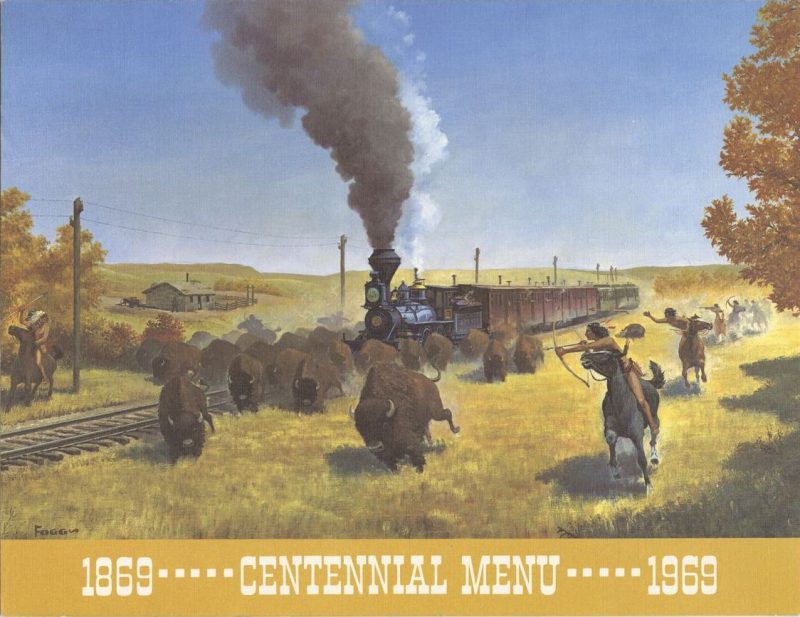

The coming of the railroad in the U.S. of the 19th century meant unprecedented opportunity for millions—a triumph of transportation and commerce that changed the country forever. For many more—including millions of American bison—it meant catastrophe and near extinction. This complicated history has provided a rich field of study for scholars of the period—who can tie the railroad to nearly every major historical development, from the Civil War to presidential campaigns to the spread of the Sears merchandising empire from coast to coast.

But as time wore on, passenger trains became both more commonplace and more luxurious, as they competed with air and auto travel in the early 20th century. It is this period of railroad history that most attracted Ira Silverman as a graduate student at Northwestern University in the 1960s. While enrolled at Northwestern’s Transportation Center in Evanston, Illinois, Silverman and his classmates found endless “opportunities for research, adventure, and unparalleled feasting,” writes Claire Voon at Atlas Obscura.

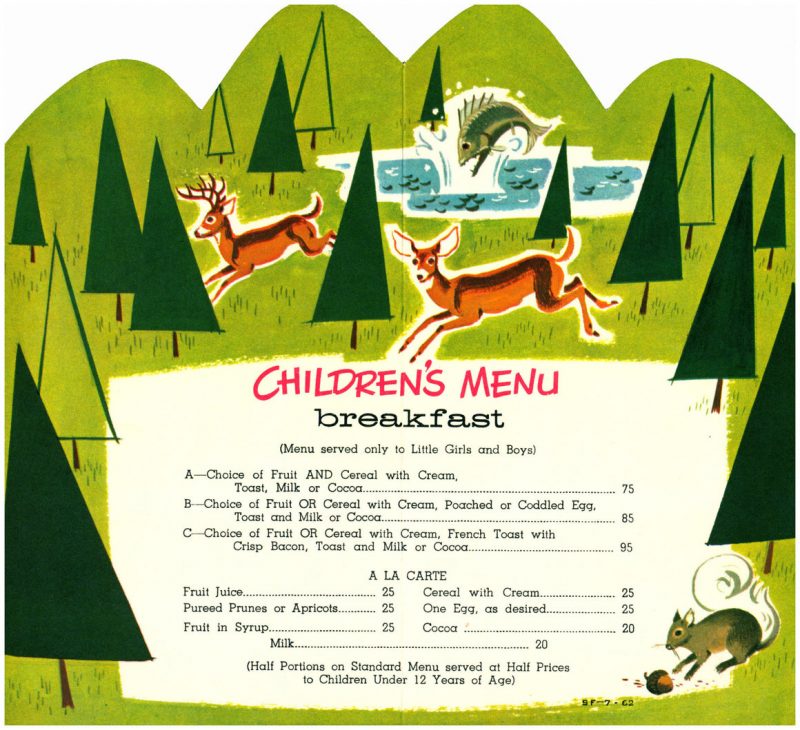

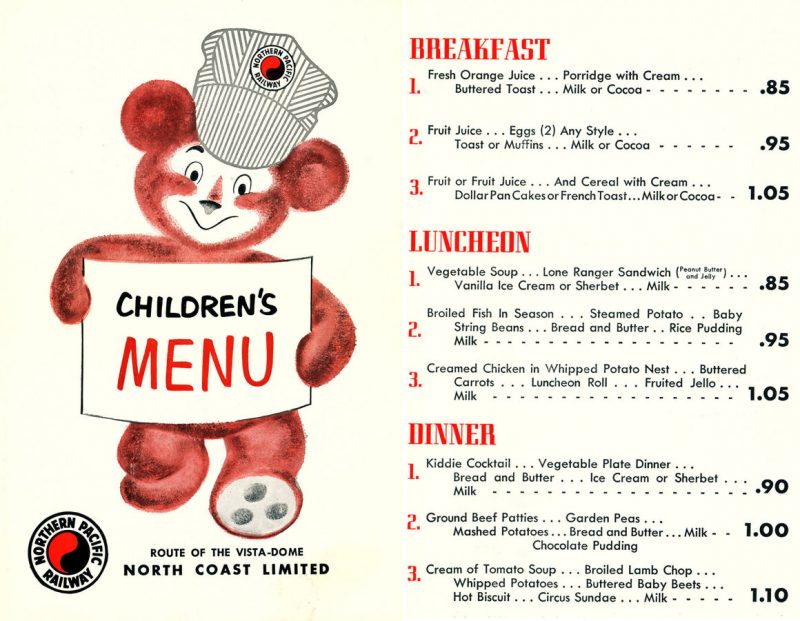

Silverman especially took to the dining cars—and more to the point, to the menus, which he collected by the dozens, “eventually amassing an archive of 238 menus and related pamphlets. After a long career in transit, he donated the collection to his alma mater’s Transportation Library, which recently digitized it in its entirety.” Silverman’s collection represents “35 United States and Canadian railroads,” points out Northwestern, and its contents mostly date from the early 60s to the 1980s—from his most active years riding the rails in style, that is.

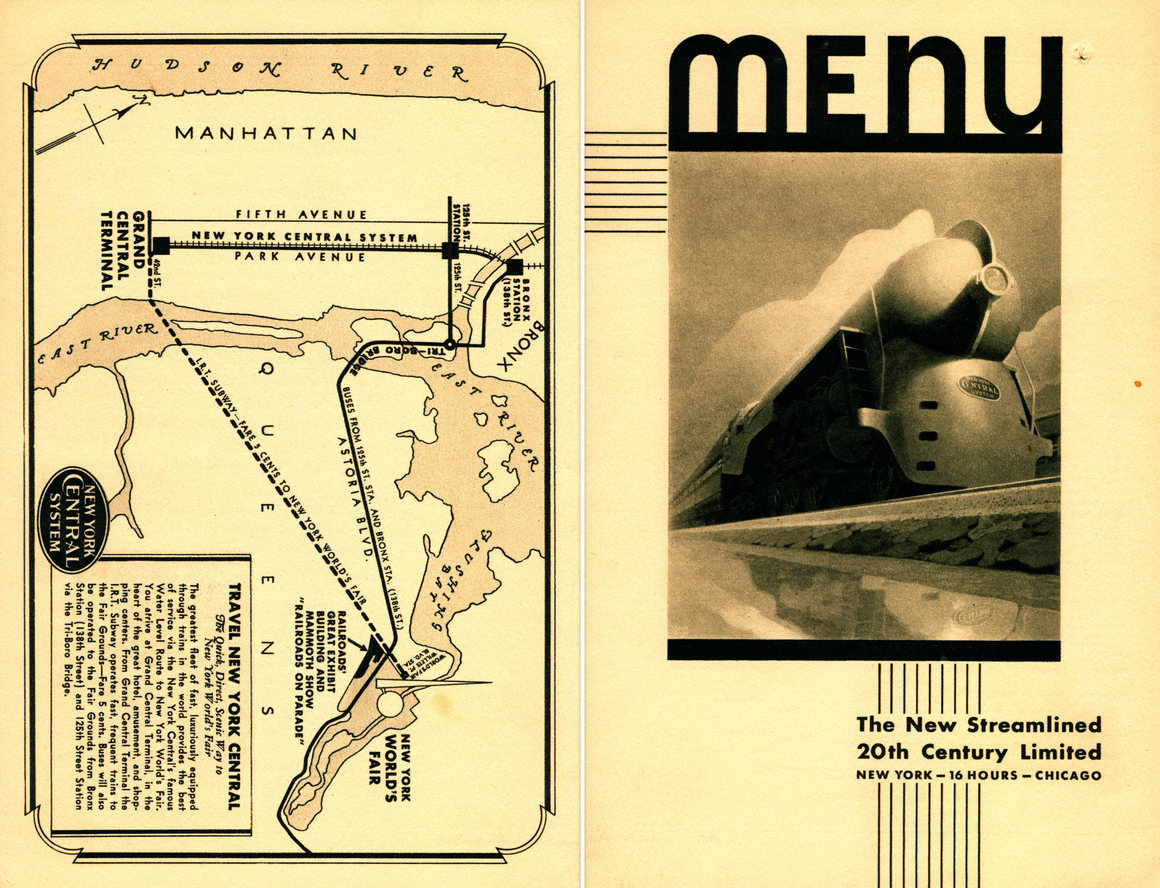

But Silverman was also able to acquire earlier examples, such as a 1939 menu “once perused by passengers aboard the famed 20th Century Limited train,” Voon writes, “which traveled between New York City and Chicago.” Twenty years after this menu’s appearance, Cary Grant, “playing an adman in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, orders a brook trout with his Gibson” while riding the same line. The Art Deco menu for the “new streamlined” line features such delicacies as “genuine Russian caviar on toast and grilled French sardines.”

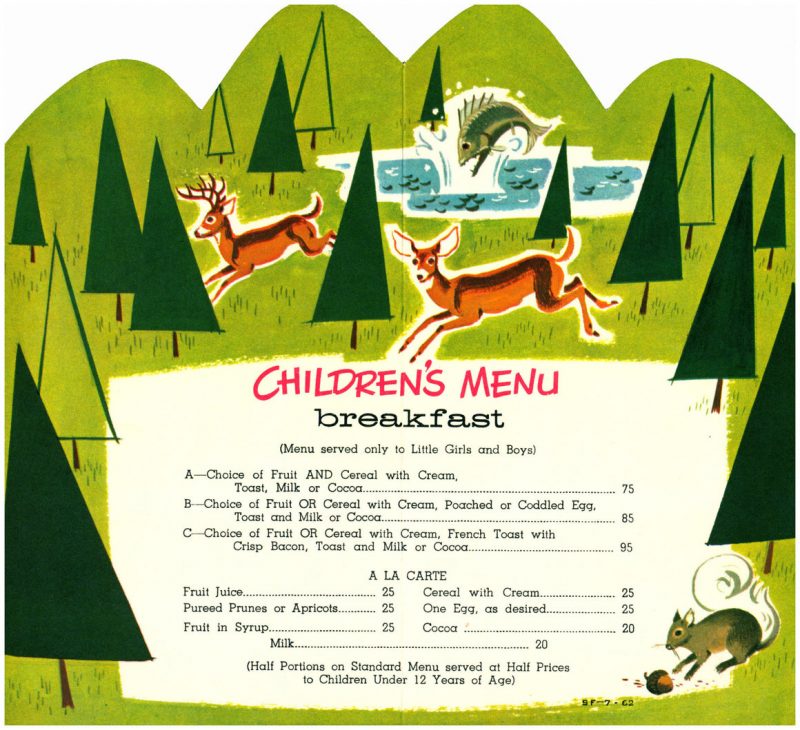

Even kids’ menus—now reliably dominated by chicken fingers, pizza, PB&Js, and mac & cheese—offered far more sophisticated dining than we might expect to find, with “items such as grilled lamb chops, roast beef, and seasonal fish” on the North Coast Limited menu below. “The mid-20th century seems to have been a golden age of railroad dining,” remarks Northwestern Transportation Librarian Rachel Cole. “It was never something that railroads profited on, but they used it to compete against each other and attract passengers,” taking pride in “selections that would be rivaled in restaurants.”

The fine dining-car experience might also include novelty items passengers would be unlikely to find anywhere else, such as Northwestern Pacific’s Great Baked Potato, “a monstrous spud,” Voon explains, “that could weigh anywhere between two to five pounds” and came served with “an appropriately sized butter pat.” One can see the appeal for a food and travel enthusiast like Silverman, who had the privilege of trying dishes on most of these menus for himself.

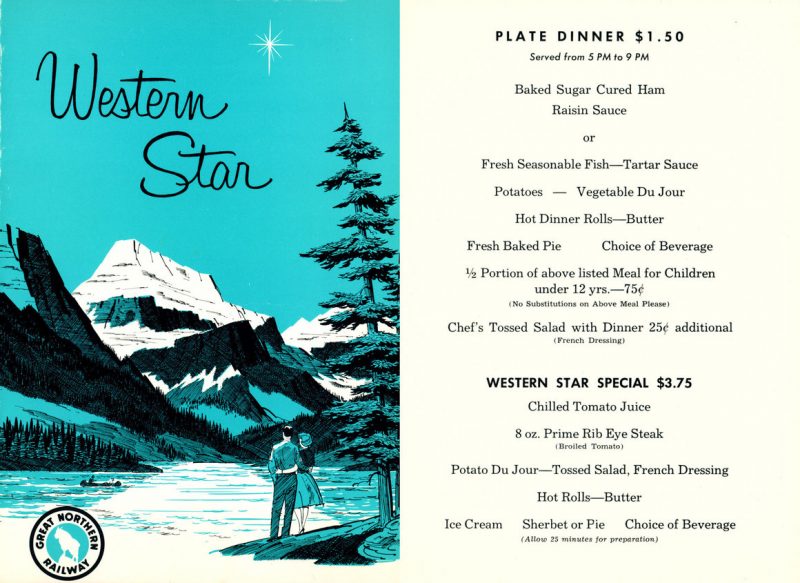

The rest of us will have to rely on our gustatory imaginations to conjure what it might have been like to eat prime rib on the Western Star in the Pacific Northwest in the early 60s, or braised smoked pork loin on an Amtrak train in 1972. If your memories of dining on a train mostly consist of pulling soggy, microwaved “food” from steaming hot plastic bags, or munching on packaged, processed salty snacks, expand your sense of what railroad dining could be at the Ira Silverman Railroad Menu Collection here.

Related Content:

Foodie Alert: New York Public Library Presents an Archive of 17,000 Restaurant Menus (1851–2008)

Mark Twain Makes a List of 60 American Comfort Foods He Missed While Traveling Abroad (1880)

What Prisoners Ate at Alcatraz in 1946: A Vintage Prison Menu

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness