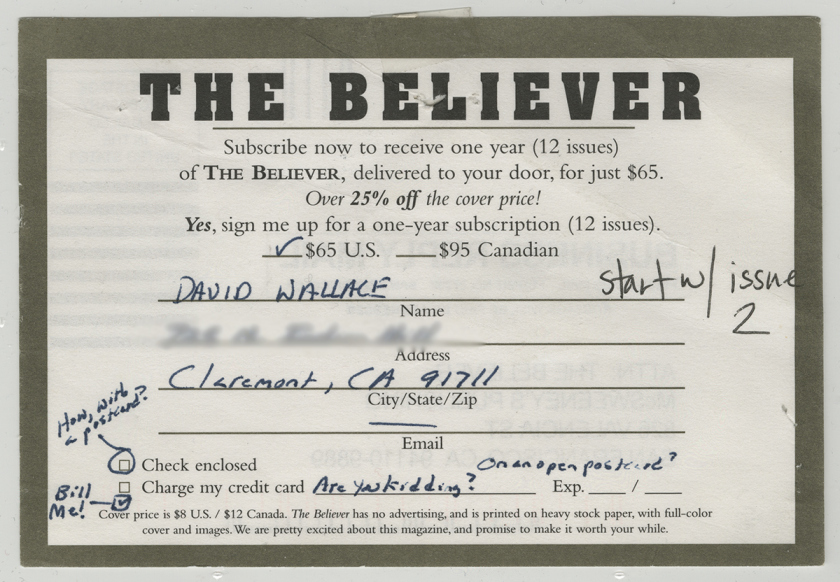

“It’s not about the grade,” I’d say to perturbed students asking me to change theirs: “it’s about what you learned.” No one will care what you got in first-year English Composition; they’ll care if you can write a sentence, a paragraph, a professional, elegant, or moving text. All of this is true, and yet (of course I never told them this) I still remember every grade I earned in every class I took in high school, college, and graduate school. Obsessive? Maybe. But it’s also symptomatic of that same compulsion that drives students to try, by any means, to get professors to bump their grades up at the end of the semester—fear of the “permanent record.” Like Seinfeld’s Elaine, struggling to expunge a black mark from her medical chart, we all fear the reams of documents—or archives of data—that catalogue our every misstep, stumble, failure or faux pas.

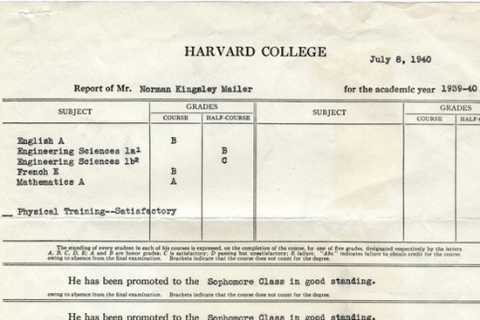

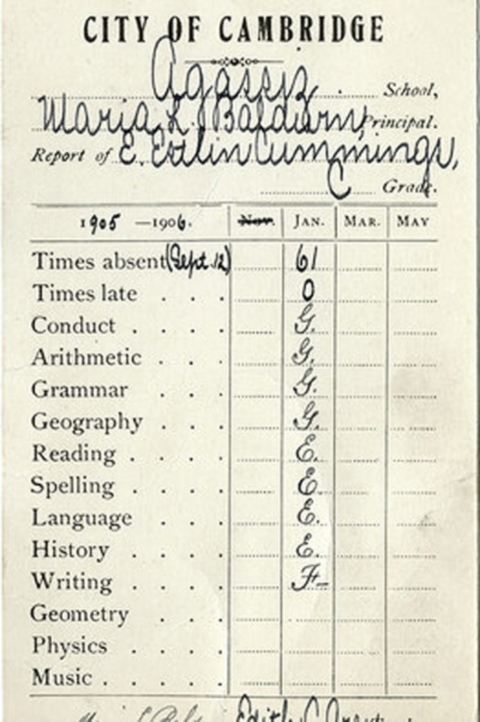

In many cases, this anxiety is justifiable, but as you can see here, the occasional bad mark didn’t stop famed writers Norman Mailer or E.E. Cummings from achieving literary greatness, even if those grades remain, in ink, on record today. See Mailer’s first-year Harvard College report card at the top of the post, academic year 1939–40. The bearish novelist did well, but for the C in his second semester of Engineering Science. Just above, we have Cummings’ report card from what is likely his fifth grade year given his age of 11 at the time. The 1905-06 grading system looks foreign to us now, but the C that Cummings received that year probably did not put him at the top of the class. Nor, I’m sure, did his 61 absences.

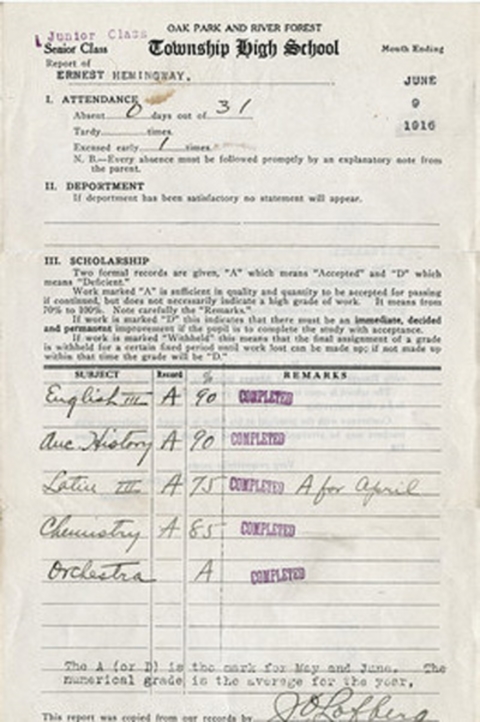

Ernest Hemingway, on the other hand, had little reason to hide the high school report card above, but if you look closely, you’ll see that the column of straight A’s does not mean what we might think. The Oak Park and River Forest Township High School only gave two letter grades, A for “Accepted” and D for “Deficient.” Still, Hemingway’s numerical percentages show his scholarly aptitude, though his 75 in Latin may have haunted him.

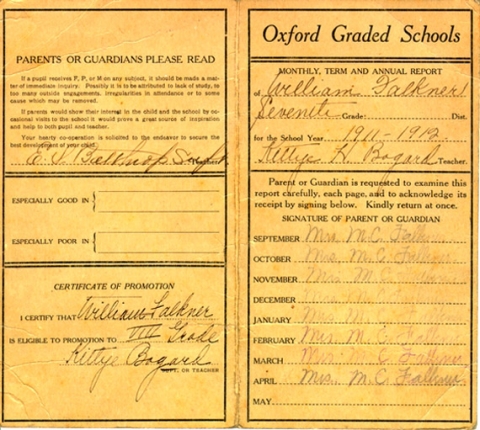

Hemingway’s modernist contemporary William Faulkner, you may know, struggled in school after the fourth grade, and eventually dropped out of high school after the 11th (though his father’s job at Ole Miss meant he could enroll there for the three semesters he attended). The seventh grade report card above does not show us his grades, and Faulkner’s teacher neglected to fill in the “Especially Good In” and “Especially Poor In” boxes. Nevertheless, Faulkner (then William Falkner), did well enough to move up, and his mother signed off on each month of the term but the last.

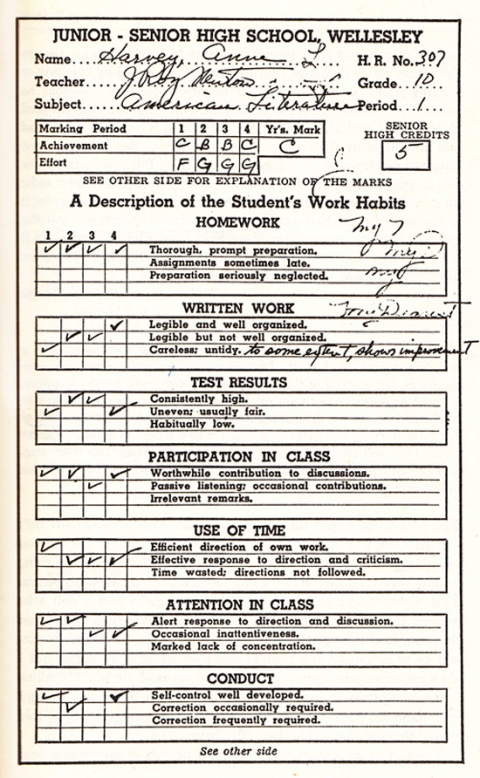

Finally we bring you the report card of Anne Sexton—née Harvey—for a 10th grade American Literature class at the Junior-Senior High School in Wellesley, Massachusetts, from which Sylvia Plath also graduated. As you can see, Sexton received a C in the class, with an F for effort in the first quarter. According to Beth Hinchliffe—a Wellesley native who conducted one of Sexton’s final interviews—the poet remembered the grade. She also remembered her teenage self as “ ‘a pimply, boy-crazy thing’ who was obsessed with flirting.”

Most of these report cards come from collections at the University of Texas’ Harry Ransom Center, a trove of historical and literary documents that, unlike some other archives, I’m very glad keeps permanent records. Anne Sexton’s report card comes to us via the always information-rich Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

Two Childhood Drawings from Poet E.E. Cummings Show the Young Artist’s Playful Seriousness

Anne Sexton, Confessional Poet, Reads “Wanting to Die” in Ominous 1966 Video

How Famous Writers — From J.K. Rowling to William Faulkner — Visually Outlined Their Novels

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.