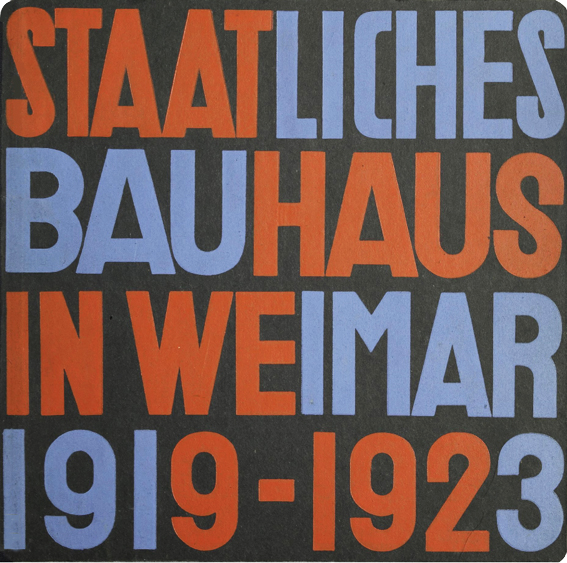

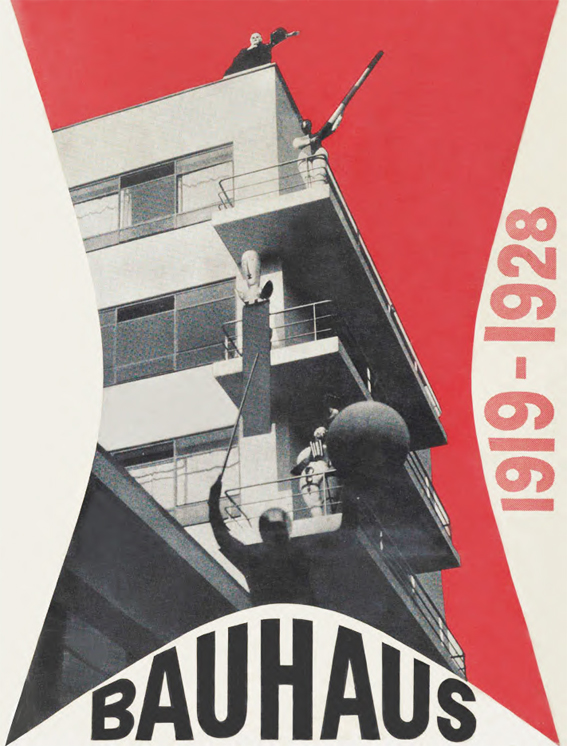

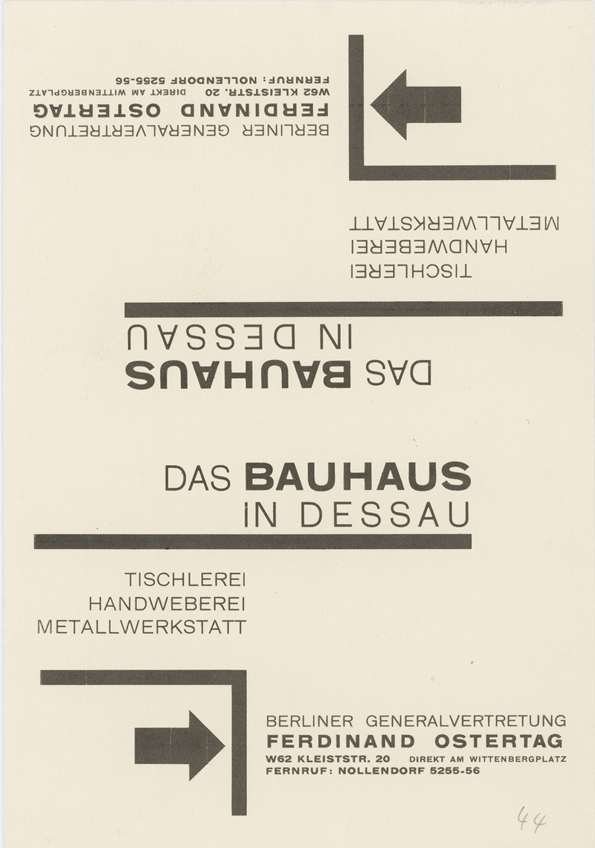

The Bauhaus, Barry Bergdoll writes in the New York Times of the German design school founded a century ago last month, “lasted just 14 years before the Nazis shut it down. And yet in that time it proved a magnet for much that was new and experimental in art, design and architecture — and for decades after, its legacy played an outsize role in changing the physical appearance of the daily world, in everything from book design to household lighting to lightweight furniture.” Celebrations of the Bauhaus’ centenary have taken many forms, including the documentary series Bauhaus World, the reimagining of modern corporate logos in the classic Bauhaus style, and now the free online resource Bauhaus Bookshelf.

Bauhaus Bookshelf creator Andrea Riegel calls the site “my modest contribution to #bauhaus100 and beyond: (almost) all Bauhaus books and journals in a virtual bookcase — with the possibility to download and take a closer look at the media and original sources, supplemented by short excerpts and contributions by Bauhaus people and contemporary witnesses or other content in context.”

In other worlds, you’ll find there not just the original Bauhaus manifesto, but sections on the series of “Bauhaus books” published by Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy; Bauhaus-associated creators and teachers like Paul Klee; Bauhaus advertising; the women of the Bauhaus (a subject previously featured here on Open Culture); and materials from the 1938 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art that introduced the Bauhaus to the world.

And 100 years after its founding, the world is still thinking about the Bauhaus, which, in Bergdoll’s words, “produced one of the most powerful expressions of a view that design was everything. It served, in a way, as the embassy of modernist design. But its success has often led to a reductionism in our understanding of the rich nexus of artistic movements that crisscrossed at the school itself, as well as the diverse developments it helped inspire.” For a better understanding of the Bauhaus, perhaps we must go back to the Bauhaus itself, not just in the sense of looking at the art, craft, design, and buildings its teachers and students produced, but the documents it issued on its mission and ideals. Whether in its English or German versions, Riegel’s Bauhaus Bookshelf serves as an intellectually and aesthetically stimulating place to find them.

Related Content:

32,000+ Bauhaus Art Objects Made Available Online by Harvard Museum Website

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.