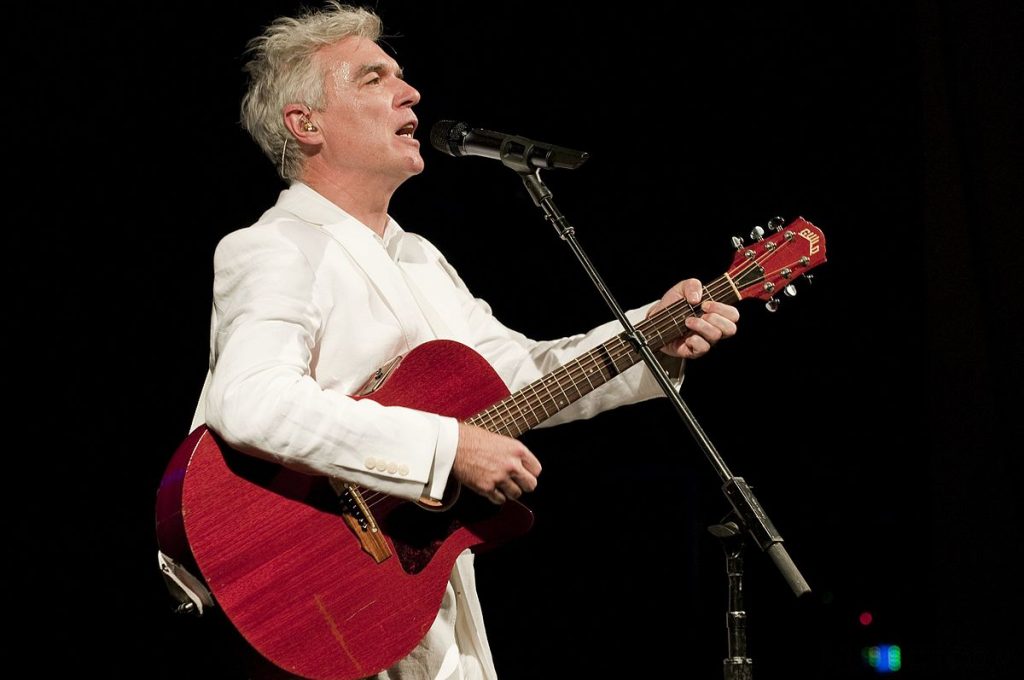

Image by LivePict, via Wikimedia Commons

The meaning of the word “library” has never been more ambiguous. When we can virtually carry library-sized collections of images, music, literature and reference data in our pockets, what are physical libraries but museums of a sort? Of course, from the point of view of librarians especially, this isn’t true in the least. Libraries are fortresses of free speech, public education, and “information literacy” at the community level. Rather than obsolete or secondary, they may be more necessary than ever.

On a larger view both of these things are true. For millions of people, physical libraries have become secondary and will remain so, but they also remain community resources of paramount importance. As Ted Mills posted here in the summer of 2015, Talking Heads frontman, “polymath and all-around swell person David Byrne” affirmed that latter status of the physical library when he leant out 250 books on music from his personal library to themselves be leant out at a library hosted by the 22nd annual Meltdown Festival and London’s Poetry Library.

“I love a library,” wrote Byre in his own Guardian essay announcing the project.

I grew up in suburban Baltimore and the suburbs were not a particularly cosmopolitan place. We were desperate to know what was going on in the cool places, and, given some suggestions and direction, the library was one place where that wider exciting world became available. In my little town, the library also had vinyl that one could check out and I discovered avant-garde composers such as Xenakis and Messiaen, folk music from various parts of the world and even some pop records that weren’t getting much radio play in Baltimore. It was truly a formative place.

Having grown up in the DC suburbs in the years before the internet, I can relate, and would add the importance of local music stores and affordable all-age venues. But Byrne has never stayed tied to the media of his youth. During his several decades as a cultural critic and arts educator, he has made ecumenical use of mundane new technologies to interrogate the status of other older forms. One recent project, for example, consisted of a 96-page book and 20-minute DVD about his experiments in PowerPoint art. One of the questions raised by the project, writes Veronique Vienne, is whether the book is “an antiquated cultural artifact” in an age of hypervisualization.

Clearly for Byrne himself, the answer is no, and that answer is closely connected to the question of commodification verses open access, whether through libraries or free online archives. “The idea of reading books for free,” he writes, “didn’t kill the publishing business, on the contrary, it created nations of literate and passionate readers. Shared interests and the impulse to create.” Byrne’s library reflects a lifetime of shared interests and creative inspiration. He himself has spent his life writing about music in spite of the clever maxim that such a venture is like “dancing about architecture.” It is, he writes, “stimulating and inspiring nonetheless.”

In the spirit of sharing information and championing libraries, Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova published a list of nearly all of the titles in Byrne’s lending library, with links to public library editions near you through WorldCat. Find the full list below, courtesy of David Byrne’s site, and see Brain Picking’s list and short essay here.

1. 40 Watts from Nowhere: A Journey into Pirate Radio by Sue Carpenter

2. A divina comedia dos Mutantes by Carlos Calado

3. A Photographic Record: 1969–1980 by Mick Rock

4. A Thelonious Monk: Study Album by Lionel Grigson

5. A Whole Room for Music: A Short Guide to the Balfour Building Music Makers’ Gallery by Helene La Rue

6. Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life by Brandon Labelle

7. Acoustics for Radio and Television Studios by Christopher Gilford

8. Africa Dances by Geoffrey Gorer

9. African Music: A People’s Art by Francis Bebey

10. African Rhythm and African Sensibility by John Miller Chernoff

11. Afro-American Folk Songs by H.E. Krehbiel

12. AfroPop! An Illustrated Guide to Contemporary African Music by Sean Barlow & Banning Eyre

13. All You Need to Know About the Music Business by Donald S. Passman

14. Aloud: Voices from the Nuyorican Poets Cafè by Miguel Algarin & Bob Holman

15. An Illustrated Treasury of Songs by National Gallery of Art

16. And They All Sang: Adventures of an Eclectic Disc Jockey by Studs Terkel

17. Arranged Marriage by Wallace Berman & Robert Watts

18. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music by Cristoph Cox & Daniel Warner

19. Austin City Limits: 35 Years in Photographs by Scott Newton & Terry Lickona

20. Bachata: A Social History of a Dominican Popular Music by Deborah Pacini Hernandez

21. Bandalism: The Rock Group Survival Guide by Julian Ridgway

22. Beats of the Heart: Popular Music of the World by Jeremy Marre & Hannah Charlton

23. Best Music Writing 2001 by Nick Hornby & Ben Schafer

24. Best Music Writing 2002 by Jonathan Lethem & Paul Bresnick

25. Best Music Writing 2003 by Matt Groening & Paul Bresnick

26. Best Music Writing 2006 by Mary Gaitskill & Daphne Carr

27. Best Music Writing 2007 by Robert Christgau & Daphne Carr

28. Bicycle Diaries by David Byrne

29. Black Music of Two Worlds by John Storm Roberts

30. Black Rhythms of Peru: Reviving African Musical Heritage in the Black Pacific by Heidi Carolyn Feidman

31. Blues Guitar: The Men Who Made the Music by Jas Obrecht

32. Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music that Seduced the World by Ruy Castro

33. Botsford Collection of Folk Songs Volume 1 by Florence Hudson Botsford

34. Botsford Collection of Folk Songs Volume 2 by Florence Hudson Botsford

35. Bound for Glory by Woody Guthrie

36. Bourbon Street Black: The New Orleans Black Jazzman by Jack V Buerkle & Danny Barker

37. Brazilian Popular Music and Citizenship by Idelber Avelar & Christopher Dunn

38. Brutality Garden: Tropicalla and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture by Christopher Dunn

39. Bug Music: How Insects Gave Us Rhythm and Noise by David Rothenberg

40. But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz by Geoff Dyer

41. Cancioneiro Vinicius De Moraes by Orfeu

42. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music by Mark Katz

43. Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley by Timothy White

44. Chambers by Alvin Lucier & Douglas Simon

45. Chinaberry Sidewalks: A Memoir by Rodney Crowell

46. Chris Stein/Negative: Me, Blondie and the Advent of Punk by Deborah Harry, Glenn O’Brien & Shepard Fairey

47. Clandestino: In Search of Manu Chao by Peter Culshaw

48. Clothes Music Boys by Viv Albertine

49. Cocinando! Fifty Years of Latin Cover Art by Pablo Yglesias

50. Conjunto by John Dyer

51. Conversations with Glenn Gould by Jonathan Cott

52. Conversing with Cage by Richard Kostelanetz

53. Copyrights & Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How it Threatens Creativity by Siva Vaidhyanathan

54. Dancing in Your Head: Jazz, Blues, Rock and Beyond by Gene Santoro

55. Desert Plants: Conversations with Twenty-Three American Musicians by Walter Zimmerman

56. Diccionario de Jazz Latino by Nat Chediak

57. Diccionario del Rock Latino by Nat Chediak

58. Driving Through Cuba: Rare Encounters in the Land of Sugar Cane and Revolution by Carlo Gebler

59. Drumming at the Edge of Magic: A Journey into the Spirit of Percussion by Mickey Hart & Jay Stevens

60. Essays on Music by Theodor W. Adorno

61. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond by Michael Nyman

62. Fair Use: The Story of the Letter U and the Numeral 2 by Negativland

63. Fela Fela: This Bitch of a Life by Carlos Moore

64. Fetish & Fame: The 1997 MTV Video Music Awards by David Felton

65. Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes by Stephen Sondheim

66. Folk and Traditional Music of the Western Continents by Bruno Nettl

67. Folk Song Style and Culture by Alan Lomax

68. Folk: The Essential Album Guide by Neal Walers & Brian Mansfield

69. Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition by Iannis Xenakis

70. Fotografie in Musica by Guido Harari

71. Genesis of a Music by Harry Partch

72. Give my Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman by B.H. Friedman

73. Gravikords, Whirlies, & Pyrophones: Experimental Musical Instruments by Bart Hopkin

74. Guia Esencial De La Salsa by Jose Manuel Gomez

75. Guitar Zero: The New Musician and the Science of Learning by Gary Marcus

77. Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listening, and Modernity by Veit Erlmann

78. Here Come the Regulars: How to Run a Record Label on a Shoestring Budget by Ian Anderson

79. He Stopped Loving Her Today: George Jones, Billy Sherrill and the Pretty-Much Totally True Story of the Making of the Greatest Country Record of All Time by Jack Isenhour

80. Hip Hop: The Illustrated History of Break Dancing, Rap Music and Graffiti by Steven Hager

81. Hit Men by Frederic Dannen

82. Hitsville: The 100 Greatest Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazines 1954–1968 by Alan Betrock

83. Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From and Why by Ellen Dissanayake

84. Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture by Alice Echols

85. How Music Works: The Science and Psychology of Beautiful Sounds, from Beethoven to the Beatles and Beyond by John Powell

86. Hungry for Heaven: Rock and Roll and the Search for Redemption by Steve Turner

87. I Have Seen the End of the World and it Looks Like This by Bob Schneider

88. I’ll Take You There Mavis Staples: The Staple Songers, and the March Up Freedom’s Highway by Greg Kot

89. In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise by George Prochnik

90. Indian Music by B. Chaitanya Deva

91. It Ain’t Easy: Long John Baldry and the Birth of the British Blues by Paul Myers

92. Japanese Music and Musical Instruments by William P. Malm

93. Javanese Gamelan by Jennifer Lindsay

94. Jazz by William Claxton

95. Knitting Music by Michael Dorf

96. La Traviata: In Full Score by Giuseppe Verdi

97. Laurie Anderson by John Howell

98. Leon Geico: Cronica de un Sueno by Oscar Finkelstein

99. Lexicon of Musical Invective by Nicolas Slonimsky

101. Light Strings: Impressions of the Guitar by Ralph Gibson & Andy Summers

102. Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music by Eric Weisbard

103. Listening Through the Noise: the Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music by Joanna Demers

104. Listen to This by Alex Ross

105. Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981–2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany by Stephen Sondheim

106. Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Music Made New in New York City in the ’70s by Will Hermes

107. Love in Vain: The Life and Legend of Robert Johnson by Allen Greenberg

108. Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture by Tim Lawrence

109. Low by Hugo Wilcken

110. Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-dirty in Seventies New York by James Wolcott

111. Macumba: The Teachings of Maria-Jose, Mother of the Gods by Serge Bramly

112. Mango Mambo by Adal

113. Masters of Contemporary Brazilian Song: MPB 1965–1985 by Charles Perrone

114. Max’s Kansas City: Art, Glamour, Rock and Roll by Steven Kasher

115. Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride with Tommy James and the Shondells by Tommy James

116. Miles: The Autobiography by Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe

117. Mingering Mike: The Amazing Career of an imaginary Soul Superstar by Dori Hadar

118. Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and “Inventor of Jazz” by Alan Lomax

119. Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture by Thurston Moore

120. Music by Paul Bowles

121. Music and Communication by Terence McLaughlin

122. Music and Globalization: Critical Encounters by Bob W. White

123. Music and the Brain: Studies in the Neurology of Music by MacDonald Critchley & R. A. Henson

124. Music and the Mind by Anthony Storr

125. Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession by Gilbert Rouget

126. Music Cultures of the Pacific, The Near East, and Asia by William P. Malm

128. Music in Cuba by Alejo Carpentier

129. Music, Language and the Brain by Aniruddh D. Patel

130. Musica Cubana Del Areyto a la Nueva Trova by Dr. Cristobal Diaz Ayala

131. Musical Instruments of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia with More than 4,000 Original Drawings by Ruth Midgely

132. Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain by Oliver Sacks

133. My Music by Susan D Crafts, Daniel Cavicchi & Charles Keil

134. New York Noise: Art and Music from the New York Underground 1978–88 by Stuart Baker

135. Noise: A Human History of Sound & Listening by David Hendy

136. Noise: The Political Economy of Music by Jacques Attali

137. Notations by John Cage

138. Ocean of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds by David Toop

139. On Sonic Art by Trevor Wishart

140. Opera 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving the Opera by Fred Plotkin

141. Patronizing The Arts by Marjorie Garber

142. Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music by Greg Milner

143. Pet Shop Boys: Literally by Chris Heath

144. Popular Musics of the Non-Western World: An Introductory Survey by Peter Manuel

145. The Power of Music: Pioneering Discoveries in the Science of Song by Elena Mannes

146. Presenting Celia Cruz by Alexis Rodriguez-Duarte

147. Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung by Lester Bangs

148. Queens of Havana: The Amazing Adventures of the Legendary Anacaona, Cuba’s First All-Girl Dance Band by Alicia Castro

149. Recordando a Tito Puente: El Rey del Timbal by Steven Loza

150. Reflections on Macedonian Music: Past and Future by Dimitrije Buzarovski

151. Remembering the Future by Luciano Berio

152. Repeated Takes: A Short History of Recording Music and Its Effect on Music by Michael Chanan

153. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties by Ian Macdonald

154. Rhythm & Blues in New Orleans by John Broven

155. Rock ‘n’ Roll is Here to Pay: The History of Politics in the Music Industry by Steve Shapple & Reebee Garofalo

156. Rock Archives by Michael Ochs

157. Rock Images: 1970–1990 by Claude Gassian

158. Rock Lives: Profiles and Interviews by Timothy White

159. Salsa Guidebook for Piano & Ensemble by Rebeca Mauleon

160. Salsa: The Rhythm of Latin Music by Gerard Sheller

161. Salsiology: Afro-Cuban Music and the Evolution of Salsa in New York City by Vernon W. Boggs

162. Samba by Alma Guillermoprieto

163. Sonic Transports: New Frontiers in Our Music by Cole Gagne

164. Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear by Steve Goodman

165. Souled American: How Black Music Transformed White Culture by Kevin Phinney

166. Sounding New Media: Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture by Frances Dyson

167. Soundings by Neuberger Museum

168. South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous by John Broven

169. Spaces Speak, Are You Listening: Experiencing Aural Architecture by Barry Blesser & Linda-Ruth Salter

170. Spirit Rising: My Life, My Music by Angelique Kidjo

171. Starmaking Machinery: The Odyssey of an Album by Geoffrey Stokes

172. Stockhausen: Conversations with the Composer by Jonathan Cott

173. Stolen Moments: Conversations with Contemporary Musicians by Tom Schnabel

174. Stomping the Blues by Albert Murray

175. Tango: The Art History of Love by Robert Farris Thompson

176. Text-Sound Texts by Richard Kostelanetz

177. The ABCs of Rock by Melissa Duke Mooney

178. The Agony of Modern Music by Henry Pleasants

179. The Anthropology of Music by Alan P. Merriam

180. The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help by Amanda Palmer

181. The Beatles: Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn

182. The Book of Drugs: A Memoir by Mike Dougherty

183. The Brazilian Sounds: Samba, Bossa Nova, and the Popular Music of Brazil by Chris McGowan & Ricardo Pessanha

184. The Faber Book of Pop by Hanif Kureishi & Jon Savage

185. The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places by Bernie Krause

186. The Human Voice by Jean Cocteau

187. The Kachamba Brothers’ Band: A Study of Neo-Traditional Music in Malawi by Gerhard Kubik

188. The Last Holiday: A Memoir by Gil Scott-Heron

189. The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States by John Storm Roberts

190. The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock by Charles White

191. The Merge Records Companion: A Visual Discography of the First Twenty Years by Merge Records

192. The Music Instinct by Philip Ball

193. The Music of Brazil by David P. Appleby

194. The Mystery of Samba: Popular Music and the National Identity in Brazil by Hermano Vianna

195. The New Woman Poems: A Tribute to Mercedes Sosa by Nestor Rodriguez Lacoren

196. The Performer Prepares by Robert Caldwell

197. The Rational and Social Foundations of Music by Max Weber

198. The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl by Trevor Schoonmake

199. The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa by Evan Eisenberg

200. The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century by Alex Ross

201. The Rolling Stone Interviews: The 1980s by Various

202. The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice by Greil Marcus

203. The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World by Trevor Cox

204. The Sun and the Drum: African Roots in Jamaican Folk Tradition by Leonard Barrett

205. The Thinking Ear by R. Murray Schafer

206. The Traditional Music of Japan by Kishibe Shigeo

207. The Triumph of Music: The Rise of Composers, Musicians and Their Art by Tim Blanning

208. The Veil of Silence by Djura

209. The Wilco Book by Dan Nadel

210. This Business of Music: The Definitive Guide to the Music Industry by M. William Krasilovsky & Sidney Shemel

211. This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of Human Obsession by Daniel J. Levitin

212. Through Music to Self by Peter Michael Hamel

213. West African Rhythms for Drumset by Royal Hartigan

214. What Good are the Arts? by John Carey

215. White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960’s by Joe Boyd

216. Who Shot Rock & Roll: A Photographic History 1955–Present by Gail Buckland

218. Whose Music? A Sociology of Musical Languages by John Shepard, Phil Virden, Graham Vulliamy, Trevor Wishart

219. Why is This Country Dancing: A One-Man Samba to the Beat of Brazil by John Krich

220. Woody Guthrie: A Life by Joe Klein

221. The Rough Guide to World Music: Latin and North America, Caribbean, India, Asia, and Pacific: An A‑Z of the Music, Musicians and Discs by Simon Broughton & Mark Ellingham

222. The Rough Guide to World Music: Salsa to Soukous, Cajun to Calypso by Simon Broughton, Mark Ellingham, David Muddyman & Richard Trillo

223. World: The Essential Album Guide by Adam McGovern

224. Yakety Yak: The Midnight Confessions and Revelations of Thirty-Seven Rock Stars and Legends by Scott Cohen

Related Content:

David Byrne’s Personal Lending Library Is Now Open: 250 Books Ready to Be Checked Out

David Byrne: How Architecture Helped Music Evolve

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness