According to DEVO’s co-principle songwriter and bassist Gerald Casale, the experimental art band turned early MTV pop-punk darlings were “pro-information, anti stupid conformity and knew that the struggle for freedom against tyranny is never-ending.”

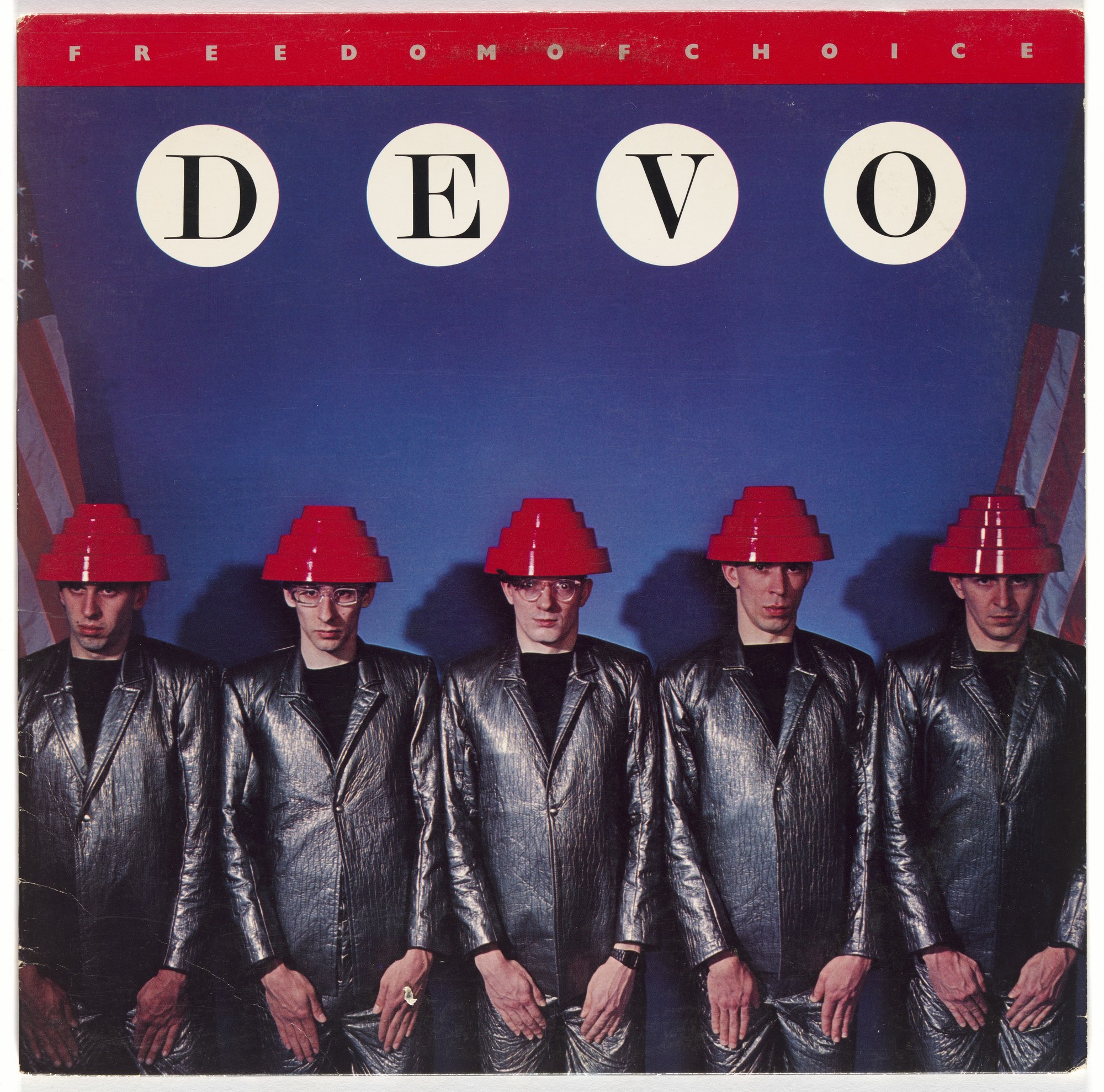

Their singular performance garb also set them apart, and none more so than the bright red plastic Energy Dome helmets they donned 40 years ago this month, upon the release of their third album, Freedom of Choice.

The record, which the band conceived of as a funk album, exploded into mainstream consciousness. The visuals may have made an even more lasting impact than the music, which included the chart topping “Whip It.”

Even the most anti-New Wave metalhead could identify the source of those domes, which have been likened to upturned flower pots, dog bowls, car urinals, and lamp shades.

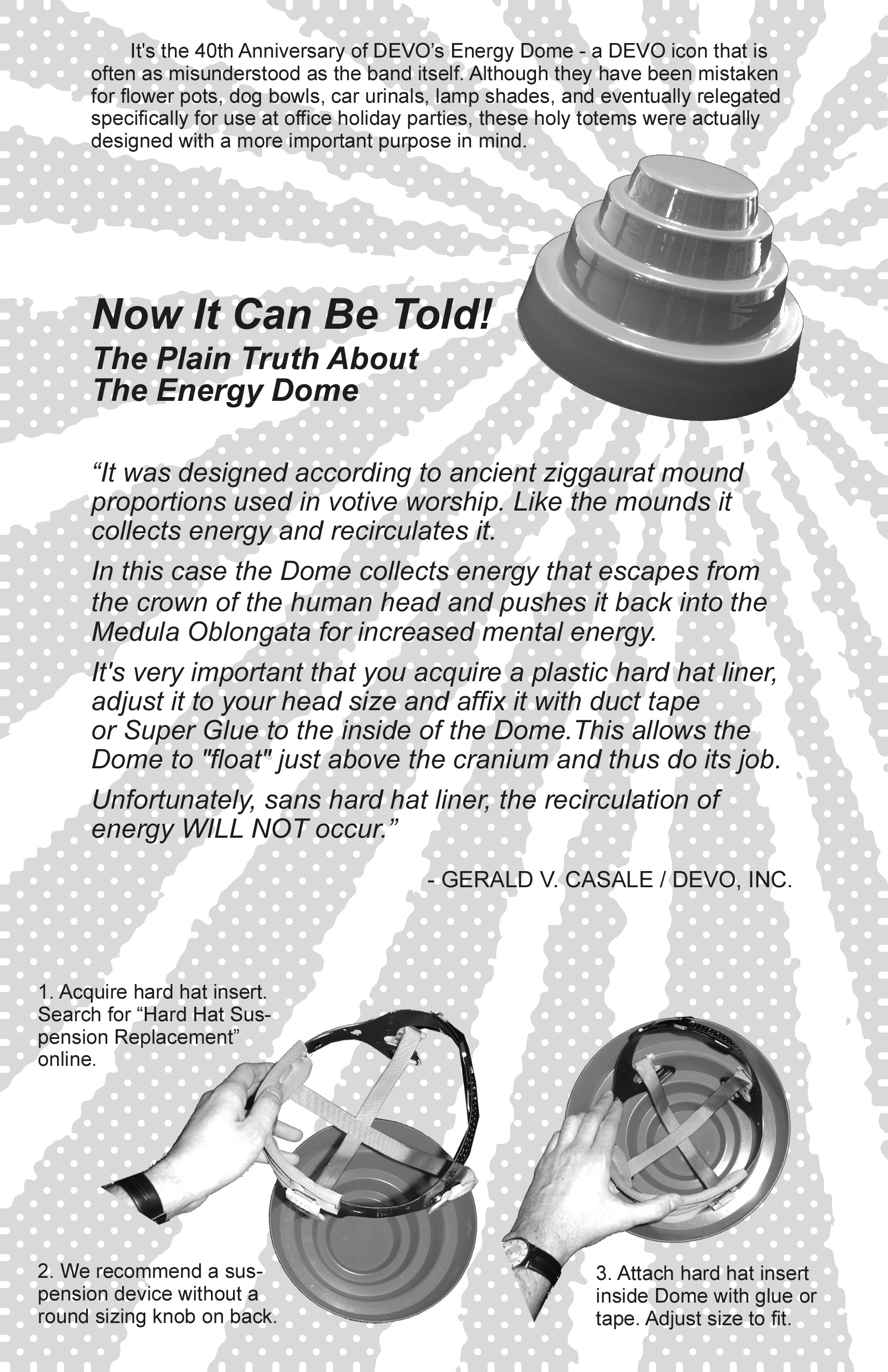

What they probably don’t know is the Energy Dome was “designed according to ancient ziggurat mount proportions used in votive worship. Like the mounds, it collects energy and recirculates it. In this case, the dome collects energy that escapes from the crown of the human head and pushes it back into the Medula Oblongata for increased mental energy.”

Thus sayeth Casale, anyway.

DEVO’s 2020 concert plans were, of course, scotched by the coronavirus pandemic, but the band has found an alternative way to mark the 40th anniversary of Freedom of Choice and the birth of its iconic headgear.

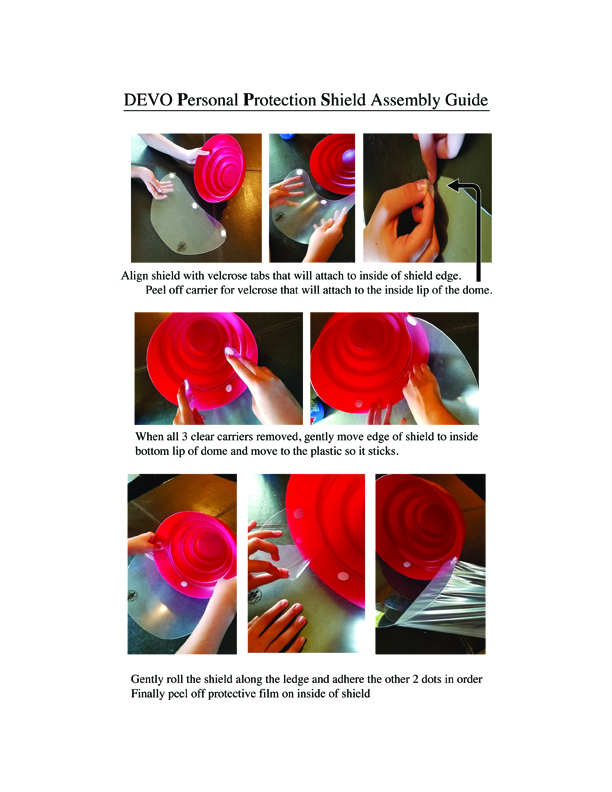

In addition to face masks emblazoned with the familiar red tiered shape, DEVOtees with money and confidence to spare can ante up for a DIY Personal Protective Equipment kit that transforms a standard-issue Energy Dome into a face shield.

It’s worth noting that before taking your converted energy dome out for a particle deflecting spin, you’ll have to truffle up a hard hat suspension liner and install it for a proper fit.

Casale heralded the opening of DEVO’s merch store in a Facebook post:

Here we are 40 years later, living in the alternate reality nightmare spawned by Covid 19 and the botched response of our world “leaders” to do the right thing quickly. We are not exaggerating when we say that 2020 could be the last time you might be able to exercise your freedom of choice. If you don’t use it, you can certainly lose it.

Uh, he’s talking about voting, right, rather than storming the capitol building to demand the premature reopening of inessential businesses or making outsized threats in response to grocery store mask policies?

Perhaps the power of the Energy Dome is such that it could reawaken the pro-information, anti-stupidity sensibilities of some dormant DEVO fans among the unmasked rank and file.

As Casale himself posited in an interview with American Songwriter: “You make it taste good so that they don’t realize there’s medicine in it.”

Pre-order masks and PPE kits from DEVO’s official merch store.

Download instructions for installing a hard hat suspension replacement inside the Energy Dome prior to attaching the shield.

Related Content:

The Mastermind of Devo, Mark Mothersbaugh, Presents His Personal Synthesizer Collection

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Here latest project is an animation and a series of free downloadable posters, encouraging citizens to wear masks in public and wear them properly. Follow her @AyunHalliday.