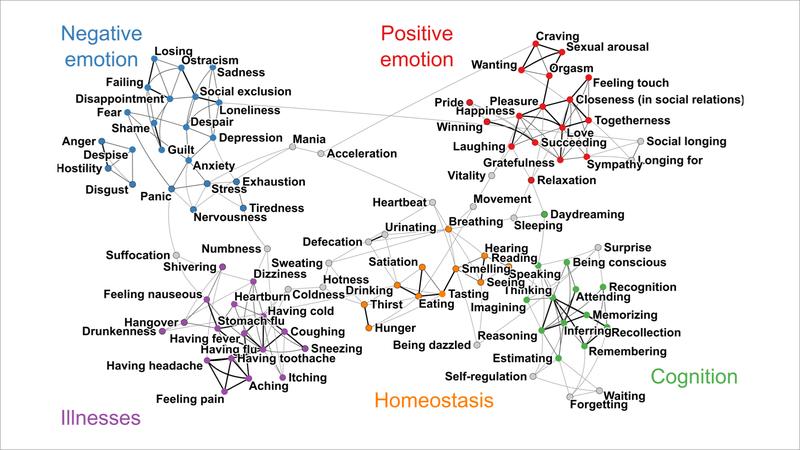

In their study, the researchers “recruited more than 1,000 participants” for three experiments, reports Ashley Hamer at Curiosity. These included having people “rate how much they experience each feeling in their body vs. in their mind, how good each one feels, and how much they can control it.” Participants were also asked to sort their feelings, producing “five clusters: positive feelings, negative feelings, cognitive processes, somatic (or bodily) states and illnesses, and homeostatic states (bodily functions).”

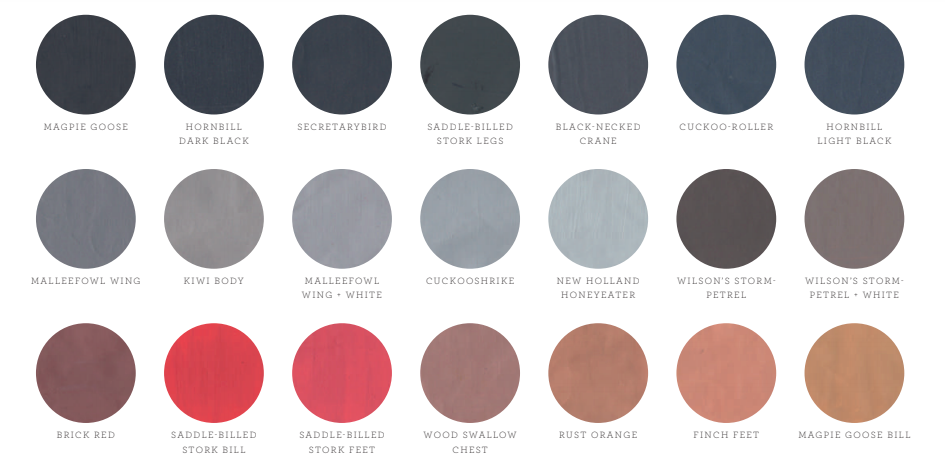

After making careful distinctions between not only emotional states, but also between thinking and sensation, the study participants colored blank outlines of the human body on a computer when asked where they felt specific feelings. As the video above from the American Museum of Natural History explains, the researchers “used stories, video, and pictures to provoke emotional responses,” which registered onscreen as warmer or cooler colors.

Similar kinds of emotions clustered in similar places, with anger, fear, and disgust concentrating in the upper body, around the organs and muscles that most react to such feelings. But “others were far more surprising, even if they made sense intuitively,” writes Hamer “The positive emotions of gratefulness and togetherness and the negative emotions of guilt and despair all looked remarkably similar, with feelings mapped primarily in the heart, followed by the head and stomach. Mania and exhaustion, another two opposing emotions, were both felt all over the body.”

The researchers controlled for differences in figurative expressions (i.e. “heartache”) across two languages, Swedish and Finnish. They also make reference to other mind-body theories, such as using “somatosensory feedback… to trigger conscious emotional experiences” and the idea that “we understand others’ emotions by simulating them in our own bodies.” Read the full, and fully illustrated, study results in “Bodily Maps of Emotions,” published by the National Academy of Sciences.

Related Content:

How Meditation Can Change Your Brain: The Neuroscience of Buddhist Practice

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness