Much has been made of Mark Twain’s financial problems—the imprudent investments and poor management skills that forced him to shutter his large Hartford estate and move his family to Europe in 1891. An early adopter of the typewriter and long an enthusiast of new science and technology, Twain lost the bulk of his fortune by investing huge sums—roughly eight million dollars total in today’s money—on a typesetting machine, buying the rights to the apparatus outright in 1889. The venture bankrupted him. The machine was overcomplicated and frequently broke down, and “before it could be made to work consistently,” writes the University of Virginia’s Mark Twain library, “the Linotype machine swept the market [Twain] had hoped to corner.”

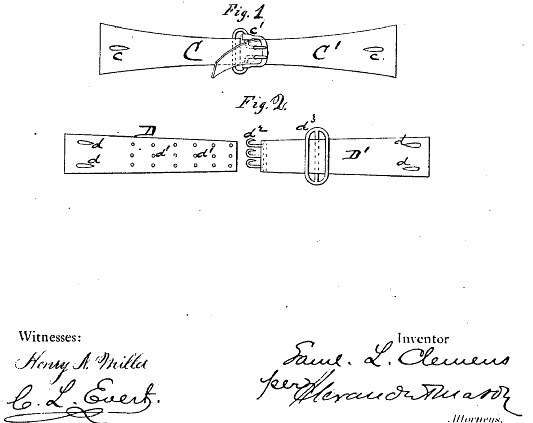

Twain’s seemingly blind enthusiasm for the ill-fated machine makes him seem like a bungler in practical matters. But that impression should be tempered by the acknowledgement that Twain was not only an enthusiast of technology, but also a canny inventor who patented a few technologies, one of which is still highly in use today and, indeed, shows no signs of going anywhere. I refer to the ubiquitous elastic hook clasp at the back of nearly every bra, an invention Twain patented in 1871 under his given name Samuel L. Clemens. (View the original patent here.) You can see the diagram for his invention above. Calling it an “Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments,” Twain made no mention of ladies’ undergarments in his patent application, referring instead to “the vest, pantaloons, or other garment upon which my strap is to be used.”

The device, writes the US Patent and Trademark Office, “was not only used for shirts, but underpants and women’s corsets as well. His purpose was to do away with suspenders, which he considered uncomfortable.” (At the time, belts served a mostly decorative function.) Twain’s inventions tended to solve problems he encountered in his daily life, and his next patent was for a hobbyist set of which he himself was a member. After the soon-to-be bra strap, Twain devised a method of improvement in scrapbooking, an avid pursuit of his, in 1873.

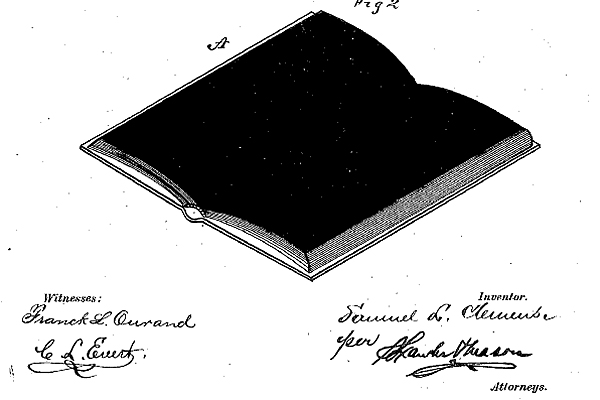

Previously, scrapbooks were assembled by hand-gluing each item, which Twain seemed to consider an overly laborious and messy process. His invention—writes The Atlantic in part of a series they call “Patents of the Rich and Famous”—involved “two possible self-adhesive systems,” similar to self-sealing envelopes, in which, as his patent states, “the surfaces of the leaves whereof are coated with a suitable adhesive substance covering the whole or parts of the entire surface.” (See the less-than-clear diagram for the invention above.) The scrapbooking device proved “very popular,” writes the US Patent Office, “and sold over 25,000 copies.”

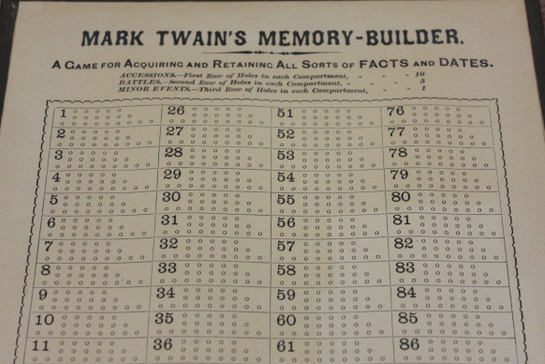

Twain obtained his final patent in 1885 for a “Game Apparatus” that he called the “Memory-Builder” (see it above). The object of the game was primarily educational, helping, as he wrote, to “fill the children’s heads with dates without study.” As we reported in a previous post, “Twain worked out a way to play it on a cribbage board converted into a historical timeline.” Unlike his first two inventions, the game met with no commercial success. “Twain sent a few prototypes to toy stores in 1891,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate, “but there wasn’t very much interest, so the game never went into production.” Nonetheless, we still have Twain to thank, or to damn, for the bra strap, an invention of no small importance.

Twain himself seems to have had some contradictory attitudes about his role as an inventor, and of the singular recognition granted to individuals through patent law. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the US Patent Office claims that Twain “believed strongly in the value of the patent system” and cites a passage from A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court in support. But in a letter Twain wrote to Helen Keller in 1903, he expressed a very different view. “It takes a thousand men to invent a telegraph, or a steam engine, or a phonograph, or a telephone or any other important thing,” Twain wrote, “and the last man gets the credit and we forget the others. He added his little mite—that is all he did. These object lessons should teach us that ninety-nine parts of all things that proceed from the intellect are plagiarisms, pure and simple.”

Related Content:

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

Play Mark Twain’s “Memory-Builder,” His Game for Remembering Historical Facts & Dates

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness