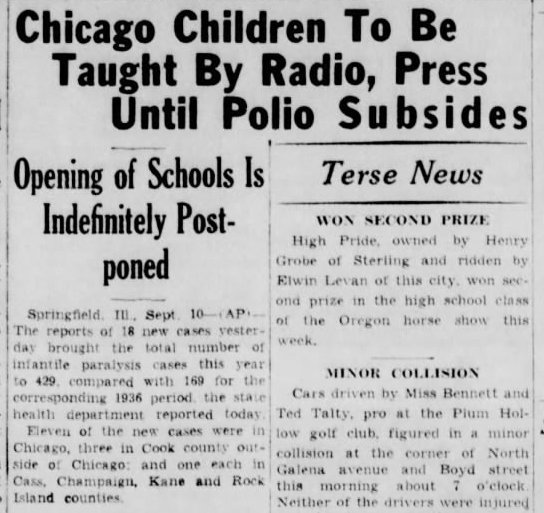

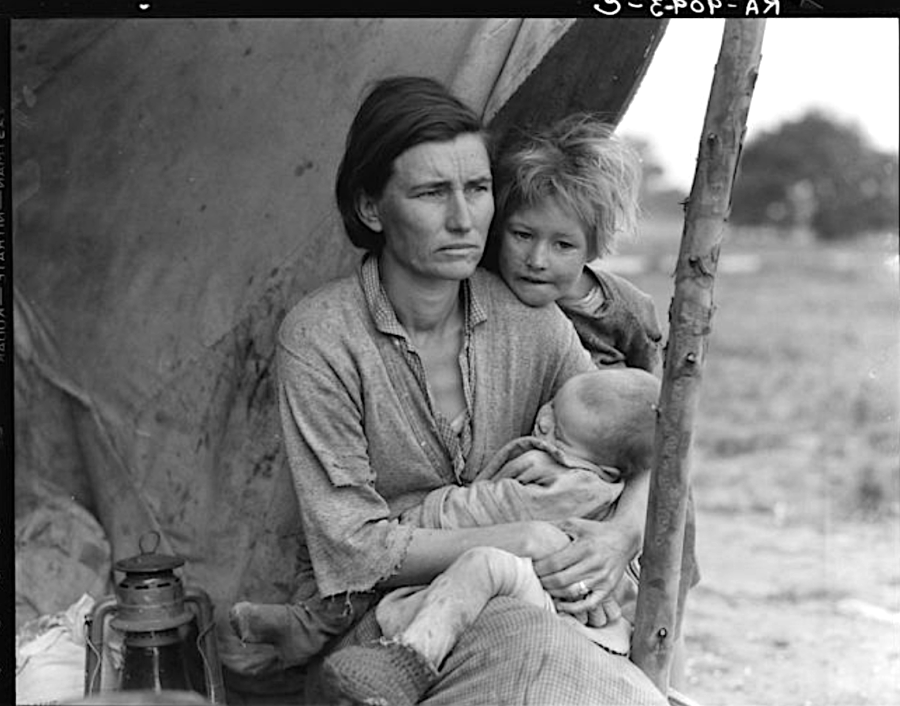

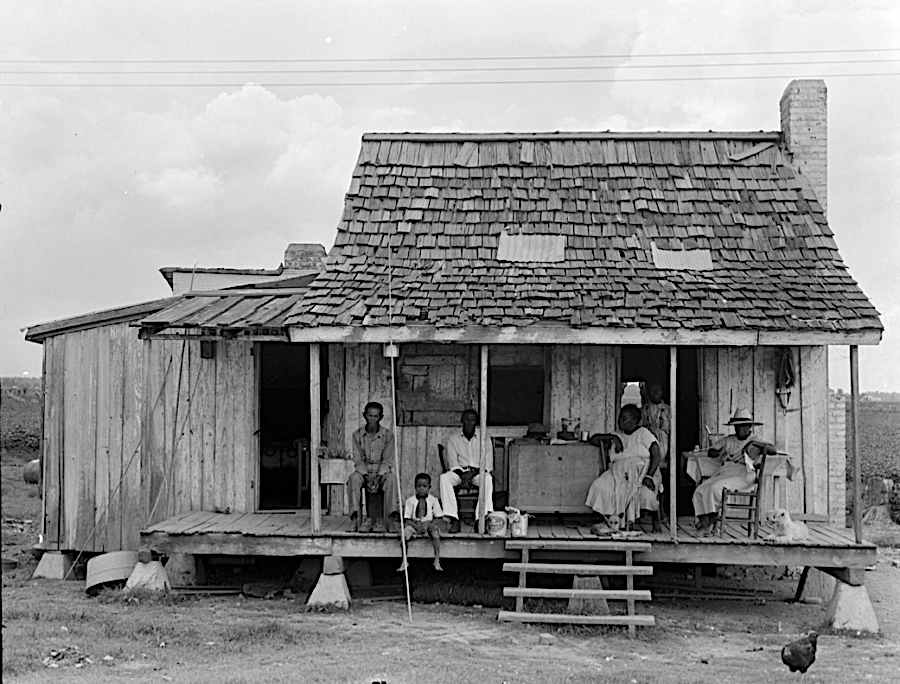

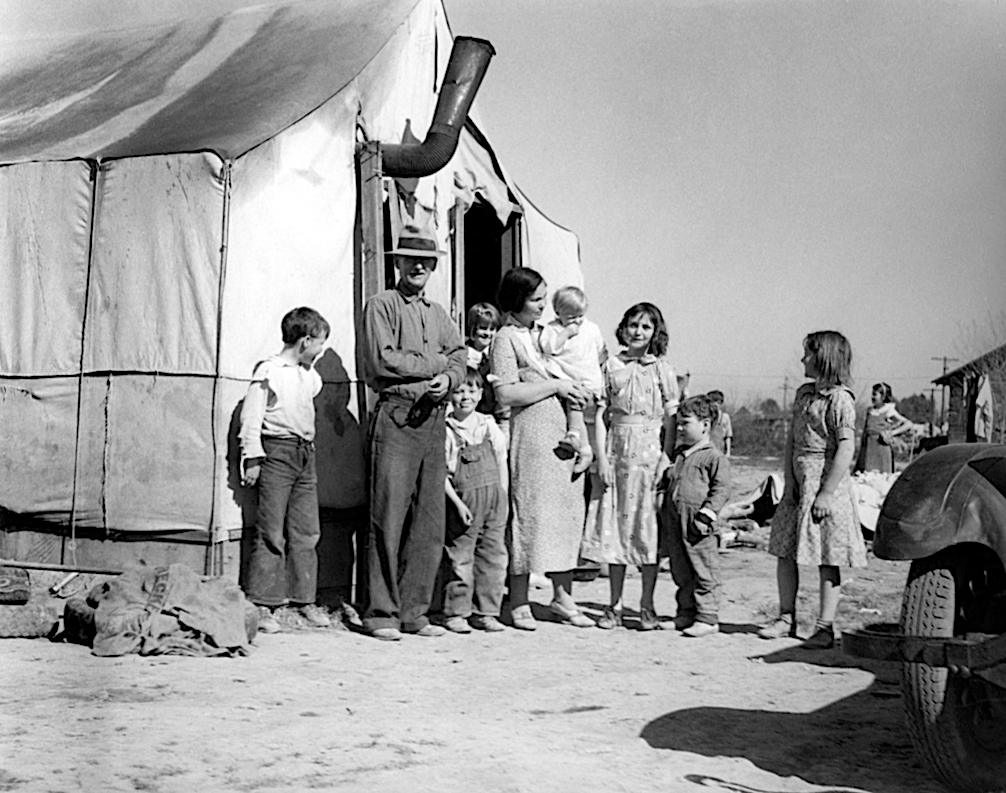

Shortly before her death in 1965, one of the New Deal’s most famous photographers, Dorothea Lange, spoke at UC Berkeley. “Someone showed me photos of migrant farmworkers they had just taken,” she said. “They look just like what I made in the ‘30s.” We can see the same conditions Lange documented almost 60 years later, from the poverty of the Depression to the internment and demonization of immigrants. Only the clothing and the architecture has changed. “Her work could not be more relevant to what’s happening today,” says Lange biographer Linda Gordon.

As an American, it can feel as if the country is stuck in arrested development, unable to imagine a future that isn’t a retread of the past. Yet activists, historians, and therapists seem to agree: in order to move forward, we have to go back—to an honest accounting of how Americans have suffered and suffered unequally from economic hardship and oppression. These were Lange’s great themes: poverty and inequality, and she “believed in the power of photography to make change,” says Erin O’Toole, associate curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Among famous Bay Area colleagues like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, Lange is unique in that “her archive and all that material,” says O’Toole, “stayed in the Bay Area,” held in the possession of the Oakland Museum of California. Now, more than 600 high-resolution scans are available online at the OMCA’s new Dorothea Lange Digital Archive, which also “contains contact sheets, film negatives and links related to materials as additional resources for the many curators, scholars and general audiences accessing Lange’s body of work,” Emily Mendel writes at The Oaklandside.

The digital archive will likely expand in coming years as the digitization process—funded by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation—continues. The physical archive is vast, including some “40,000 negatives and 6,000 prints, plus other memorabilia.” These were inaccessible to anyone who couldn’t make the “huge trek to OMCA,” Lange’s goddaughter Elizabeth Partridge—author of Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning (2013)—remarks. The project is “the most important thing,” says Partridge, “that has happened to her work since it was given to the museum decades ago” by her second husband Paul Taylor.

The online archive-slash-exhibit divides Lange’s work in four sections: “The Depression,” “World War II at Home,” “Post-War Projects,” and “Early Work/Personal Work.” The first of these contains some of her most famous photographs, including versions and adaptations of Migrant Mother, the posed portrait of Florence Thompson that “became a famous symbol of white motherhood” (though Thompson was Native American) and “moved many Americans to support relief efforts.” We can see how the iconic photo was taken up and used by the Cuban journal Bohemia, the Black Panther Party newspaper, and The Nation, who imagined Thompson in 2005 as a Walmart employee.

In the second category are Lange’s photographs of Japanese internment camps, unseen until relatively recently. “When she finally gave these photos to the Army who hired her,” Gordon notes, “they fired her and impounded the photos.” Lange’s skilled portraiture, her uncanny ability to humanize and universalize her subjects, could not suit the purposes of the U.S. military. “She used photography,” O’Toole says, “as a tool to uncover injustices, discrimination, to call attention to poverty, the destruction of the environment, immigration…. The protests that are happening today would be something she’d be photographing in the streets.”

Maybe in a digital age, when we are overwhelmed by visual stimuli, photography has lost much of the influence it once had. But Lange’s images still inspire equal amounts of compassion and curiosity. As Americans contend with the very same issues, we could do with a lot more of both. Enter the Dorothea Lange Digital Archive here.

Related Content:

How Dorothea Lange Shot, Migrant Mother, Perhaps the Most Iconic Photo in American History

478 Dorothea Lange Photographs Poignantly Document the Internment of the Japanese During WWII

Yale Presents an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness