We all know that civilizations, through the millennia, have had a way of rising and falling. But many of us don’t yet appreciate the fact that even after the fall, a civilization still has value — and can still come to harm. Archaeologists have used the traces left by bygone early cities, nations, and empires to gain an in-depth understanding of human history, but they can only continue doing so if the sites they study have the proper protection. The newest tool to advance that cause takes the form of the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East & North Africa (EAMENA) Database, a rich source of information, including satellite imagery and published reports, about the threatened archaeological sites and landscapes in that part of the world.

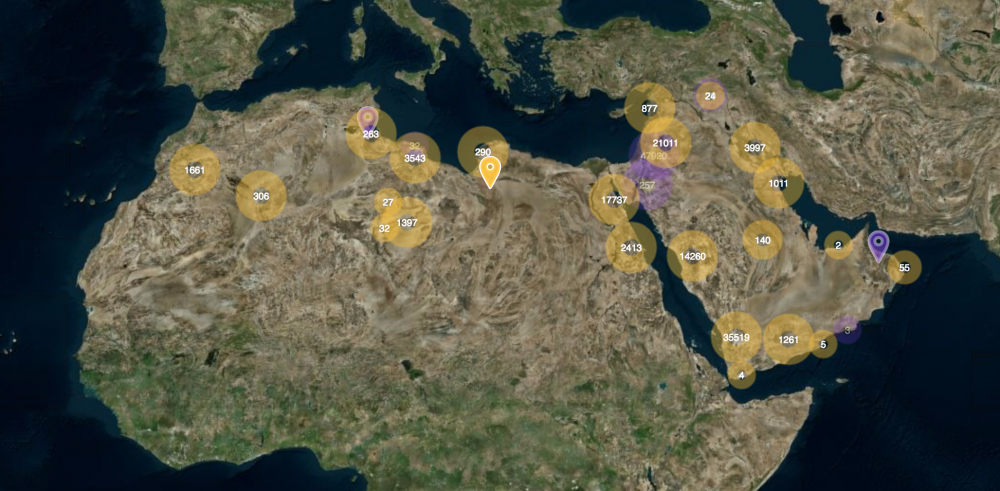

Based at the Universities of Oxford, Leicester, and Durham and built with the Getty Conservation Institute and World Monuments Fund’s open-source platform Arches, the English- and Arabic-Language Database uses, “an interactive map that traces the distribution of sites under threat,” writes Smithsonian’s Brigit Katz.

“You can click on select locales for information about how the sites were once used, and the types of disturbances that have occurred over the years. A pre-populated search function lets users browse through general categories — like ‘Pendants,’ a type of circular burial enclosure that is associated with some 700 sites in the database—and through specific locations.”

“Petra, Jericho, and the ancient port of Byblos are just three of the thousands of at-risk archaeological sites scattered across the Middle East and North Africa,” writes Hyperallergic’s Claire Voon. “Aside from the destruction wrought by wartime conflict, they also face damage from looting; agricultural practices; the construction of pipelines, refugee camps, and mining; and natural erosion.” In a press release announcing the project’s launch late last month, EAMENA’s director, Dr. Robert Bewley said that “not all damage and threats to the archaeology can be prevented, but they can be mitigated through the sharing of information and specialist skills.” And apart from the importance of preserving irreplaceable pieces of global cultural heritage, we might step back and consider that, the better we understand the trajectory of past civilizations, the more we can ensure a positive one for our own.

Click here to visit the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East & North Africa (EAMENA) Database.

Related Content:

Free Courses in Ancient History, Literature & Philosophy

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E.

How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation

Visit Pompeii (also Stonehenge & Versailles) with Google Street View

Beer Archaeology: Yes, It’s a Thing

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.