No student of Chinese has an easy time with pronunciation. Even linguist Joshua Rudder, who tells animated stories on his Youtube channel NativeLang about languages around the world and how they came to be, admits his own struggles to get it right. “But lately I’ve been burying myself in hundreds of pages of Chinese linguistic history, and you know what? I’m in good company,” says Rudder in the introduction to the video above, “What ‘Ancient’ Chinese Sounded Like — and How We Know.” “Chinese pronunciation puzzled experts in China for a long, long time.”

This leads into the story of one particular expert, a 19th scholar named Chen Li who sought to recover Chinese pronunciations that even then seemed to have been lost to history. “How do you recover the sounds immortalized in classical texts? How do you make the old poems rhyme again?” And how do you do it when “you have no recordings, no phonetic transcriptions, not even an alphabet — you’re working with characters.” Ah yes, characters, those thousands of logograms, evolved over millennia, that still today bedevil anyone trying to get a handle on the Chinese language, not excluding the Chinese themselves. That goes especially for someone as linguistically ambitious as Chen Li.

Chen Li’s research on the correct pronunciation of ancient Chinese brought him to the Qieyun, an even then-1200-year-old dictionary of fanqie (反切), or the pronunciation of single characters described by using combinations of other characters. (On Wikipedia, you can find assembled links to scanned fragments of the text currently held in places like the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.) Drawing on not just the Qieyun but other sources as well, Chen Li’s painstaking work of reconstructing old pronunciations overturned the long-standing teaching that the Chinese language had 36 initial consonant sounds. He found that it had 41. But even after that discovery, the nature of these “precise sounds” remained unknown, an incompleteness of knowledge chipped away at by the Swedish scholar Bernard Karlgren in the 1900s, who took into account “the many living varieties” of the Chinese language.

Other Asian languages with vocabulary descended from Chinese also come in to play. Rudder takes the example of the word for “country,” pronounced guó (國) in modern Mandarin but kuk in Korean (국), koku in Japanese (国), and kuək in Vietnamese (quốc), all suggesting a common ancient Chinese ancestor word ending in a K‑like consonant sound. But however much progress has been made, this research into “ancient” Chinese has turned out to be research into a linguistic period of “middle Chinese,” which reveals evidence of “an even older language to uncover, a thousand years older still.” The work of a linguistic history, just like the humbler work of a Chinese language-learner, is never done.

Related Content:

What Ancient Latin Sounded Like, And How We Know It

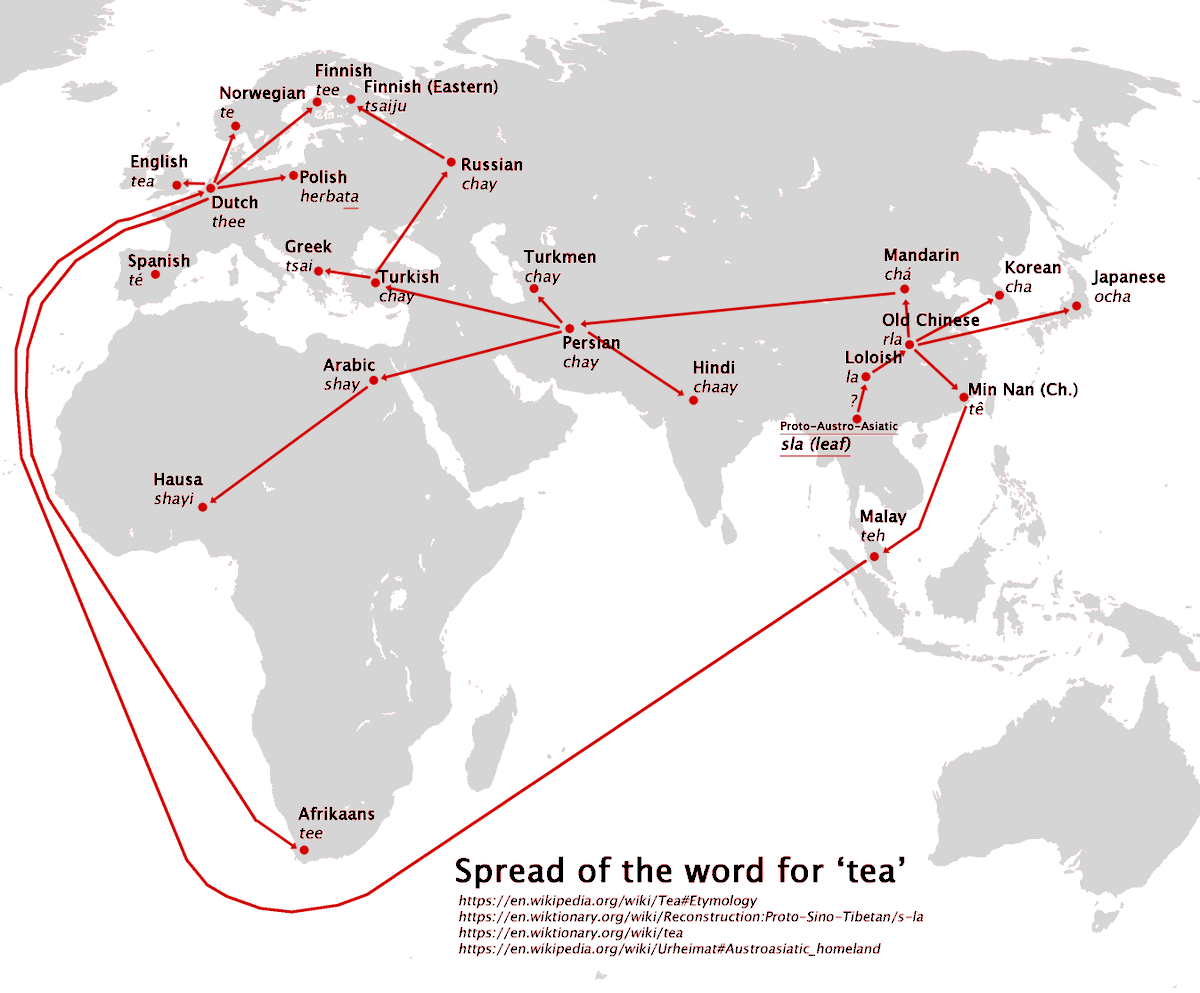

A Map of How the Word “Tea” Spread Across the World

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.