If a Japanese cinephile likes American movies, they probably love David Lynch. I don’t mean to present this as an ironclad rule, but it certainly holds true among my friends. Just as many Americans find something interestingly askew in the fruits of modern Japanese culture, presumably Lynch’s Japanese fans experience his brand of off-kilter Americana — sometimes far off-kilter Americana — just as richly. Observers not particularly familiar with David Lynch have dismissed him as “weird,” just as those not particularly familiar with Japan have dismissed it as “weird.” But those of us familiar with both the filmmaker and the country know that they simply operate on different, and fascinating, sets of sensibilities.

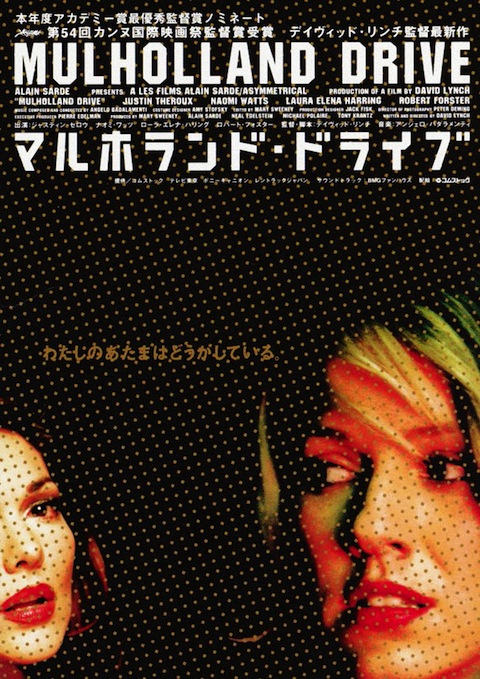

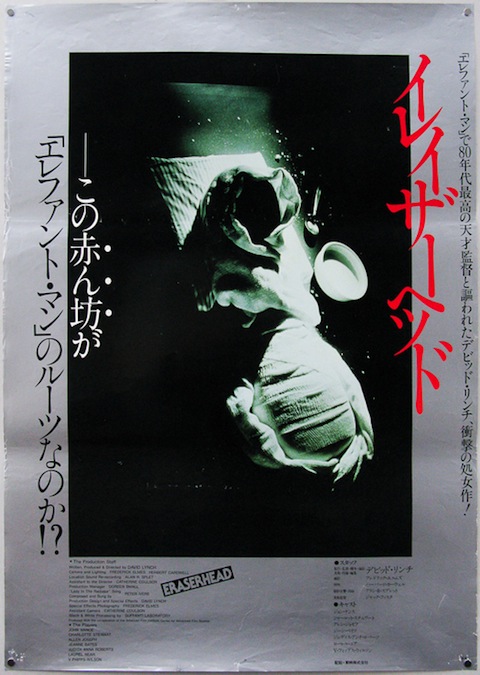

You can see these worlds collide in Biblioklept’s post on Japanese posters advertising David Lynch films. At the top of the post, we have the ominously intriguing one-sheet for Mulholland Drive (or, rendered here in katakana script, “Maruhorando Doraibu”), Lynch’s critically acclaimed 2001 picture that, conceptually, began as a television series to follow up Twin Peaks. “Watashi no atama wa douka shiteiru,” reads the text between the faces of stars Laura Harring and Naomi Watts, which I translate to “Something is the matter with my head” — a viable tagline, come to think of it, for most of Lynch’s works. Just above you’ll find the poster for a personal Lynch favorite, Lost Highway (“Rosuto Haiuei”), clearly also pitched across the Pacific as the director’s mid-nineties comeback. And the chilling nearly abstract image below represents the chilling, abstract movie that started it all, 1977’s Eraserhead — or, Ireizaaheddo:

Related Content:

Eraserhead Stories: David Lynch on the Making of His Famously Nightmarish Movie

David Lynch’s Surreal Commercials

David Lynch in Four Movements: A Video Tribute

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.