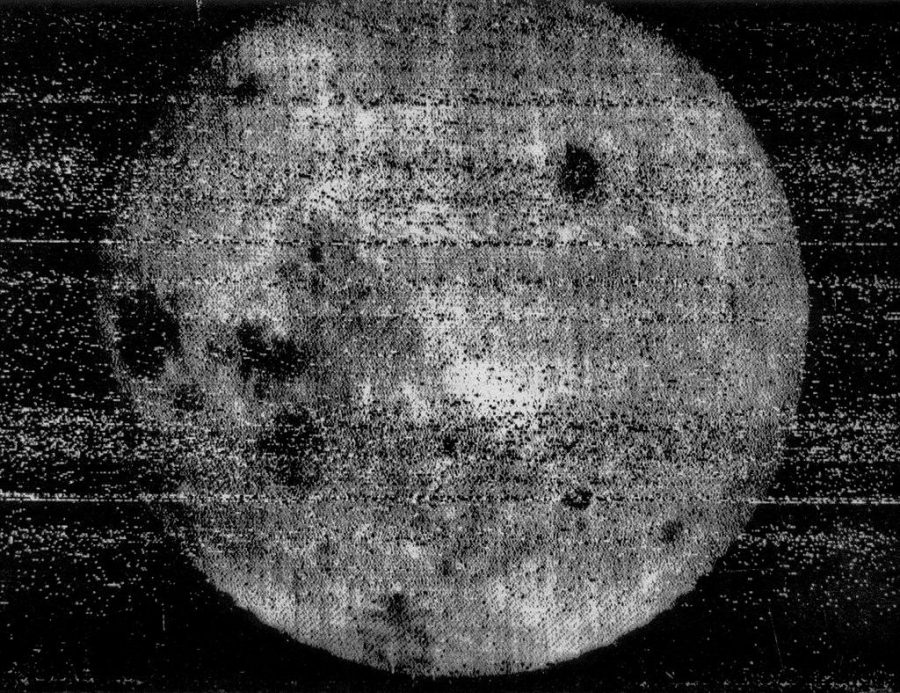

Sixty years ago, mankind got its very first glimpse of the far side of the Moon, so called because it faces away from the Earth. (And as astronomers like Neil DeGrasse Tyson have long taken pains to point out to Pink Floyd fans, it isn’t “dark.”) Taken by the Soviet Union, that first photo may not look like much today, especially compared to the high-resolution color images sent back from the surface itself by China’s Chang’e‑4 probe earlier this year. But with the technology of the late 1950s, even the technology commanded by the Soviets’ then-world-beating space program, the fact that it was taken at all seems not far short of miraculous. How did they do it?

“This photograph was taken by the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3, which was launched a month after the Luna 2 spacecraft became the first man-made object to impact on the surface of the Moon,” explains astronomer Kevin Hainline in a recent Twitter thread. “Luna 2 followed Luna 1, the first spacecraft to escape a geosynchronous Earth orbit.” Luna 3 was designed to take photographs of the Moon, hardly an uncomplicated prospect: “To take pictures you have to be stable on three-axes. You have to take the photographs remotely. AND you have to somehow transfer those pictures back to Earth.” The first three-axis stabilized spacecraft ever sent on a mission, Luna 3 “had to use a little photocell to orient towards the Moon so that now, while stabilized, it could take the pictures. Which it did. On PHOTOGRAPHIC FILM.”

Even those of us who took pictures on film for decades have started to take for granted the convenience of digital photography. But think back to all the hassle of traditional photography, then imagine making a robot carry them out in space. Once taken Luna 3’s photos “were then moved to a little CHEMICAL PLANT to DEVELOP AND DRY THEM.” (In other words, “Luna 3 had a little 1 Hour Photo inside.”) Then they continued into “a device that shone a cathode ray tube, like in an older TV, through them, towards a device that recorded the brightness and converted this to an electrical signal.” You can read about what happened then in more detail at Damn Interesting, where Alan Bellows describes how the spacecraft sent “the lightness and darkness information line-by-line via frequency-modulated analog signal — in essence, a fax sent over radio.”

Soviet Scientists could thus “retrieve one photographic frame every 30 minutes or so. Due to the distance and weak signal, the first images received contained nothing but static. In subsequent attempts in the following few days, an indistinct, blotchy white disc began to resolve on the thermal paper printouts at Soviet listening stations.” As Luna 3’s photos became clearer, they revealed, as Hainline puts it, that “the backside of the moon was SO WEIRD AND DIFFERENT” — covered in the craters, for example, which have become its visual signature. For a modern-day equivalent to this achievement, we might look not just to Chang’e‑4 but to the image of a black hole captured by the Event Horizon Telescope this past April — the one that led to an abundance of articles like “In Defense of the Blurry Black Hole Photo” and “We Need to Admit That the Black Hole Photo Isn’t Very Good.” Astrophotography has come a long way, but at least back in 1959 it didn’t produce quite so many takes.

Related Content:

Mankind’s First Steps on the Moon: The Ultra High Res Photos

8,400 Stunning High-Res Photos From the Apollo Moon Missions Are Now Online

How Scientists Colorize Those Beautiful Space Photos Taken By the Hubble Space Telescope

There’s a Tiny Art Museum on the Moon That Features the Art of Andy Warhol & Robert Rauschenberg

The Glorious Poster Art of the Soviet Space Program in Its Golden Age (1958–1963)

Wonderfully Kitschy Propaganda Posters Champion the Chinese Space Program (1962–2003)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.