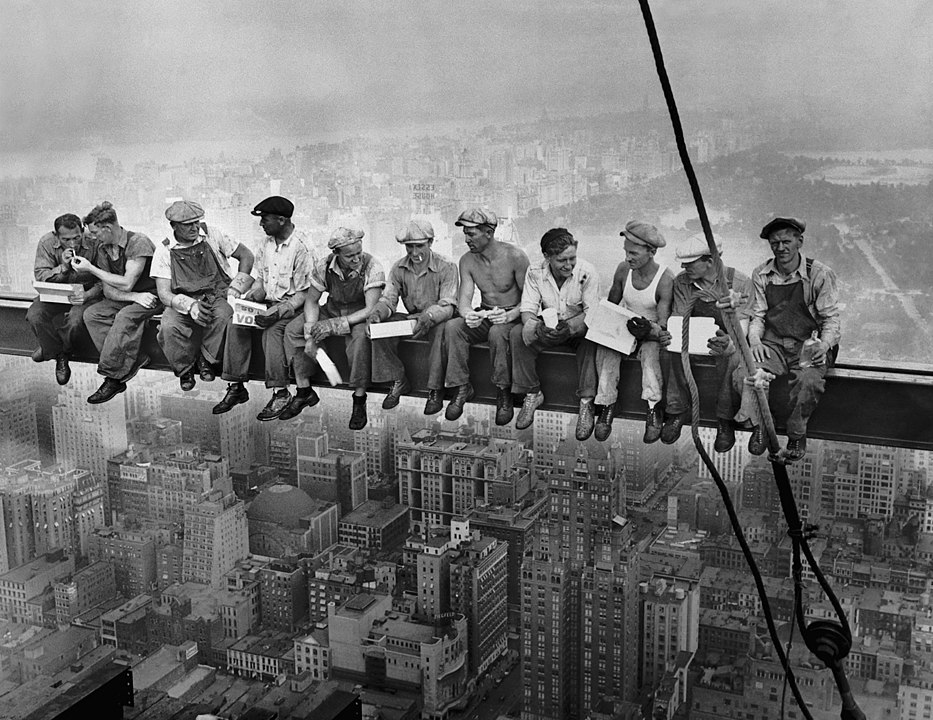

So much classic black and white footage has been digitally colorized recently, it’s hard to remember that the Eastman Kodak Company’s Kodachrome film debuted way back in 1935.

The above footage of New York City was shot by an unknown enthusiast in and around 1937.

Dick Hoefsloot, the Netherlands-based videographer who posted it to YouTube after tweaking it a bit for motion stabilization and speed-correction, is not averse to artificially coloring historic footage using modern software, but in this case, there was no need.

It was shot in color.

If things have a greenish cast, that’s owing to the film on which it was shot. Three-color film, which added blue to the red-green mix, was more expensive and more commonly used later on.

Hoefsloot’s best guess is that this film was shot by a member of a wealthy family. It’s confidently made, but also seems to be a home movie of sorts, given the presence of an older woman who appears a half dozen times on this self-guided tour of New York sites.

There’s plenty here that remains familiar: the Woolworth Building and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, trussed up Christmas trees propped against makeshift sidewalk stands, the New York Public Library’s lions, Patience and Fortitude.

Other aspects are more a matter of nostalgia.

Over in Times Square, Bulldog Drummond Comes Back starring John Barrymore was playing at the Criterion (now the site of a Gap store), while the Paramount Theater, now a Hard Rock Cafe, played host to True Confession with Barrymore and Carol Lombard.

Oysters were still food for the masses, though records show that locally harvested ones had been deemed too polluted for human consumption for at least a decade.

A bag of peanuts cost 15¢. A new Oldsmobile went for about $914 plus city tax.

Laundry could be seen strung between buildings (still can be on occasion), but people dressed up carefully for shopping trips and other excursions around town. Heaven forbid they step outside without a hat.

Though the Statue of Liberty makes an appearance, the film doesn’t depict the neighborhoods where new and established immigrants were known to congregate. Had the camera traveled uptown to the Apollo—by 1937, the largest employer of black theatrical workers in the country and the sole venue in the city in which they were hired for backstage positions—the overall composition would have proved less white.

The film, which was uploaded a little over a year ago, has recently attracted a fresh volley of attention, leading Hoefsloot to reissue his request for viewers to “refrain from (posting) political, religious or racist-related comments.”

In this fraught election year, we hope you will pardon a New Yorker for pointing out the legion of commenters flouting this polite request, so eager are they to fan the fires of intolerance by expressing a preference for the “way things used to be.”

With all due respect, there aren’t many people left who were present at the time, who can accurately recall and describe New York City in 1937. Our hunch is that those who can are not spending such time as remains rabble-rousing on YouTube.

So enjoy this historic window on the past, then take a deep breath and confront the present that’s revealing itself in the YouTube comments.

A chronological list of New York City sites and citizens appearing in this film circa 1937:

00:00 Lower Manhattan skyline seen from Brooklyn Heights Promenade

00:45 Staten Island steam ferry

01:05 RMS Carinthia

01:10 Old three-stack pass.ship, maybe USS Leviathan

01:28 One-stack pass.ship, name?

01:50 HAL SS Volendam or SS Veendam II

02:18 Westfield II steam ferry to Staten Island, built 1862?

02:30 Floyd Bennett Airfield, North Beach Air Service inc. hangar

02:43 Hoey Air Services hangar at F.B. Airfield

02:55 Ladies board monoplane, Stinson S Junior, NC10883, built 1931

03:15 Flying over New York: Central Park & Rockefeller Center

03:19 Empire State Building (ESB)

03:22 Chrysler building in the distance

03:26 Statue of Liberty island

03:30 Aircraft, Waco ZQC‑6, built 1936

03:47 Reg.no. NC16234 becomes readable

04:00 Arrival of the “Fly Eddie Lyons” aircraft

04:18 Dutch made Fokker 1, packed

04:23 Douglas DC3 “Dakota”, also packed, new

04:28 Green mono- or tri-engine aircraft, type?

04:40 DC3 again. DC3’s flew first on 17 Dec.1935

04:44 Back side of Woolworth Building

05:42 Broadway at Bowling Green

05:12 Brooklyn across East River, view from Pier 11

05:13 Water plane, Grumman G‑21A Goose

05:38 Street with bus, Standard Oil Building ®

05:40 Truck, model?

05:42 Broadway at Bowling Green

05:46 Old truck, “Engels”, model?

05:48 Flag USA with 48 stars!

05:50 Broadway at Bowling Green, DeStoto Sunshine cab 1936

05:52 Truck, “Bier Mard Bros”, model?

05:56 Ford Model AA truck 1930

05:58 Open truck, model?

06:05 Standard Oil Building

06:25 Bus 366 & Ford Model A 1930

06:33 South Street & Coenties Slip

06:35 See 07:19, Black car?

06:45 Cities Service Building at 70 Pine St. right. Left: see 07:12

06:48 Small vessels in the East River

06:50 Owned by Harry F. Reardon

07:05 Shack on Coenties Slip, Pier 5

07:12 City Bank-Farmers Trust Building, 20 Exchange Place

07:15 Oyster bar, near Coenties Slip

07:19 South Street, looking North towards the old Seaman’s Church Institute

07:31 Holland America Line, Volendam‑I, built 1922

07:32 Chrysler Plymouth P2 De Luxe

07:34 Oyster vendor

08:05 Vendor shows oyster in pot

08:16 Wall st.; Many cars, models?

08:30 Looking down Wall st.

08:52 More cars, models?

09:00 Near the Erie Ferry, 1934/35 Ford s.48 De Luxe

09:02 Rows of Christmas tree sales, location?

09:15 Erie Railroad building, location? Quay 21? Taxi, model?

09:23 1934 Dodge DS

09:25 See 09:48

09:27 Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad

09:29 Clyde Mallory Lines

09:48 South end of West Side Highway

09:49, 10:08, 10:11, 10:45 Location?

10:25 Henry Hudson Parkway

11:30 George Washington Bridge without the Lower Level

12:07 Presbyterian Hospital, Washington Heights

12:15 Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research

12:49 New York Hospital at 68th St. & East River

13:14 ditto

13:35 ditto

13:42 Metropolitan Museum of Art

14:51 Rockefella Plaza & RCA building

16:33 Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

16:50 Public Library

17:24 Panoramic view, from ESB

17:45 RCA Building, 30 Rockefeller Plaza

18:16 Original Penn Station

19:27 Movie True Confession, rel. 24 Dec.1937

19:30 Sloppy Joes

20:12 Neon lights & Xmas

26:34 Herald Square

29:48 Police Emergency Service (B&W)

31:00 SS Normandie, French Line, Pier 88

32:06 RMS Queen Mary, White Star Line, Pier 92

32:43 Departure Queen Mary

33:45 Italian Line, Pier 84, Terminal, dd.1935

34:00 SS Conte Di Savoia, Italian Line, Pier 84

34:25 Peanut seller, near the piers

34:35 Feeding the pidgeons

34:52 SS Normandie, exterior & on deck

35:30 View from Pier 88

35:59 Interior

37:06 From Pier 88

37:23 Northern, Eastern, Southern or Western Prince, built 1929

37:32 Tug, William C. Gaynor

38:20 Departure

38:38 Blue Riband!

39:15 Tugs push Normandie into fairway

39:50 Under own steam.

40:00 Statue of Liberty

40:15 SS Normandie leaves NYC

View more of Dick Hoefsloot’s historic uploads on his YouTube channel.

Related Content:

A Trip Through New York City in 1911: Vintage Video of NYC Gets Colorized & Revived with Artificial Intelligence

A New Interactive Map Shows All Four Million Buildings That Existed in New York City from 1939 to 1941

The Lost Neighborhood Buried Under New York City’s Central Park

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.