“Real news, fake news, who cares, it’s all the same, am I right?”

… Not to make light of an existential crisis in journalism and the public trust—a disturbing development. Cynicism threatens to erode the very foundations of… well, ring your own alarm bell. Perhaps it’s time we (re)drew some hard lines around what we mean by the word “news.”

How to do that? I leave it to the experts—professors of journalism, reporters and archivists and historians who do the hard work of constructing genealogies and taxonomies of news, discovering its mutations and dead ends.

Journalism libraries around the country fulfill the needs of these scholars, as does the Library of Congress. But if you really want to dig into a comprehensive collection—one that bests even the august Federal government library (sort of)—you’ll need to visit the website of one Tom Tryniski, private citizen, retired “computer expert,” writes Jim Epstein at Reason, and dedicated amateur, “working alone.”

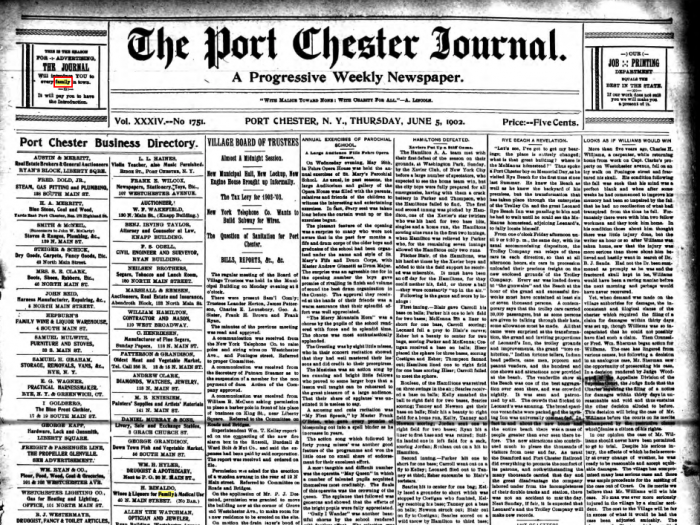

This being Reason, the preserve of “free minds and free markets,” you can expect a good bit of crowing about the entrepreneurial spirit of Tryniski’s accomplishment—an archive of 37,439,000 historic newspaper pages from the U.S. and Canada, “orders of magnitude bigger and more popular than one created by a federal bureaucracy with millions of dollars to spend.” The video above says it succinctly in a tagline: “Amateur beats gov’t at digitizing newspapers.”

Should you take an interest in what Tryniski—the sole employee of Old Fulton New York Postcards—spends, Epstein provides a full accounting of the site’s impressively meager operating budget. Should you wonder where the LoC’s money goes, and why it uses so many more resources than one retiree, you may wish to do your own comparison between Tryniski’s site and the Feds’ online news archive, Chronicling America. (And maybe pay their place a visit in the flesh.) There’s more to a library than numbers of pages and views.

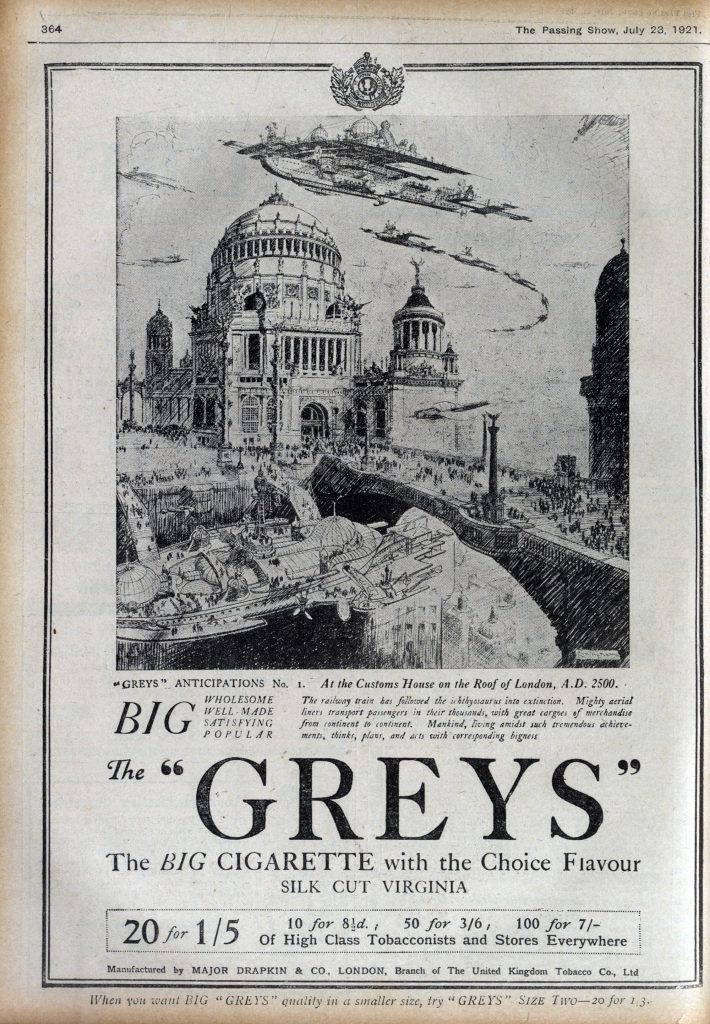

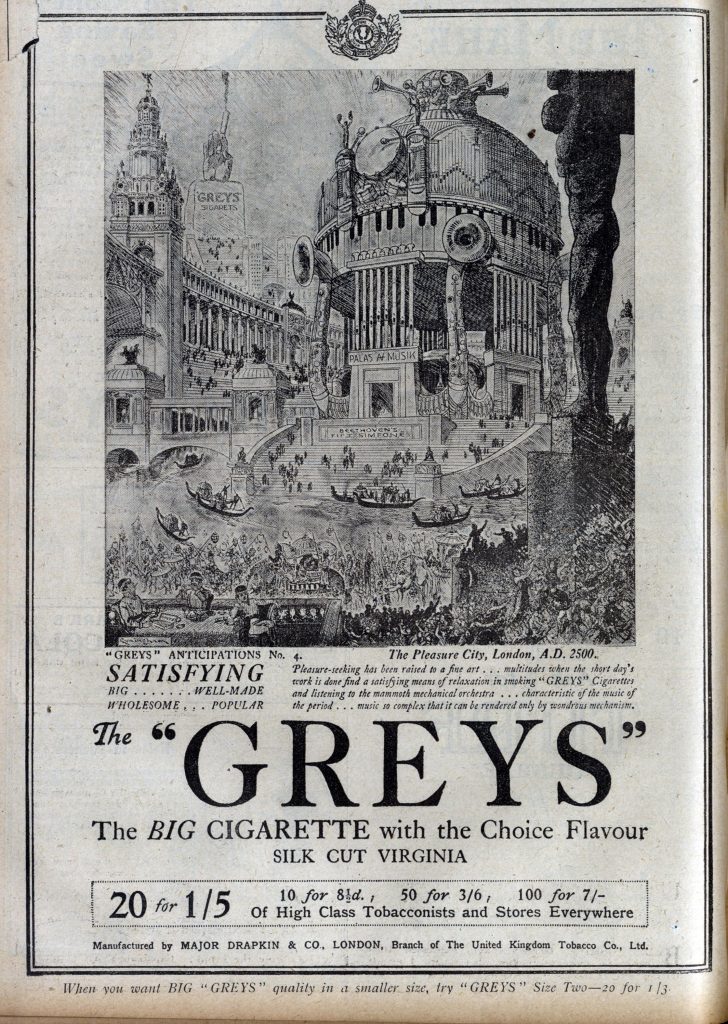

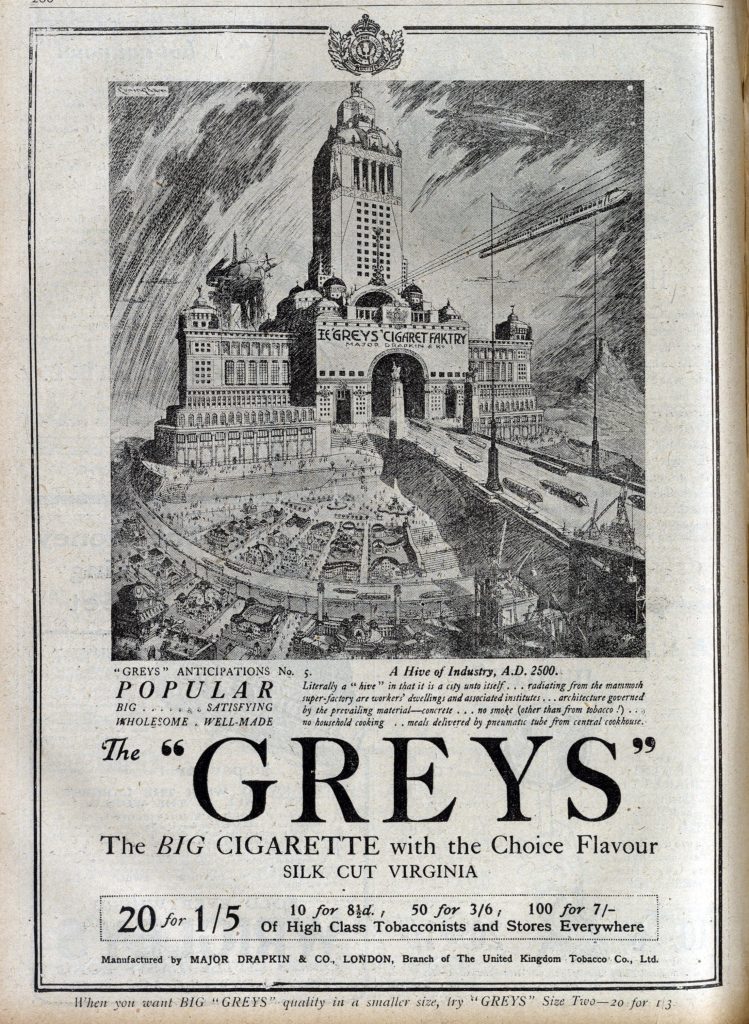

In some ways, it’s not a fair comparison. Tryniski may be a computer expert, but he’s not a web designer (or he’s an ornery, old-school purist). His site (last updated in 2014), with its frames and heavy use of Flash and GIFs, reflects the web’s anarchic 90s heyday. And where the LoC’s site chronicles all of America, Tryniski’s mostly sticks to New York, with local papers like The Port Chester Journal (above) represented heavily.

That said, the site’s search functions are much cooler than those of glossier competitors, with options for “fuzzy searching,” “phonic searching” (for those of us who can’t spell), “and “user-defined synonyms.” Tryniski also knows his way around microfilm and a microfilm scanner, despite (we’re expressly told for some reason in the video and Epstein’s article) his being “a high school graduate.”

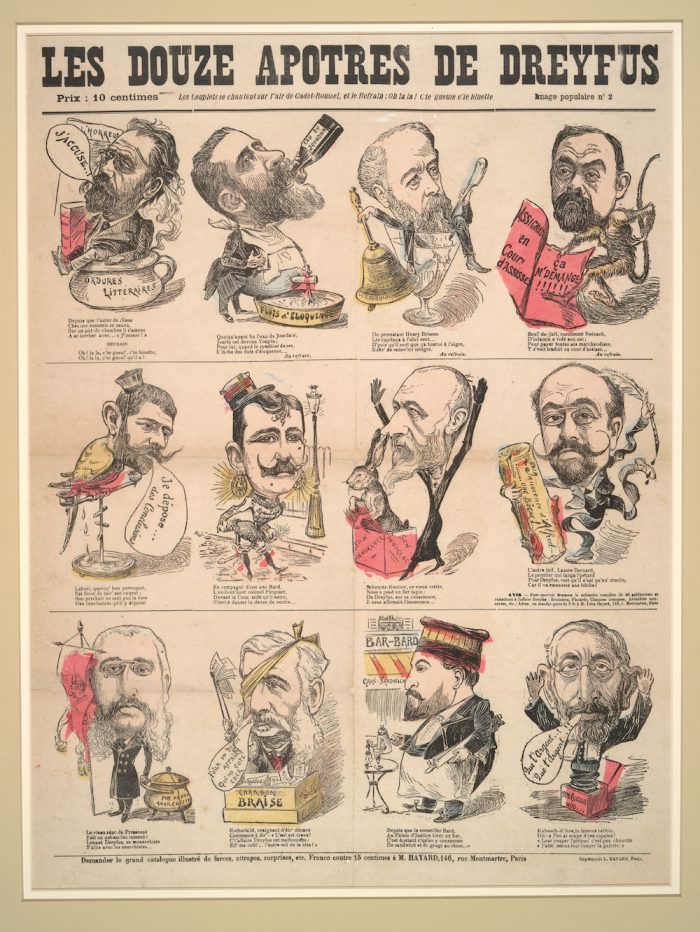

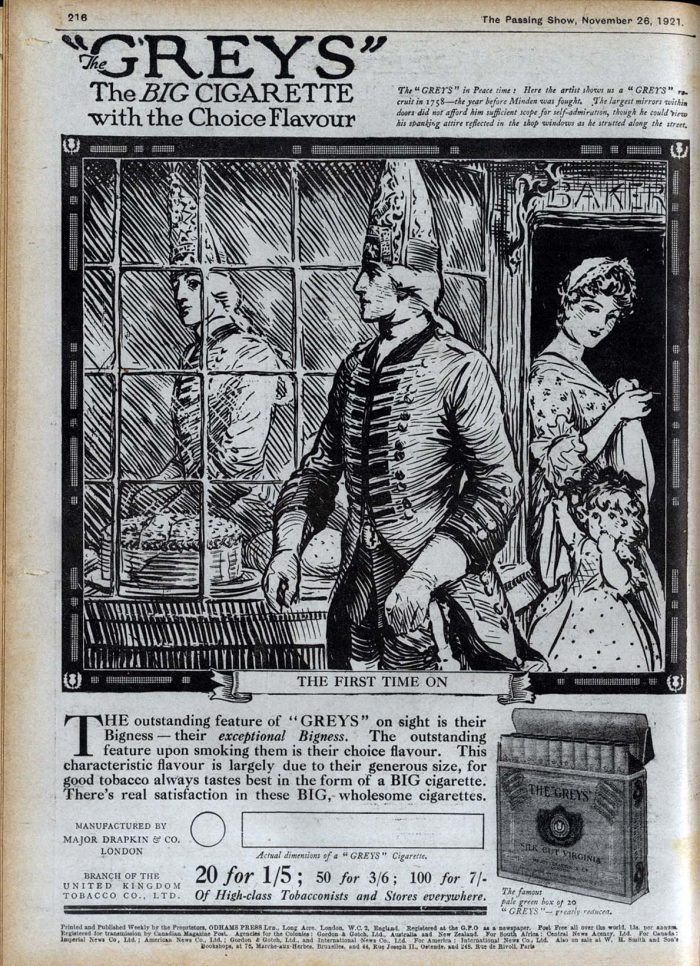

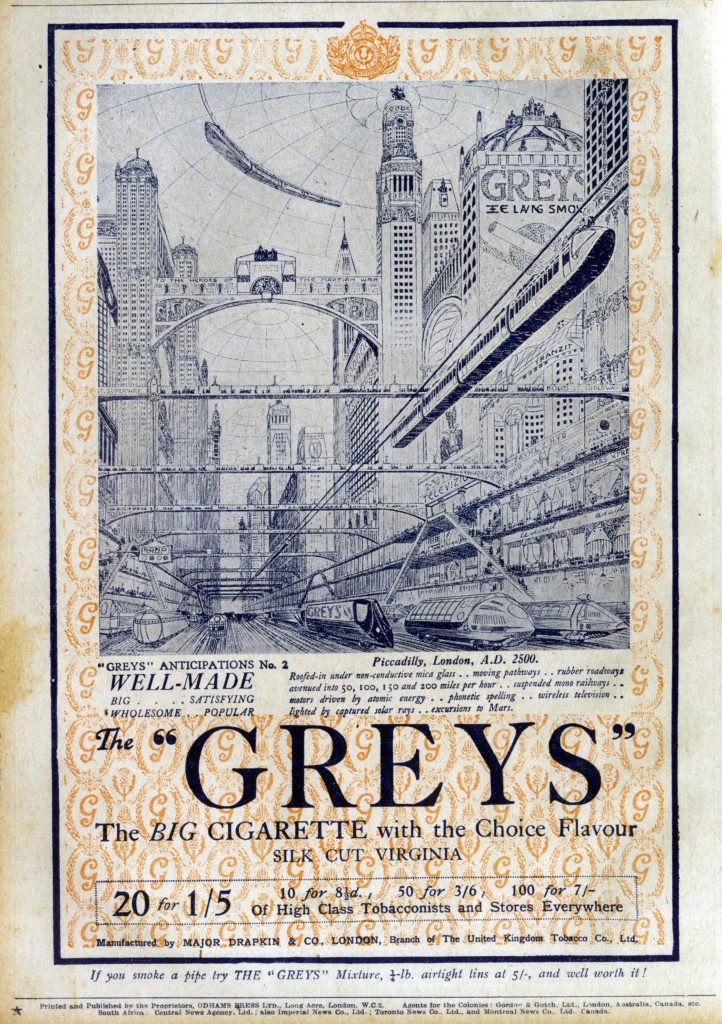

In this triumph of the everyman story, however, Tryniski does not introduce his own collection with fulminations of the “old man shakes fist at” variety. Instead he describes his collection as a means of time travel. “It’s the day-to-day life,” he says, “that you could not imagine today. Reading the actual newspaper seems to bring it back into current context. People… sit there and it’s like, they move back into that time, and it’s like they’re living in the same time as their grandparents and great-grandparents.”

Nobody needs to fix journalism, libraries, or federal spending to have this experience, and it’s one everyone should have—whether by traveling through the pages of old newspapers or a family trove of photos and letters. History can seem like little more than a story we tell ourselves about the past, but the primary documents have tales to tell that we could never imagine.

Learn more about Tryniski’s collection at Reason, and visit the quirky, deceptively fulsome Old Fulton NY Post Cards (named as such because the site began as a scanned collection of postcards from Tryniski’s hometown of Fulton, NY). You’ll find in its charmingly clunky environs a fascinating repository of vintage news and photos. And remember, “If you did not read about it on Old Fulton NY Post Cards, IT DID NOT HAPPEN!!!”

Related Content:

From the Annals of Optimism: The Newspaper Industry in 1981 Imagines its Digital Future

Archive of Hemingway’s Newspaper Reporting Reveals Novelist in the Making

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness