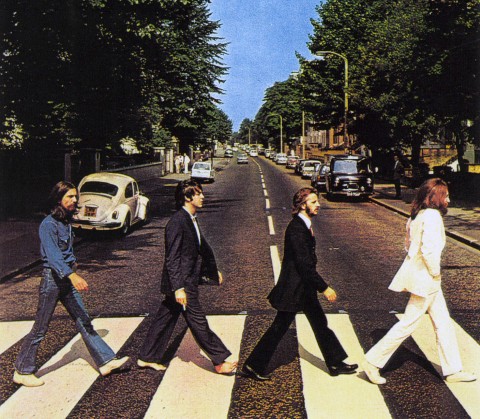

It’s one of the most famous images in pop culture: the four members of the Beatles — John Lennon, Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney and George Harrison — striding single-file over a zebra-stripe crossing on Abbey Road, near EMI Studios in St. John’s Wood, London.

The photograph was taken on the late morning of August 8, 1969 for the cover of the Beatles’ last-recorded album, Abbey Road. The idea was McCartney’s. He made a sketch and handed it to Iain Macmillan, a freelance photographer who was chosen for the shoot by his friends Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Macmillan had only ten minutes to capture the image. A policeman stopped traffic while the photographer set up a ladder in the middle of the road and framed the image in a Hasselblad camera. The Beatles were all dressed in suits by Savile Row tailor Tommy Nutter — except Harrison, who wore denim. It was a hot summer day. Midway through the shoot, McCartney kicked off his sandals and walked barefoot. Macmillan took a total of only six photos as the musicians walked back and forth over the stripes. The fifth shot was the one.

Since then, the crossing on Abbey Road has become a pilgrimage site for music fans from all over the world. Every day, motorists idle their engines for a moment while tourists reenact the Beatles’ crossing. It’s a special place, and filmmaker Chris Purcell captures the sense of meaning it has for people in his thoughtful 2012 documentary, Why Don’t We Do It In the Road? The five-minute film, narrated by poet Roger McGough, won the 2012 “Best Documentary“award at the UK Film Festival and the “Best Super Short” award at the NYC Independent Film Festival. When you’ve finished watching the film, you can take a live look at the crosswalk on the 24-hour Abbey Road Crossing Webcam.

via That Eric Alper

Related Content:

Chaos & Creation at Abbey Road: Paul McCartney Revisits The Beatles’ Fabled Recording Studio

John, Paul and George Perform Dueling Guitar Solos on The Beatles’ Farewell Song (1969)

Bob Egan, Detective Extraordinaire, Finds the Real Locations of Iconic Album Covers