The 1994 documentary above, Einstein’s Brain, is a curious artifact about an even stranger relic, the brain of the great physicist, extracted from his body hours after he died in 1955. The brain was dissected, then embarked on a convoluted misadventure, in several pieces, across the North American continent. Before Einstein’s Brain tells this story, it introduces us to our guide, Japanese scholar Kenji Sugimoto, who immediately emerges as an eccentric figure, wobbling in and out of view, mumbling awed phrases in Japanese. We encounter him in a darkened cathedral, staring up at a backlit stained-glass clerestory, praying, perhaps, though if he’s praying to anyone, it’s probably Albert Einstein. His first words in heavily accented English express a deep reverence for Einstein alone. “I love Albert Einstein,” he says, with religious conviction, gazing at a stained-glass window portrait of the scientist.

Sugimoto’s devotion perfectly illustrates what a Physics World article described as the cultural elevation of Einstein to the status of a “secular saint.” Sugimoto’s zeal, and the rather implausible events that follow this opening, have prompted many people to question the authenticity of his film and to accuse him of perpetrating a hoax. Some of those critics may mistake Sugimoto’s social awkwardness and wide-eyed enthusiasm for credulousness and unprofessionalism, but it is worth noting that he is experienced and credentialed as a professor in mathematics and science history at the Kinki University in Japan and, according to a title card, he “spent thirty years documenting Einstein’s life and person.”

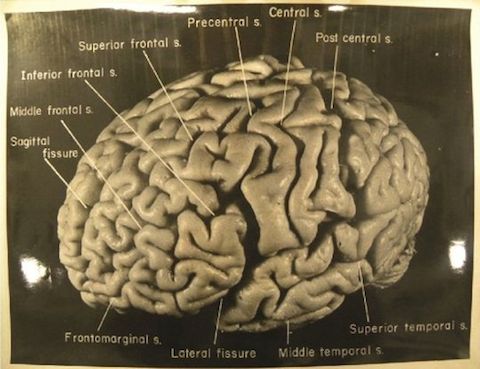

For a full evaluation, see a poorly proofread but very well-sourced article at “bad science blog” Depleted Cranium that tells the complete story of Einstein’s brain, and supports Sugimoto’s tale by reference to several accounts. Of the documentary, we’re told that “based on all available data, the basic premise and the events shown in the documentary are indeed true.” In the film, Sugimoto travels across the U.S. in search of Dr. Thomas Harvey, the man who originally removed Einstein’s brain at Princeton. (See one of the original pathology photos, with added labels, of the brain above). Depleted Cranium continues to set the scene as follows:

Eventually, Sugimoto tracks down Thomas Harvey at his home in Kansas. When he requests to see the brain, Harvey brings out two glass jars containing the pieces. At this point, Sugimoto makes a shocking request: he asks Harvey if he could have a small piece of the brain to keep as a personal memento. Harvey says “I don’t see any reason why not” and proceeds to retrieve a carving knife and a cutting board from his kitchen. He cuts a small section from a sample he identifies as being part of Einstein’s brain stem and cerebellum and gives it to Sugimoto in a small container. In the final scene, Sugimoto celebrates by taking his piece of the brain to a local kereoke [sic] bar and singing a favorite Japanese song.

The notion that the bulk of Einstein’s brain would have ended up in a closet in Kansas seems strange enough. And as for Harvey: the pathologist shopped the brain around for decades—if not for profit, then for notoriety—even driving across the country with journalist Michael Paterniti in 1997 to deliver a large portion of the brain to Dr. Sandra Witelson of McMaster University in Ontario. Paterniti documented the road trip in his book Driving Mr. Albert, which appears to corroborate much of Sugimoto’s narrative, though the trip may itself have been a publicity stunt.

In addition to the brain, Einstein’s eyes were also removed, without authorization, by his ophthalmologist, who kept them in a safety deposit box (where they presumably remain). The entire story of Einstein’s remains is gruesomely outlandish, though one might consider it a modern celebrity example of the centuries-old practice of body snatching. If some or all of this intrigues you, you’ll appreciate Sugimoto’s documentary. Unfortunately, the video upload is rough. It was recorded from Swedish television, has Swedish subtitles, and is generally pretty low-res. However, as a title card at the opening tells us, “due to the extremely limited availability of this documentary, this will have to suffice until a copy of higher quality rises to the surface.”

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Imposes on His First Wife a Cruel List of Marital Demands

The Musical Mind of Albert Einstein: Great Physicist, Amateur Violinist and Devotee of Mozart

Einstein Documentary Offers A Revealing Portrait of the Great 20th Century Scientist

Einstein for the Masses: Yale University Presents a Primer on the Great Physicist’s Thinking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness