Bear in mind, fantasy baseball fans, that with the season about to start up again, you shouldn’t feel like you have to take any grief for enjoying the game. It counts among its enthusiasts no less a luminary than Jack Kerouac, author of On The Road and The Dharma Bums, and he didn’t just enjoy it, he arguably invented it. The New York Public library devoted an exhibition to Kerouac’s near-lifelong hobby called “Fantasy Sports and the King of the Beats,” revealing how the writer invented an elaborate means of experiencing the joys of America’s National Pastime all on his own.

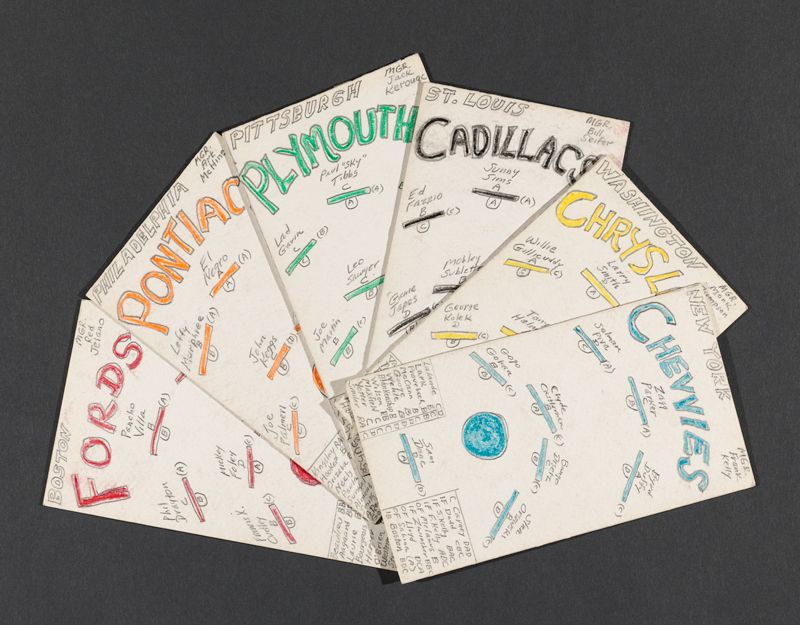

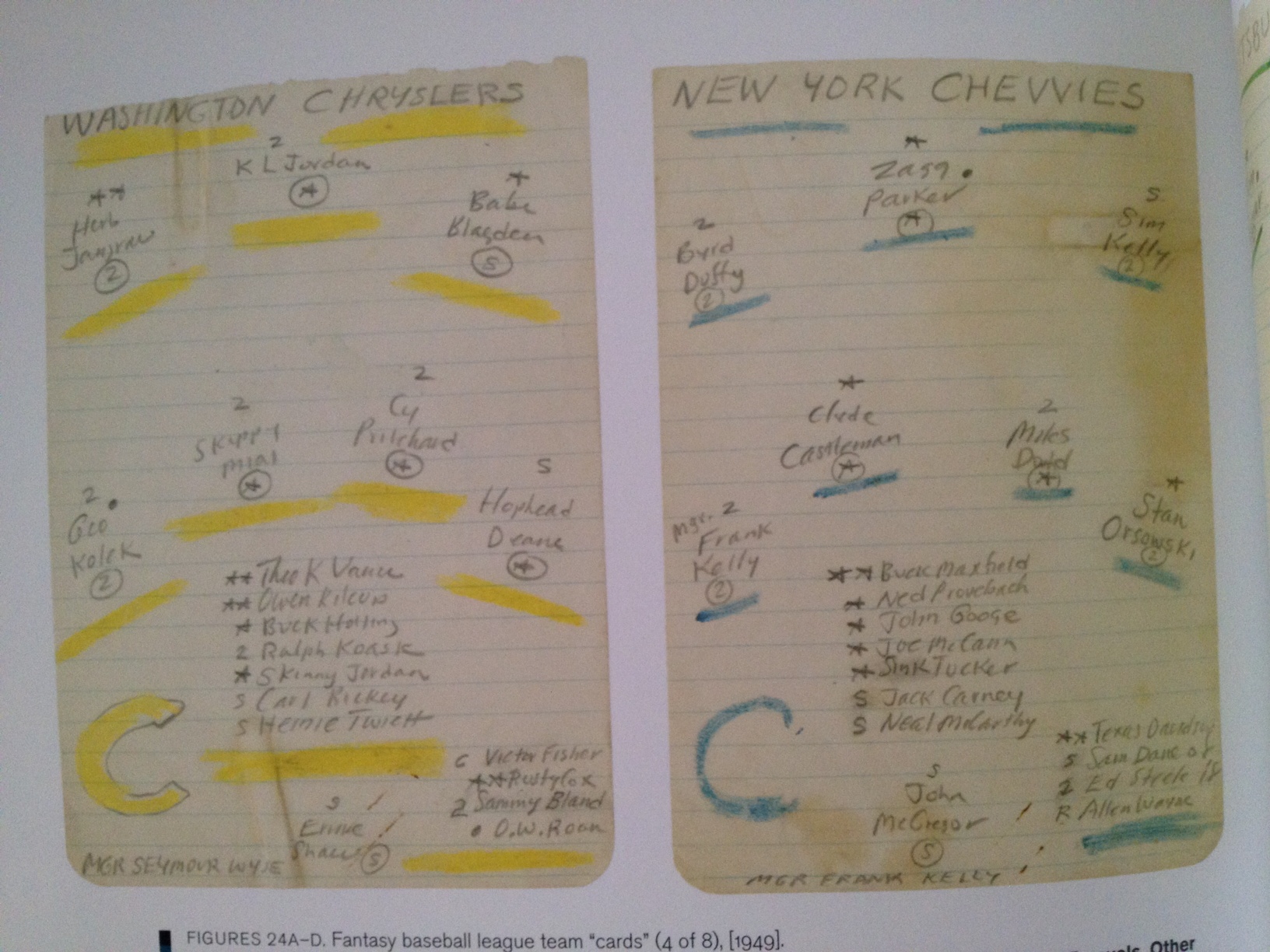

He also created an entire world of imagined teams, imagined players, and imagined athletic and financial dramas as well. The New York Times’ Charles McGrath writes that Kerouac “obsessively played a fantasy baseball game of his own invention, charting the exploits of made-up players like Wino Love, Warby Pepper, Heinie Twiett, Phegus Cody and Zagg Parker, who toiled on imaginary teams named either for cars (the Pittsburgh Plymouths and New York Chevvies, for example) or for colors (the Boston Grays and Cincinnati Blacks).”

Rather than a distraction from his writing, all this proved to be “ideal training for a would-be author,” since his version of fantasy baseball also required him come up with voluminous coverage of the action which “imitates the overheated, epithet-studded sportswriting of the day.” Fantasy baseball has since turned into a national (and, to an extent, even international) phenomenon, but the game that thousands of baseball nuts play today, which uses the real statistics of non-made-up baseball players on actual teams, doesn’t demand nearly as much creativity as did the one Kerouac played by himself.

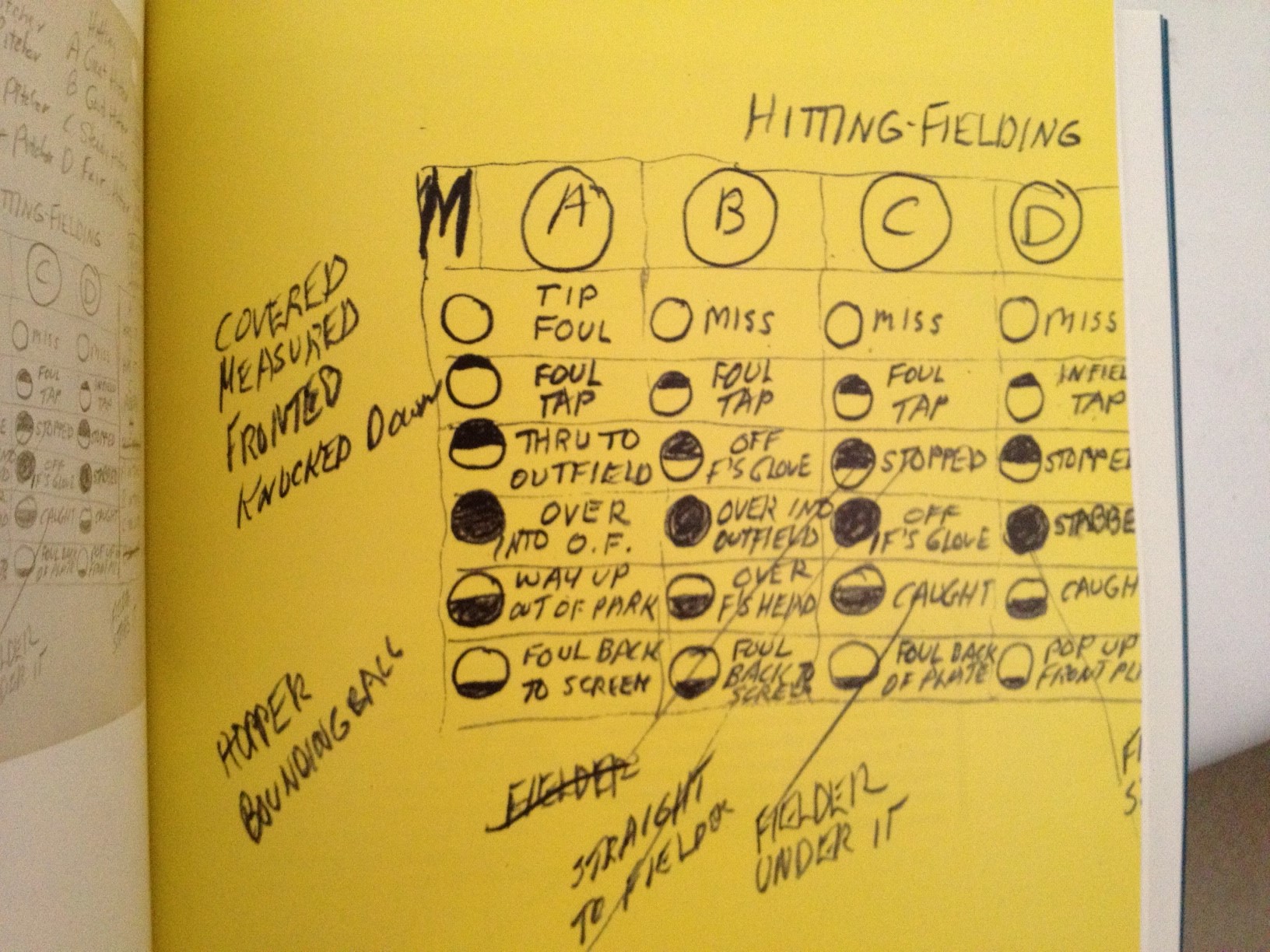

Kerouac’s fantasy baseball even achieved a kind of prescience, not just in terms of prefiguring fantasy baseball as we now know it, but events in baseball proper: “As befitting the author of On the Road, the narrator of which journeys three times to California with a pilgrim’s zeal,” says the NYPL’s site, Kerouac “brought his fantasy baseball league to California. In this instance, fantasy trumped reality, since Kerouac’s California teams are established at least one year before the Dodgers and Giants abandoned New York for California.” One wonders what the victories and tribulations of the Plymouths and the Chevvies, the Grays and the Blacks, their fates decided with marbles, sticks, complex diagrams, and cards full of now-indecipherable symbols, might foretell about the fate of Major League Baseball’s teams this coming season.

Related Content:

Jack Kerouac’s Hand-Drawn Map of the Hitchhiking Trip Narrated in On the Road

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose

Jack Kerouac Reads from On the Road (1959)

Jack Kerouac’s Naval Reserve Enlistment Mugshot, 1943

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.