Any serious reader of Haruki Murakami — and even most of the casual ones — will have picked up on the fact that, apart from the work that has made him quite possibly the world’s most beloved living novelist, the man has two passions: running and jazz. In his memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, he tells the story of how he became a runner, which he sees as inextricably bound up with how he became a writer. Both personal transformations occurred in his early thirties, after he sold Peter Cat, the Tokyo jazz bar he spent most of the 1970s operating. Yet he hardly put the music behind him, continuing to maintain a sizable personal record library, weave jazz references into his fiction, and even to write the essay collections Portrait in Jazz and Portrait in Jazz 2.

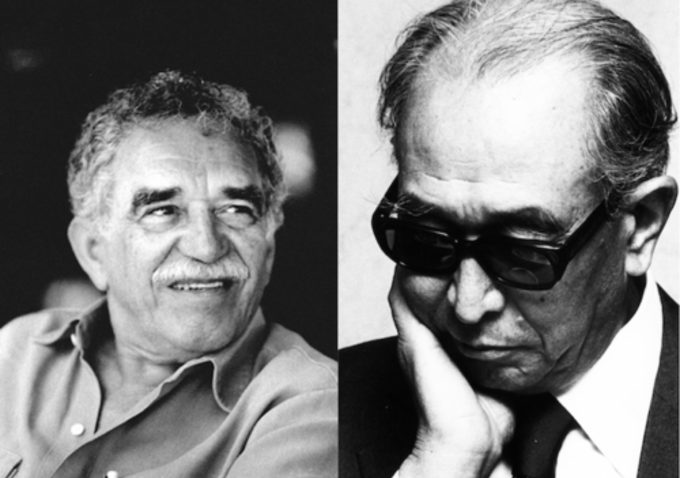

Image comes from Ilana Simons’ animated introduction to Murakami

“I had my first encounter with jazz in 1964 when I was 15,” Murakami writes in the New York Times. “Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers performed in Kobe in January that year, and I got a ticket for a birthday present. This was the first time I really listened to jazz, and it bowled me over. I was thunderstruck.” Though unskilled in music himself, he often felt that, in his head, “something like my own music was swirling around in a rich, strong surge. I wondered if it might be possible for me to transfer that music into writing. That was how my style got started.”

He found writing and jazz similar endeavors, in that both need “a good, natural, steady rhythm,” a melody, “which, in literature, means the appropriate arrangement of the words to match the rhythm,” harmony, “the internal mental sounds that support the words,” and free improvisation, wherein, “through some special channel, the story comes welling out freely from inside. All I have to do is get into the flow.”

With Peter Cat long gone, fans have nowhere to go to get into the flow of Murakami’s personal jazz selections. Still, at the top of the post, you can listen to a playlist of songs mentioned in Portrait in Jazz, featuring Chet Baker, Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Bill Evans, and Miles Davis. (You can find another extended playlist of 56 songs here.) Should you make the trip out to Tokyo, you can also pay a visit to Cafe Rokujigen, profiled in the short video just above, where Murakami readers congregate to read their favorite author’s books while listening to the music that, in his words, taught him everything he needed to know to write them. And elsewhere on the very same subway line, you can also visit the old site of Peter Cat: just follow in the footsteps taken by A Geek in Japan author Héctor García, who set out to find it after reading Murakami’s reminiscences in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. And what plays in the great eminence-outsider of Japanese letters’ earbuds while he runs? “I love listening to the Lovin’ Spoonful,” he writes. Hey, you can’t spin to Thelonious Monk all the time.

Related Content:

Murakami, Japan’s Jazz and Baseball-Loving Postmodern Novelist

In Search of Haruki Murakami, Japan’s Great Postmodernist Novelist

Haruki Murakami Translates The Great Gatsby, the Novel That Influenced Him Most

1959: The Year that Changed Jazz

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.