Read nearly any critical commentary on James Joyce’s Dubliners, his 1914 collection of short stories that chronicle the lives of ordinary Irish residents of the title city, and you’re sure to come across the word “epiphany.” This is not some academic jargon, but the word Joyce himself used to describe the way that each story builds to a shock of recognition—often in the form of painful self-awareness—for key characters. Short-circuiting the typical climax-resolution-dénouement of conventional narrative, Joyce’s epiphanies give his stories a verisimilitude that can still feel very unsettling, given our typical expectations that realist fiction still obey the rules of fiction. Dramatic moments in our lives rarely have neat and tidy endings. But in stories like “Eveline,” “Araby,” “A Little Cloud,” and the collection’s capstone piece, “The Dead,” the often feckless characters find themselves paralyzed in states of existential dread by sudden flashes of self-knowledge, unable to assimilate new and painful insights into their limited perspectives.

That final story (adapted into John Huston’s final film) “elevates the book to the level of the supreme artworks of the 20th century,” writes Mark O’Connell in Slate. O’Connell’s essay commemorates the centenary of Dubliner’s publication this month. Dubliners remains, he writes, a book that “writers of the short story form seem basically resigned to never surpassing.” Written in the author’s early 20s, the stories, as Ulysses would eight years later, “reveal something profound and essential and unrealized about the city and its people”: “Dublin can feel less like a place that James Joyce wrote about than a place that is about James Joyce’s writing.” All of us non-Dubliners can enter the city through Joyce’s exquisite stories, and in an increasing variety of ways, thanks to digital technology. At the top of the post, find a digitized first edition of Dubliners. Just above, we have a reading of “Eveline” by “velvet-voiced” Dubliner Tadhg Hynes, and below, hear Irish actor Jim Norton read “The Sisters.”

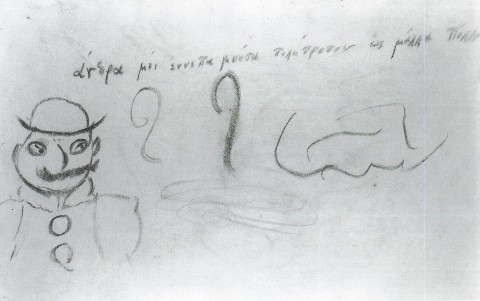

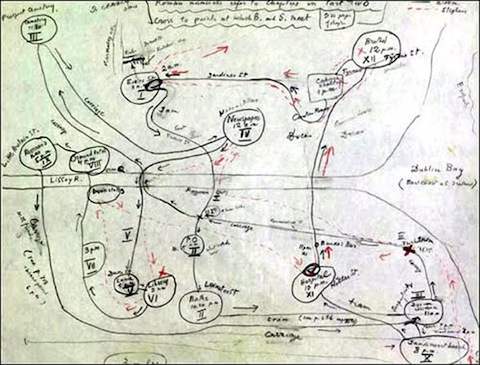

You’ll find many more readings of Dubliners’ stories online, such as this deadpan reading of “Araby” from one of our favorites, Tom O’Bedlam, a Bloomsday reading of “Eveline” by award-winning Irish playwright Miriam Gallagher, and this Librivox collection of readings from various voices. I think Joyce would have very much appreciated the use of technology to keep his work alive into the 21st century. Part of his literary mission—certainly in many of Dubliners’ stories—was to illustrate the stultifying effects of clinging to the past. An eager adopter of new technologies, Joyce in fact brought the first cinema, The Volta, to Dublin in 1909. So it seems fitting that 100 years after the publication of Dubliners, his book receive the multimedia app treatment in the form of Digital Dubliners, a free, “engaging and authoritative edition” of the book designed by Boston College students and featuring “three hundred-odd images, seven hundred or so notes and explanations, two dozen videos, critical essays and hyperlinks, interactive maps sourced from contemporary newspaper, sound, film and photographic archives, with essays, film, recordings, background and expert discussion.” Watch a short promo video for Digital Dubliners below, and download the book on iTunes here.

Finally, you may wish to read the text in a more late-20th-century, and more open, format with this fully searchable “hypertextual, self-referential edition” prepared for Project Gutenberg. Whichever way you read Joyce’s Dubliners, you should, I presume to suggest, read Joyce’s Dubliners. And if you have read these stories before, even “somewhere in the double figures,” as Mark O’Connell has, then you’ll know how richly they reward re-reading, or hearing, or studying along with other readers and lovers of Joyce and a well-worn map of Dublin, or its shimmering touch-screen digital equivalent.

Dubliners also appears in our two collections, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free and 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices.

Related Content:

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

James Joyce’s Dublin Captured in Vintage Photos from 1897 to 1904

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness