May 31, 1889, Walt Whitman’s seventieth birthday, occasioned a celebration of the poet in his hometown of Camden, New Jersey, with a several course dinner called “The Feast of Reason” followed by a program called “The Flow of Soul,” a succession of testimonial speeches and readings by prominent politicians and a few minor literary figures. Whitman himself was in ill health, but he managed to attend during dessert, deliver a brief response, then stay for over two hours afterward (see the event’s original program, with menu, here). While the event itself, writes Ed Folsom in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, was intended as a “local celebration of Camden’s most famous personality,” the occasion prompted admirers worldwide to send birthday wishes by wire and letter. Some of the famous literary figures who wrote included John Addington Symonds, William Dean Howells, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Mark Twain.

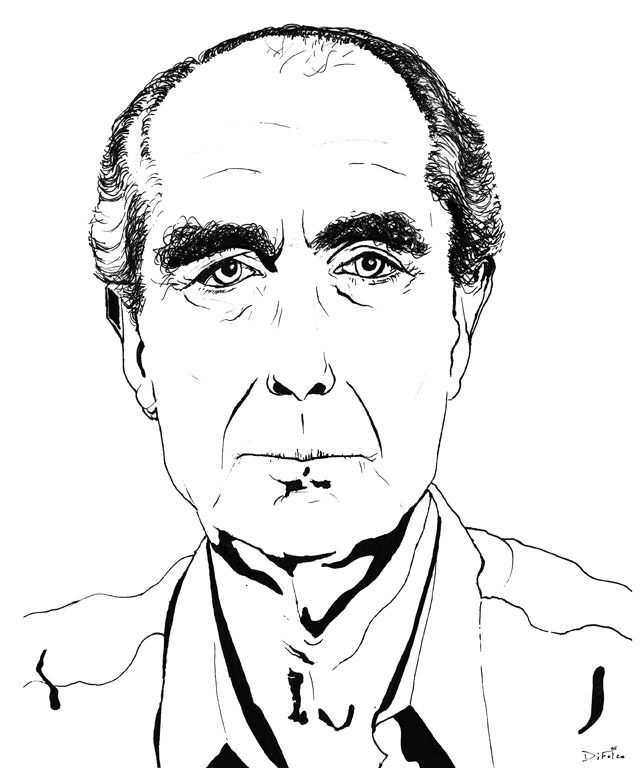

Twain’s letter (first page above) is not only a deeply heartfelt appreciation of the greatest living American poet, it is also, as Letters of Note puts it, “a love letter to human endeavor.” Twain enumerates with awe the astounding technological advances Whitman has witnessed in his lifetime, from steam power to photography to electric light. The letter is characteristic of the optimism of the age—so perfectly captured a little over a decade later in Henry Adams’ memoir chapter “The Dynamo and the Virgin.” Twain, hardly a religious man, evinces an almost rapturous faith in progress, concluding with a Biblical allusion and a somewhat obscure reference to an apocalyptic figure—“him for whom the earth was made”—who would appear in thirty years time. One can’t help but think, in hindsight, of Yeats’ 1919 occult meditation on the loss of that Victorian certainty in “The Second Coming.” As Marc L. Roark observes at The Literary Table, “Twain was correct — thirty years from the letter would see technology like the world never knew. Unfortunately, that technology was that of war.”

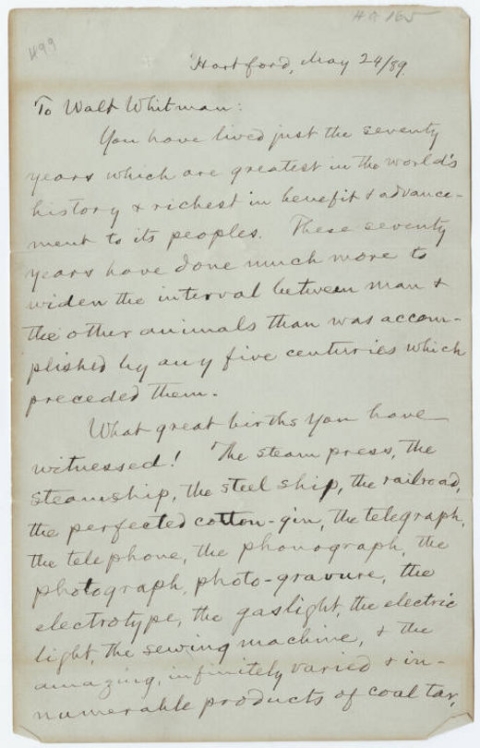

Hartford, May 24/89

To Walt Whitman:

You have lived just the seventy years which are greatest in the world’s history & richest in benefit & advancement to its peoples. These seventy years have done much more to widen the interval between man & the other animals than was accomplished by any five centuries which preceded them.

What great births you have witnessed! The steam press, the steamship, the steel ship, the railroad, the perfected cotton-gin, the telegraph, the phonograph, the photograph, photo-gravure, the electrotype, the gaslight, the electric light, the sewing machine, & the amazing, infinitely varied & innumerable products of coal tar, those latest & strangest marvels of a marvelous age. And you have seen even greater births than these; for you have seen the application of anesthesia to surgery-practice, whereby the ancient dominion of pain, which began with the first created life, came to an end in this earth forever; you have seen the slave set free, you have seen the monarchy banished from France, & reduced in England to a machine which makes an imposing show of diligence & attention to business, but isn’t connected with the works. Yes, you have indeed seen much — but tarry yet a while, for the greatest is yet to come. Wait thirty years, & then look out over the earth! You shall see marvels upon marvels added to these whose nativity you have witnessed; & conspicuous above them you shall see their formidable Result — Man at almost his full stature at last! — & still growing, visibly growing while you look. In that day, who that hath a throne, or a gilded privilege not attainable by his neighbor, let him procure his slippers & get ready to dance, for there is going to be music. Abide, & see these things! Thirty of us who honor & love you, offer the opportunity. We have among us 600 years, good & sound, left in the bank of life. Take 30 of them — the richest birth-day gift ever offered to poet in this world — & sit down & wait. Wait till you see that great figure appear, & catch the far glint of the sun upon his banner; then you may depart satisfied, as knowing you have seen him for whom the earth was made, & that he will proclaim that human wheat is worth more than human tares, & proceed to organize human values on that basis.

Mark Twain

See Letters of Note for the remaining images of Twain’s letter. You can peruse all of the speeches, letters, and telegrams addressed to Whitman on his 70th birthday in the collection Camden’s Compliment to Walt Whitman, published that same year.

For many more fascinating historical letters, be sure to check out Letters of Note’s new book, Letters of Note: Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience.

Related Content:

Hear Walt Whitman (Maybe) Reading the First Four Lines of His Poem, “America” (1890)

Mark Twain Writes a “Gushing,” “Self-Deprecating” Wedding Announcement to His Family (1869)

Mark Twain Drafts the Ultimate Letter of Complaint (1905)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.