Why study a language like French? For the unparalleled pleasure, of course, of reading a beloved, respected, and enduring novel like Madame Bovary in the original — or so literarily inclined Francophiles might argue. After all, they’d rhetorically ask, can you really say you’ve read the book if you haven’t actually read the very same words Gustave Flaubert wrote? But now, literarily inclined Francophiles who also have an enthusiasm for the web (not an overwhelmingly large group, wags may point out) can insist that you haven’t really read Madame Bovary unless you’ve read it all in the original: all 4,500 pages of it. Yes, the French do tend to write longer sentences than most, but that impressive length has less to do with a national literary style than with thoroughgoing completism, an impulse that brings together all of the 1856 novel’s originally published pages as well as all of those cut, censored, or revised, free to read online at bovary.fr.

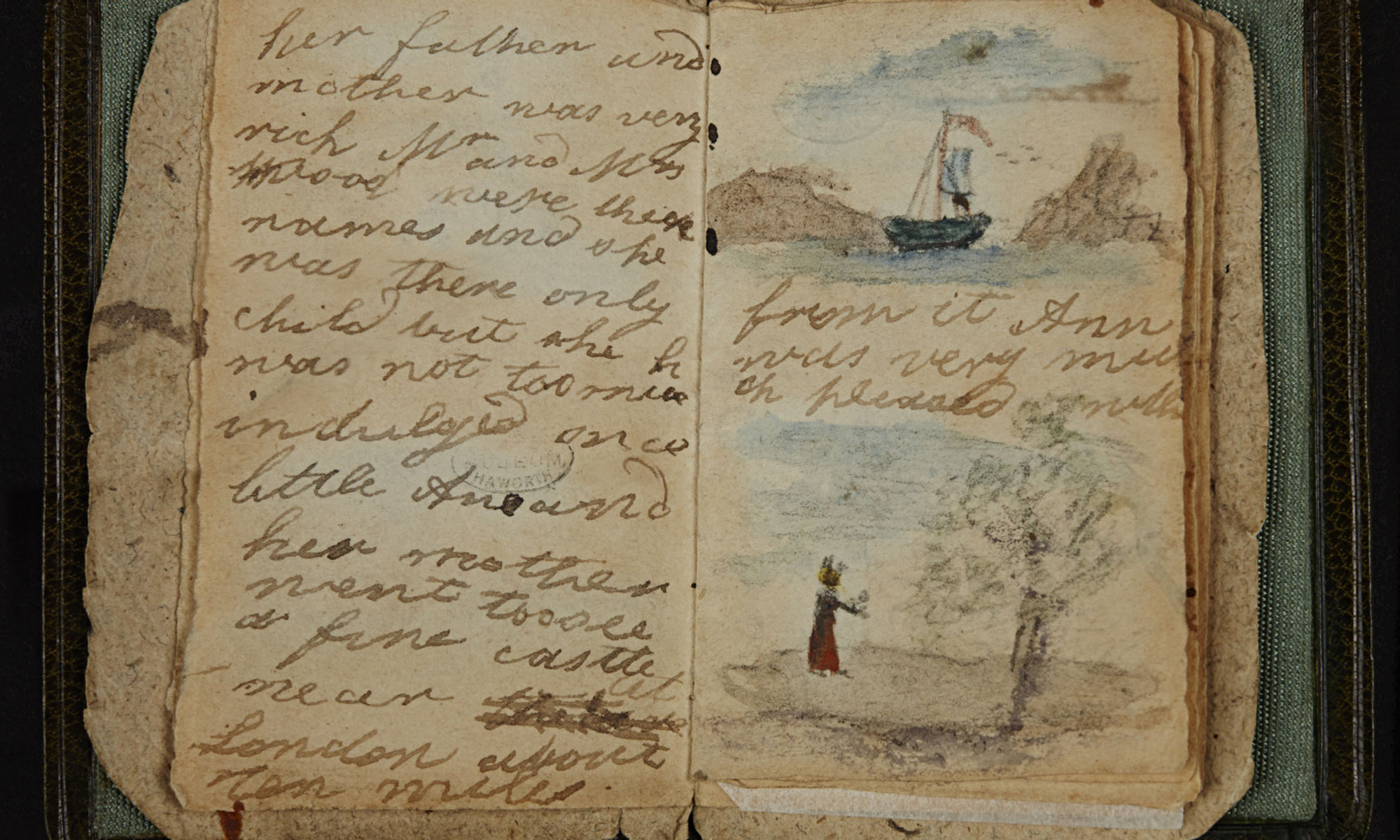

“After a marathon effort of transcription by 130 volunteers from all over the world, including a cleaning lady, an oil prospector and several teenagers,” writes the Independent’s John Lichfield, “all the variants of Gustave Flaubert’s masterpiece can be consulted on a new website. This is believed to be the first time that the complete process of creation, and publication, of a classic novel has been made available on the internet,” much less on a site that “contains not only the published text and images of the barely legible manuscripts but interactive controls which allow the reader to re-instate passages corrected or cut by Flaubert or his publishers.” Despite this unprecedentedly vast and accessible trove of Madame Bovary resources, struggles over the proper interpretation of the once-scandalous novel will doubtless only continue, not only at the level of just which word Flaubert intended to write on the fourth draft of a particularly crucial paragraph, but at the level of whether to consider the whole book tragedy, comedy, or something in between. Enter the Madame Bovary Archive here.

Related Content:

As Pride and Prejudice Turns 200, Read Jane Austen’s Manuscripts Online

The Online Emily Dickinson Archive Makes Thousands of the Poet’s Manuscripts Freely Available

James Joyce Manuscripts Online, Free Courtesy of The National Library of Ireland

Mary Shelley’s Handwritten Manuscripts of Frankenstein Now Online for the First Time

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.