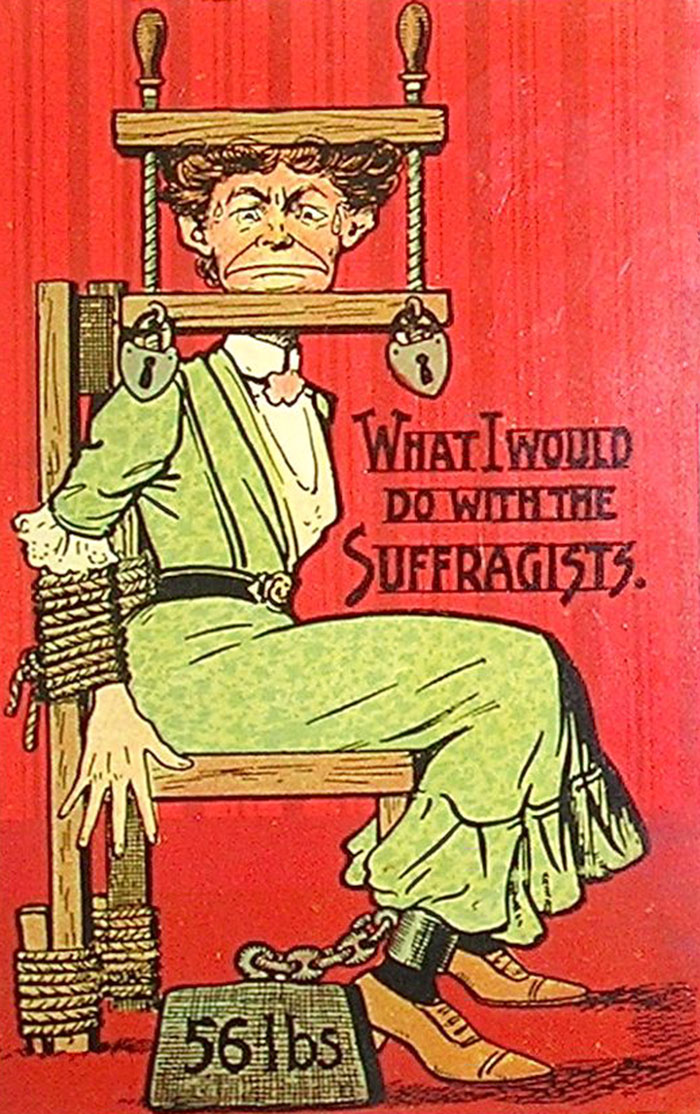

I’ve heard it again and again. The now President-elect made vicious and belittling attacks on African-Americans, Muslims, immigrants, women, the disabled, etc. during the campaign season (and for several decades before), but he didn’t mean it. And I have many questions. For example, why should anyone assume—given the history of country after country after country—that a bullying nativist autocrat doesn’t mean what he says?

We know celebrity breeds trivialization. But we also know well that in some of the most famous—but by no means only—cases of demagogues who rose to power with hate speech, the rhetoric quickly turned to many years of incomprehensible, yet calculated, brutality. At least in the U.S., hardly anyone believed that the melodramatic vitriol Hitler and Mussolini spat at scapegoats of all kinds, especially Jews, should be taken very seriously.

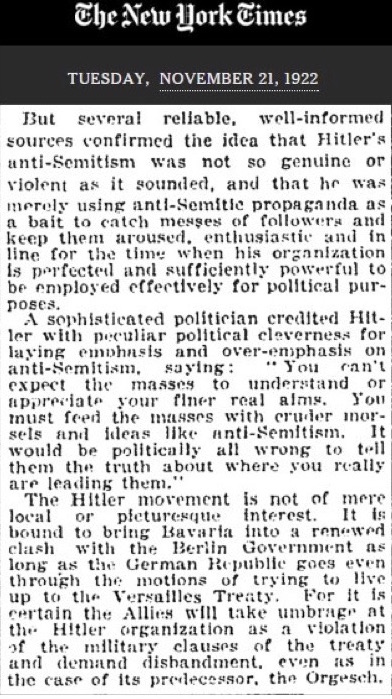

In 1922—at the dawn of Hitler’s budding nationalist movement—The New York Times published its first profile, and explained his demagoguery away. The article, titled “New Popular Idol Rises in Bavaria,” begins with several alarming subheadings: “Hitler credited with extraordinary powers of swaying crowds to his will,” “forms gray-shirted army… They obey orders implicitly,” “Leader a reactionary,” “Anti-Red and Anti-Semitic.” It then goes on to undermine these charges.

According to “several reliable, well-informed [unnamed] sources,” we’re told, “Hitler’s anti-Semitism was not so genuine or violent as it sounded,” though “the Hitler movement is not of a mere local or picturesque interest.”

He was merely using anti-Semitic propaganda as a bait to catch masses of followers and keep them aroused, enthusiastic and in line for the time when his organization is perfected and sufficiently powerful to be employed effectively for political purposes.

What purposes? The paper quotes one admiring “sophisticated politician” as saying, “You can’t expect the masses to understand or appreciate your finer real aims. You must feed the masses with cruder morsels and ideas like anti-Semitism. It would be politically all wrong to tell them the truth about where you really are leading them.” Where might this be? The shadowy source did not say. We cynically expect all politicians to lie, to feed us “cruder morsels.” But assuming that racism, bigotry, and scapegoating—whether sincere or not—will go down so easily with so many people constitutes a very dark view of “the masses.”

Ten years later, after Hitler was released from prison for treason and had begun his candidacy for president, many, even more complimentary, articles would follow—as Rafael Medoff documents in The Daily Beast—all the way up to Time magazine’s naming him “Man of the Year” for 1938. “Why did many mainstream American newspapers portray the Hitler regime positively,” asks Medoff, “especially in its early months? How could they publish warm human-interest stories about a brutal dictator? Why did they excuse or rationalize Nazi anti-Semitism? These are questions that should haunt the conscience of U.S. journalism to this day.”

One reporter in a 1933 Christian Science Monitor dispatch from Germany informed his readers that “the train arrived punctually”—indulging a trope about fascists making the “trains run on time” that has astonishingly come back in circulation via former Cincinnati mayor Ken Blackwell. “Traffic was well regulated.” The correspondent found “not the slightest sign of anything unusual afoot.” The word we often hear for what happened during the 30s is “normalization,” a process by which the most harrowing portents were blended into the landscape, rendered signs of nothing “unusual afoot.”

The normalization of Nazism in Germany involved a tremendous propaganda effort, much of it aimed at children. In the U.S., the press seemed more than willing to turn an ethno-nationalist movement with frightening—and plainly stated—objectives into an ordinary, rational state actor. Anti-Semitism was described as legitimate political resentment or reasonable anger at German Jews’ “commercial clannishness.” Somehow the victims of Nazism had to be responsible for their own murder and persecution. “There must be some reason,” wrote The Christian Century in an April, 1933 editorial, “other than race or creed—just what is that reason?” Few people, it seems, could or would allow themselves to imagine that the new German Führer actually meant what he said.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Free Online History Courses, a subset of our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

George Orwell Reviews Mein Kampf: “He Envisages a Horrible Brainless Empire” (1940)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.