Art, as we understand the term, is an activity unique to homo sapiens and perhaps some of our early hominid cousins. This much we know. But the matter of when early humans began making art is less certain. Until recently, it was thought that the earliest prehistoric art dated back some 40,000 years, to cave drawings found in Indonesia and Spain. Not coincidentally, this is also when archaeologists believed early humans mastered symbolic thought. New finds, however, have shifted this date back considerably. “Recent discoveries around southern Africa indicate that by 64,000 years ago at the very least,” Ruth Schuster writes at Haaretz, “people had developed a keen sense of abstraction.”

Then came the “hashtag” in 2018, a drawing in ochre on a tiny flake of stone that archaeologists believe “may be the world’s oldest example of the ubiquitous cross-hatched pattern drawn on a silcrete flake in the Blombos Cave in South Africa,” writes Krystal D’Costa at Scientific American, with the disclaimer that the drawing’s creators “did not attribute the same meaning or significance to [hashtags] that we do.” The tiny artifact, thought to be around 73,000 years old, may have in fact been part of a much larger pattern that bore no resemblance to anything hashtag-like, which is only a convenient, if misleading, way of naming it.

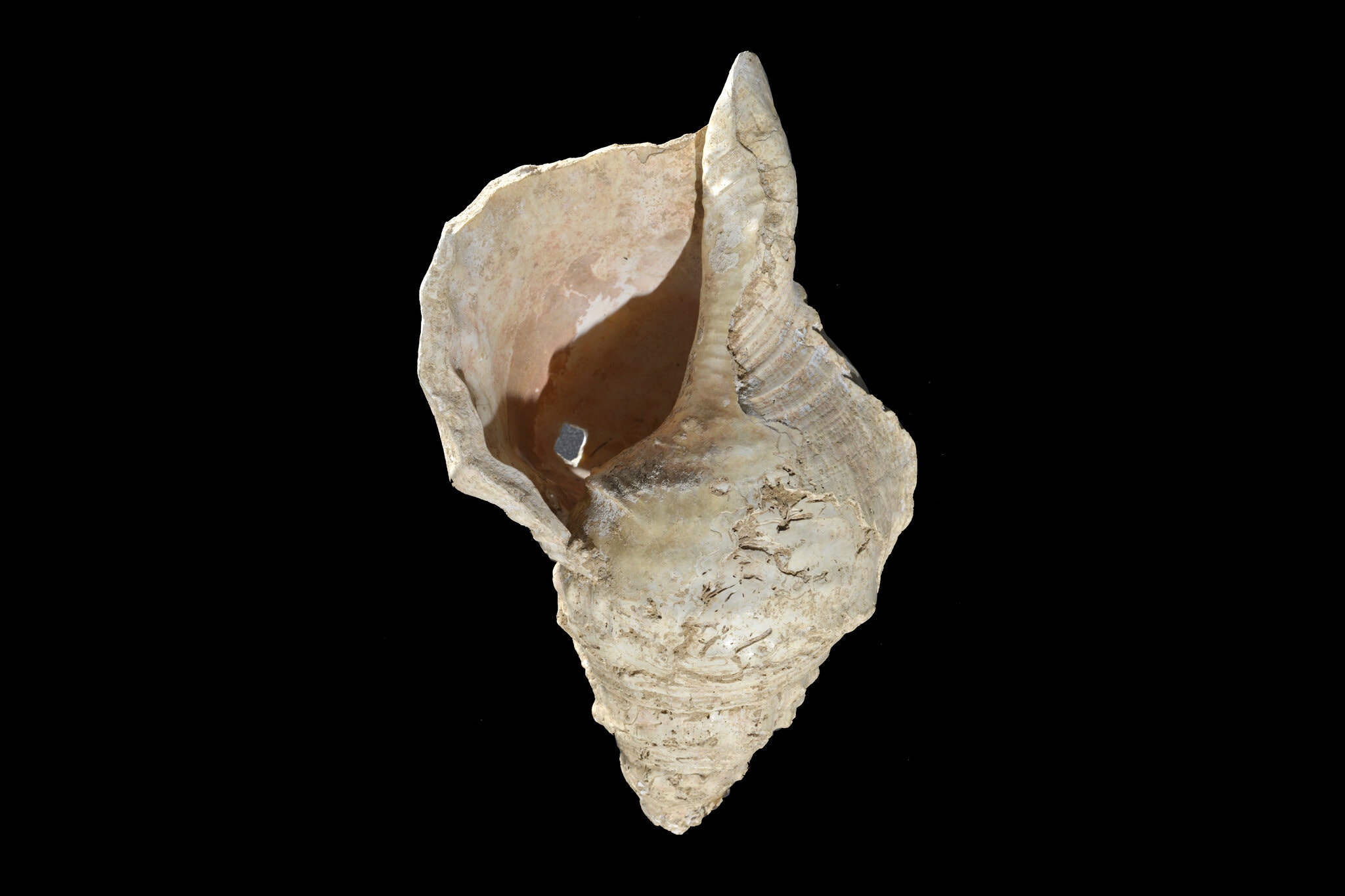

The artifact was recovered from Blombos Cave in South Africa, a site that “has been undergoing excavation since 1991 with deposits that range from the Middle Stone Age (about 100,000 to 72,000 years ago) to the Later Stone Age (about 42,000 years ago to 2,000 years BCE).” These findings have been significant, showing a culture that used heat to shape stones into tools and, just as artists in caves like Lascaux did, used ochre, a naturally occurring pigment, to draw on stone. They made engravings by etching lines directly into pieces of ochre. Archaeologists also found in the Middle Stone Age deposits “a toolkit designed to create a pigmented compound that could be stored in abalone shells,” D’Costa notes.

Nicholas St. Fleur describes the tiny “hashtag” in more detail at The New York Times as “a small flake, measuring only about the size of two thumbnails, that appeared to have been drawn on. The markings consisted of six straight, almost parallel lines that were crossed diagonally by three slightly curved lines.” Its discoverer, Dr. Luca Pollarolo of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, expresses his astonishment at finding it. “I think I saw more than ten thousand artifacts in my life up to now,” he says, “and I never saw red lines on a flake. I could not believe what I had in my hands.”

The evidence points to a very early form of abstract symbolism, researchers believe, and similar patterns have been found elsewhere in the cave in later artifacts. Professor Francesco d’Errico of the French National Center for Scientific Research tells Schuster, “this is what one would expect in traditional society where symbols are reproduced…. This reproduction in different contexts suggests symbolism, something in their minds, not just doodling.”

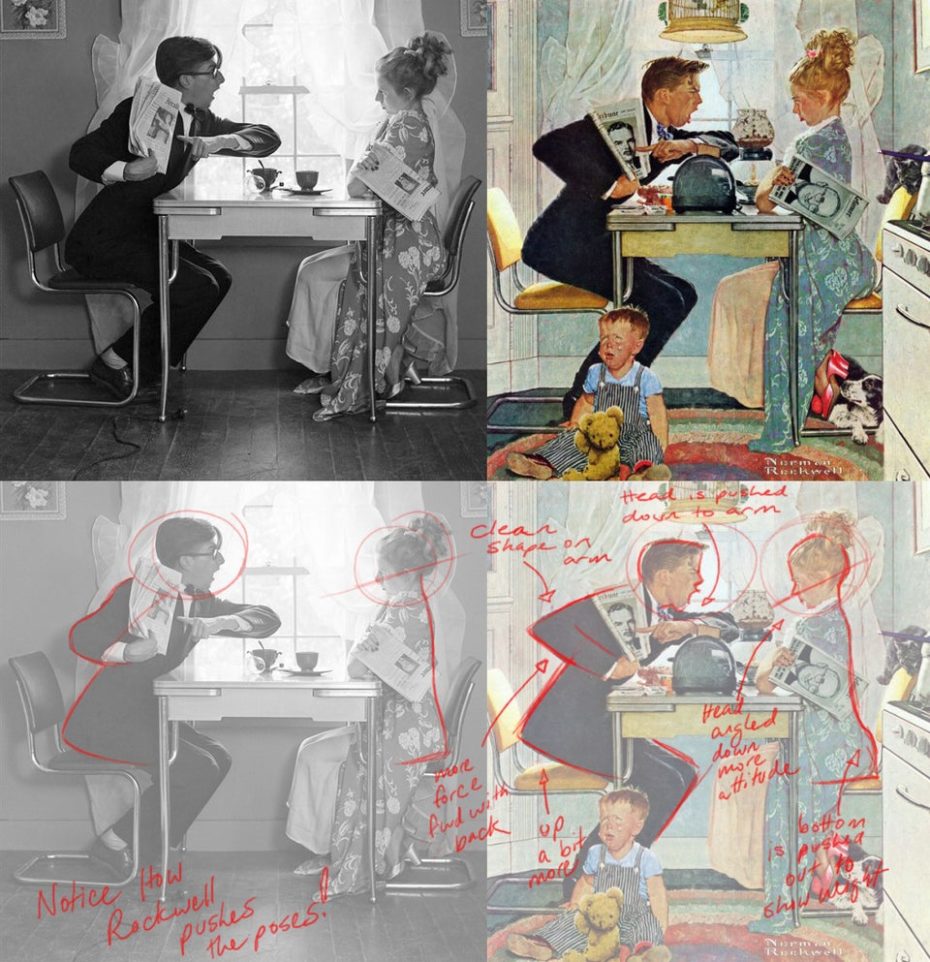

As for whether the drawing is “art”… well, we might as well try and resolve the question of what qualifies as art in our own time. “Look at some of Picasso’s abstracts,” says Christopher Henshilwood, an archaeologist from the University of Bergen and the lead author of a study on the tiny artifact published in Nature in 2018. “Is that art? Who’s going to tell you it’s art or not?”

Researchers at least agree the markings were deliberately made with some kind of implement to form a pattern. But “we don’t know that it’s art at all,” says Henshilwood. “We know that it’s a symbol,” made for some purpose, and that it predates the previous earliest known cave art by some 30,000 years. That in itself shows “behaviorally modern” human activities, such as expressing abstract thought in material form, emerging even closer to the evolutionary appearance of modern humans on the scene.

Related Content:

Hear a Prehistoric Conch Shell Musical Instrument Played for the First Time in 18,000 Years

A Recently-Discovered 44,000-Year-Old Cave Painting Tells the Oldest Known Story

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness