“Eudora Welty is one of the reasons that you thank God you know how to read,” writes an online reviewer of her autobiography One Writer’s Beginnings. It’s a sentiment with which I could not agree more. Whether in memoir, short story, or novel, Welty—winner of nearly every literary prize save the Nobel—speaks with the most highly individual of voices. (Welty once told a Paris Review interviewer that she doesn’t read anyone for “kindredness.”) Her prose, so attuned to its own rhythms, so confidently venturing into new realms of thought, seems to surprise even her. Indeed, teachers of writing could hardly do better than assign Welty to illustrate the elusive concept of “voice”—it’s a writerly quality she mastered early, or perhaps always possessed.

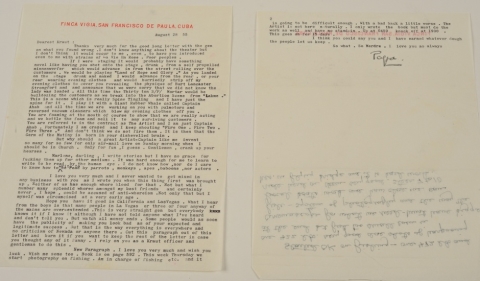

Take the 1933 letter below in which she introduces herself, a young postgraduate of 23, to The New Yorker in hopes of securing a position doing… well, whatever. She proposes “drum[ming] up opinions” on books and film, but only at the rate of “a little paragraph each morning—a little paragraph each night” (though she would “work like a slave” if asked). She also offers to replace cartoonist (and author of “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”) James Thurber “in case he goes off the deep end.” The letter brims with winsome self-confidence and breezy optimism, as well as the unselfconscious self-awareness she makes look so easy: “That shows you how my mind works,” she writes, “quick, and away from the point.” The magazine staff, points out Shane Parrish of Farnam Street, “ignored her plea […] missing the obvious talent,” though of course they would begin publishing her stories just a few years later.

Read the letter in full below and marvel at how anyone could reject such a delightfully enthusiastic candidate (she would do just fine as a junior “publicity agent” for the WPA).

March 15, 1933

Gentlemen,

I suppose you’d be more interested in even a sleight‑o’-hand trick than you’d be in an application for a position with your magazine, but as usual you can’t have the thing you want most.

I am 23 years old, six weeks on the loose in N.Y. However, I was a New Yorker for a whole year in 1930–31 while attending advertising classes in Columbia’s School of Business. Actually I am a southerner, from Mississippi, the nation’s most backward state. Ramifications include Walter H. Page, who, unluckily for me, is no longer connected with Doubleday-Page, which is no longer Doubleday-Page, even. I have a B.A. (’29) from the University of Wisconsin, where I majored in English without a care in the world. For the last eighteen months I was languishing in my own office in a radio station in Jackson, Miss., writing continuities, dramas, mule feed advertisements, santa claus talks, and life insurance playlets; now I have given that up.

As to what I might do for you — I have seen an untoward amount of picture galleries and 15¢ movies lately, and could review them with my old prosperous detachment, I think; in fact, I recently coined a general word for Matisse’s pictures after seeing his latest at the Marie Harriman: concubineapple. That shows you how my mind works — quick, and away from the point. I read simply voraciously, and can drum up an opinion afterwards.

Since I have bought an India print, and a large number of phonograph records from a Mr. Nussbaum who picks them up, and a Cezanne Bathers one inch long (that shows you I read e. e. cummings I hope), I am anxious to have an apartment, not to mention a small portable phonograph. How I would like to work for you! A little paragraph each morning — a little paragraph each night, if you can’t hire me from daylight to dark, although I would work like a slave. I can also draw like Mr. Thurber, in case he goes off the deep end. I have studied flower painting.

There is no telling where I may apply, if you turn me down; I realize this will not phase you, but consider my other alternative: the U of N.C. offers for $12.00 to let me dance in Vachel Lindsay’s Congo. I congo on. I rest my case, repeating that I am a hard worker.

Truly yours,

Eudora Welty

Welty’s letter appears alongside dozens more remarkable missives in the beautiful new book, Letters of Note: An Eclectic Collection of Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience.

via Farnam Street/Brain Pickings

Related Content:

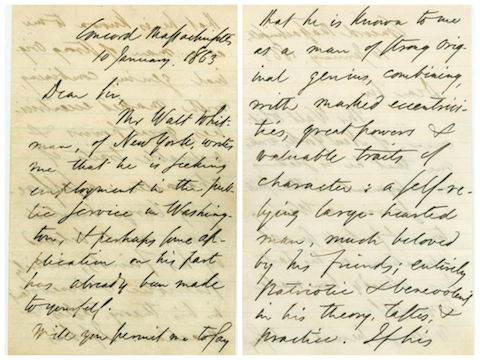

Ralph Waldo Emerson Writes a Job Recommendation for Walt Whitman (1863)

Read Rejection Letters Sent to Three Famous Artists: Sylvia Plath, Kurt Vonnegut & Andy Warhol

Gertrude Stein Gets a Snarky Rejection Letter from Publisher (1912)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.