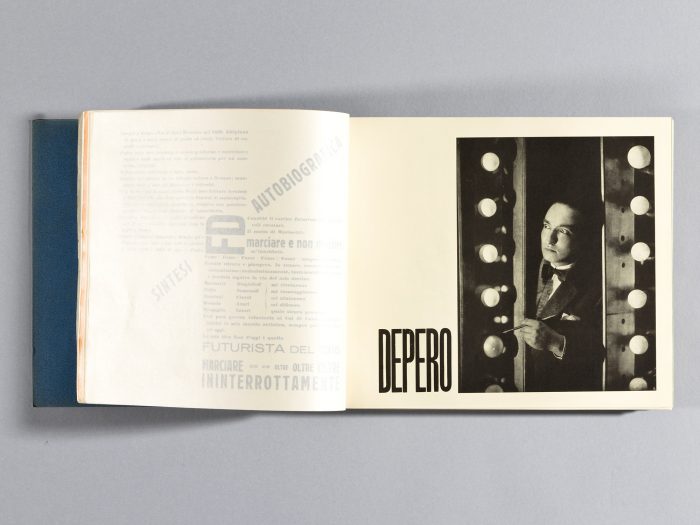

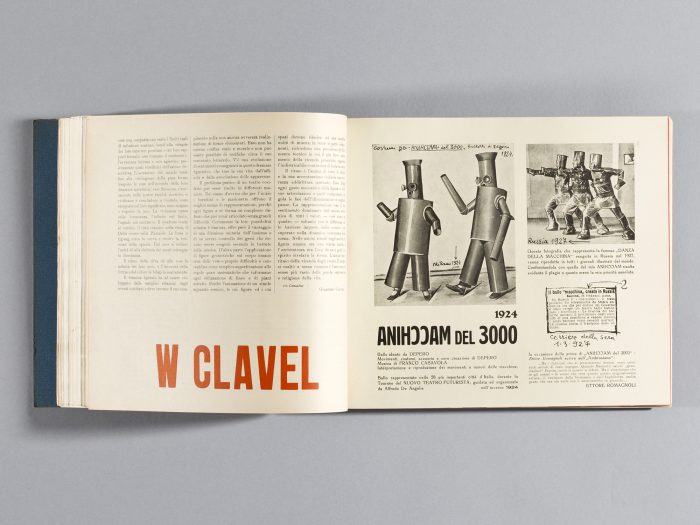

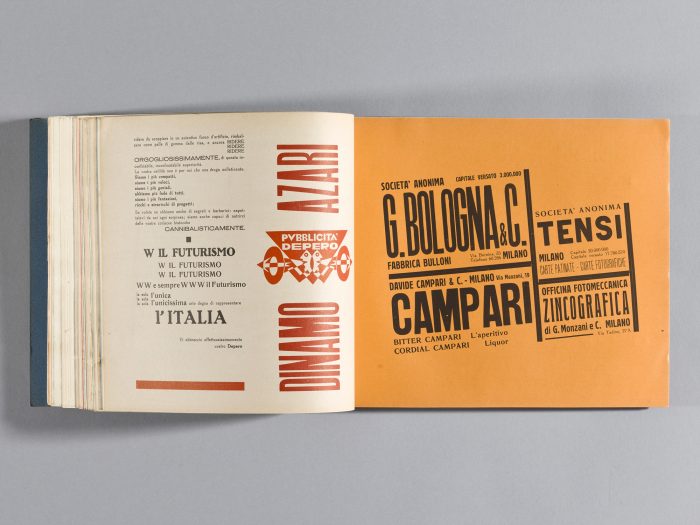

For at least half a decade now, New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum has been digitizing its exhibition catalogs and other art books. Now you can find all of the publications made available so far — not just to read, but to download in PDF and ePub formats — at the Internet Archive. If you’ve visited the Guggenheim’s non-digital location on Fifth Avenue even once, you know how much effort the institution puts toward the preservation and presentation of modern art, and that comes through as much in its printed material as it does in its shows.

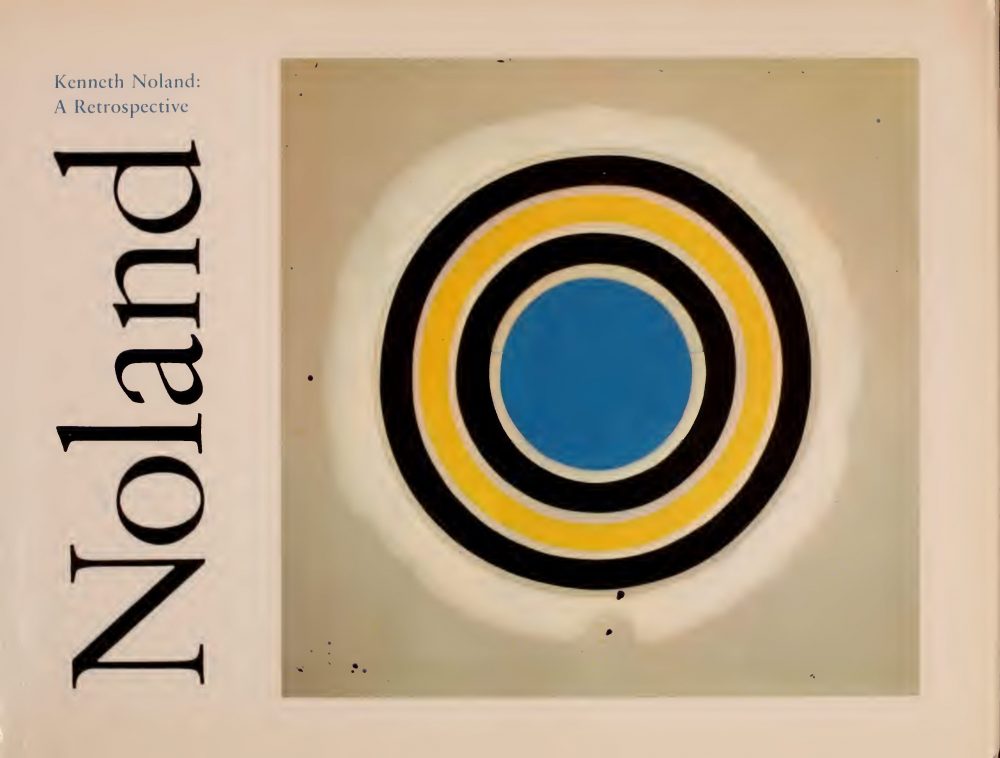

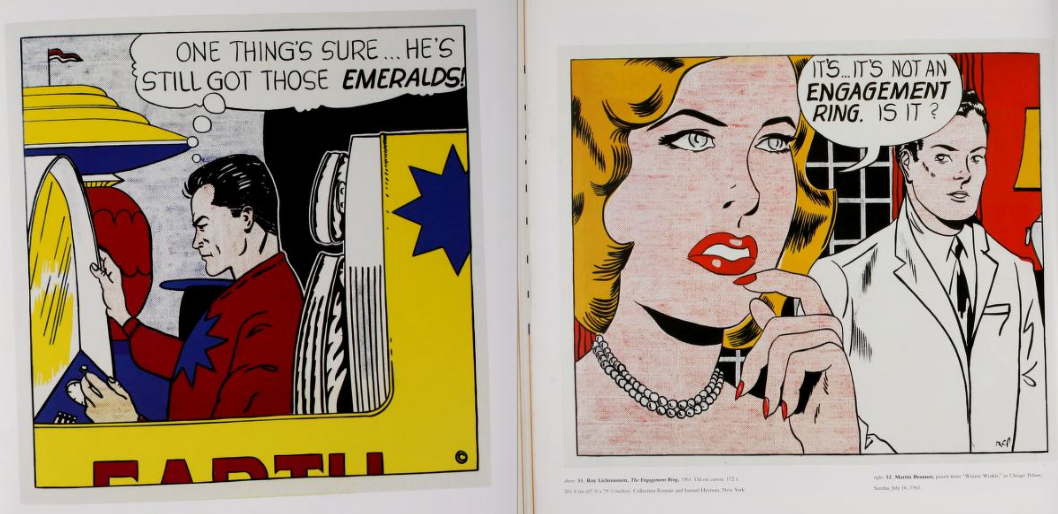

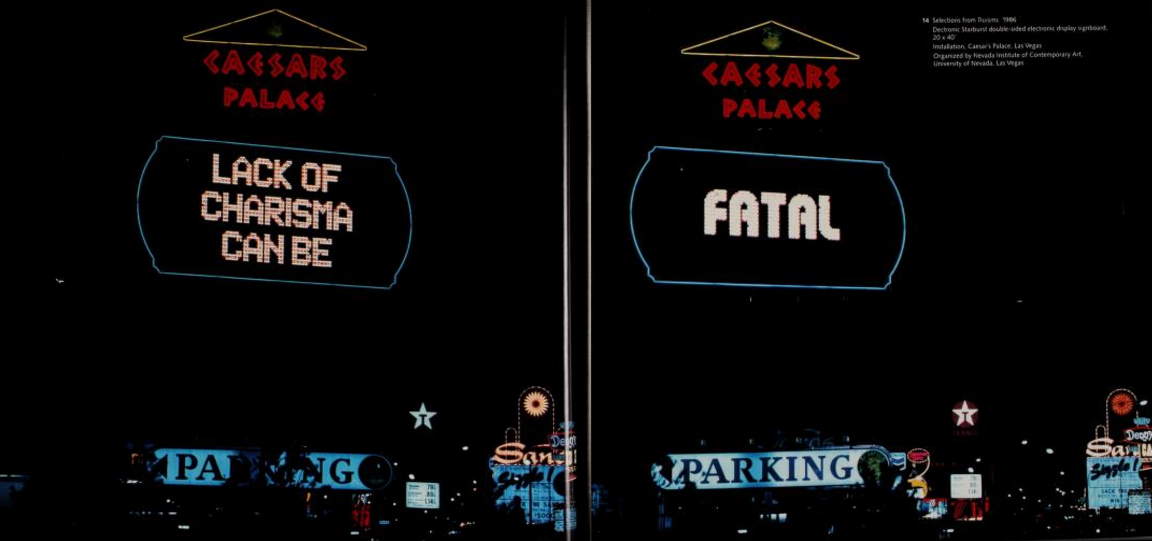

Among the more than 200 Guggenheim art books available on the Internet Archive, you’ll find one on a 1977 retrospective of Color Field painter Kenneth Noland, one on the ever-vivid icon-making pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, and one on the existential slogans — “MONEY CREATES TASTE,” “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT,” “LACK OF CHARISMA CAN BE FATAL” — slyly, digitally inserted into the lives of thousands by Jenny Holzer. Other titles, like Expressionism, a German Intuition 1905–1920, From van Gogh to Picasso, from Kandinsky to Pollock, and painter Wassily Kandinsky’s own Point and Line to Plane, go deeper into art history.

Where to start amid all these books of modern (and even some of pre-modern) art? You might consider first having a look at the books in the Internet Archive’s Guggenheim collection about the Guggenheim itself: the handbook to its collection up through 1980, for instance, or 1991’s Masterpieces from the Guggenheim Collection: From Picasso to Pollock, or the following year’s Guggenheim Museum A to Z, or Art of this Century: The Guggenheim Museum and its Collection from the year after that. But just as when you pay a visit to the Guggenheim itself, you shouldn’t worry too much about what order you see everything in; the important thing is to look with interest.

Explore the collection of 200+ art books and catalogues here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Download 448 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Download Over 300+ Free Art Books From the Getty Museum

The Guggenheim Puts Online 1600 Great Works of Modern Art from 575 Artists

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.