It was 2012, and Focus Features flew me and about three dozen other journalists to interview Wes Anderson for his latest movie Moonrise Kingdom right on the beach at Cannes. Though the day was hot enough to produce more than a few leathery topless sunbathers, Anderson wore the exact ‘80s-style beige corduroy suit you might expect him to wear. Just like his eccentric, ironic — and given the setting, uncomfortable — sartorial choices, Anderson’s movies are distinctive from frame one. He is Hollywood’s current reigning formalist.

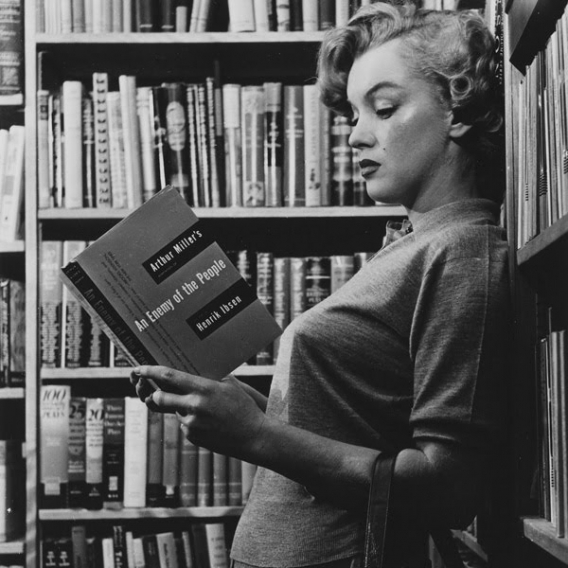

Moonrise Kingdom is probably his most successful recent movie. Though the film is filled with his trademark symmetrical framing, deadpan set design and off-kilter juxtapositions, the film never feels like self-parody, unlike some of his previous movies — think Darjeeling Limited. Set on the remote New Penzance Island in 1965, Moonrise is about a star-crossed pre-teen love affair between Sam, a precocious bespectacled boy scout in a coonskin cap, and Suzy, a troubled teen who favors saddle shoes, raccoon-like eye makeup and above all books. Before she steals away into the woods with Sam, she stuffs her suitcase with six of her favorite (fictitious) books, all swiped from the local library.

Anderson features the books prominently in the movie, giving them titles like The Girl from Jupiter or Disappearance of the 6th Grade. Each book was designed by artists that Anderson personally commissioned. Though Suzy reads parts from three of the books in the film, Anderson originally had a much grander vision: “At one point in the process, when she’s reading these passages from these books,” he told Entertainment Weekly. “I’d thought about going into animation.” The filmmaker had just completed his stopmotion movie The Fantastic Mr. Fox; clearly, animation was on Anderson’s mind.

Ultimately, Anderson decided against this approach, but the idea still apparently intrigued him. So here it is as a promotional piece for Moonrise. In the span of six weeks, blindingly fast for animation, Anderson and his producer Jeremy Dawson managed to animate passages from all six books – written by the filmmaker – in the style of the book covers. The video is hosted by Bob Balaban who played the Moonrise Kingdom’s tuque-sporting narrator.

“I think we all just pitched in and we pulled a lot of favors because it was not like we spent a ton of money doing it,” said Dawson to EW. “People got excited about it because it was a creative thing rather than if they were making a Snickers ad or something.”

You can see the results above.

Related Content:

Watch 7 New Video Essays on Wes Anderson’s Films: Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums & More

Watch Wes Anderson’s Charming New Short Film, Castello Cavalcanti, Starring Jason Schwartzman

Wes Anderson’s First Short Film: The Black-and-White, Jazz-Scored Bottle Rocket (1992)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.